March 19, 2019; Washington Post

Between 2000 and 2013, Washington, DC experienced the greatest “intensity of gentrification” of any US city, according to a study released Tuesday by the nonprofit National Community Reinvestment Coalition (NCRC), reports Katherine Shaver in the Washington Post. NCRC consists of about 600 community-based member organizations. NCRC undertook the study because it was demanded by its members, who “raised concerns about gentrification, displacement and transformations in their communities.” As the authors of the study—Jason Richardson, Bruce Mitchell and Juan Franco—put it, “We wanted to better understand where gentrification and displacement was occurring, and how to measure and monitor it.”

Among the findings that stand out are the following:

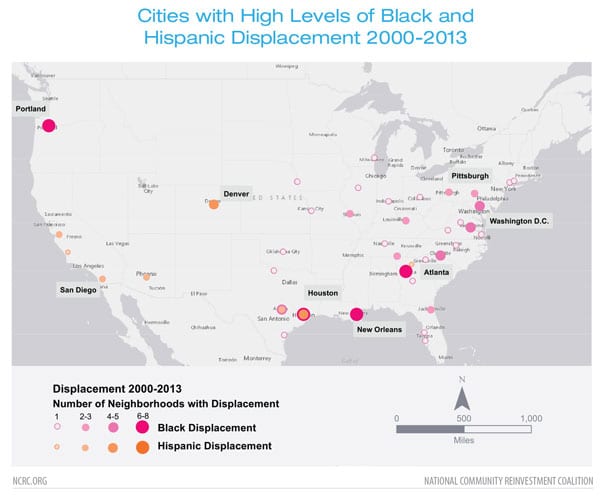

- Displacement of Black and [Latinx] residents accompanied gentrification in many places and impacted at least 135,000 people in our study period. In Washington, DC, 20,000 black residents were displaced, and in Portland, Oregon, 13 percent of the Black community was displaced over the decade.

- Seven cities accounted for nearly half of the gentrification nationally: New York City, Los Angeles, D.C., Philadelphia, Baltimore, San Diego, and Chicago.

- 79 percent of gentrifying tracts are within cities with one million or more residents.

The displacement numbers seem low, but the authors used fairly narrow definitions of gentrification and displacement. A neighborhood was said to have gentrified if: a) before 2000, it was in the 40th income percentile or below, b) by 2013, it was in the 60th income percentile or above and actual household incomes had risen; and c) education levels had gone up. Displacement was said to occur within those neighborhoods if between 2000 and 2010 (the two census years) there was a five-percent or greater decline in the number of Black or Latinx residents. Overall, the study found that 110,935 Black residents were displaced nationwide through gentrification in 187 census tracts between 2000 and 2010, while 24,374 Latinx residents were displaced in 45 census tracts in that same decade.

Nationally, Richardson, Mitchell and Franco indicate that 90.7 percent, or 67,153 census tracts are urban, of which 16.7 percent or 11,196 tracts were poor enough in 2000 so that gentrification was possible (you can’t gentrify already wealthy Beverly Hills, for example). Of these, a total of 1,049 census tracts did increase in economic status (i.e., gentrify), with widespread displacement occurring in 232, or 22 percent, of the gentrified tracts.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

It would surprise few residents of the nation’s capital to see their city rated as having experienced the most intense gentrification. “You feel it and you see it,” observes Jesse Van Tol, chief executive of NCRC. “It’s the visibility and the pace of it.”

“Many residents,” notes Shaver, “can rattle off the DC neighborhoods that have undergone rapid economic change, including Petworth, Mount Pleasant, Brookland, and the U and 14th street corridors.”

The study also identifies remedies that can enable nonprofits and neighborhood groups to improve in terms of living conditions while minimizing displacement. Richardson, Mitchell, and Franco write that there are “several ways in which local stakeholders can promote revitalization to benefit the broader community.” These include:

partnerships between banks and community-based organizations to encourage equitable development; limited-equity co-ops and community land trusts; providing existing tenants with the right of first refusal in apartment conversions coupled with low-income and first-time buyer financing programs; inclusionary zoning regulations; and split tax rates for the incumbent residents of gentrifying neighborhoods. Additionally, HUD’s Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing (AFFH) process provides an opportunity for community groups to engage with municipal leadership in the planning process. AFFH provides a mechanism for identifying areas that are vulnerable to, or may be in the early stages of, gentrification. Community groups can then work to develop strategies to avoid displacement of incumbent residents by attracting investment and providing affordable housing.

In an essay accompanying the study, Sabiyha Prince of Empower DC highlights the importance of community activism to effectively address these challenges. Gentrification, notes Prince a “policy-driven process that begins with targeting low-income, urban communities for discrimination and neglect and ends with ‘improvements’ that exacerbate vulnerabilities that culminate in displacement.” To respond, Prince adds, requires working ‘with directly affected residents in order to build their capacity for leadership by harnessing their collective power and fostering self-confidence.”—Steve Dubb