This article is from the Nonprofit Quarterly’s winter 2017 edition, “Advancing Critical Conversations: How to Get There from Here.”

Dear Nonprofit Whisperer,

I am a new board member of a thirtyish-year-old, struggling nonprofit. All but one member (the sole employee on the board) believe that our executive director is God’s gift to the organization. My province is governance, and I would like to introduce the issue of ED succession planning to the board. Our ED is a nonvoting ex officio board member and should (in my view) be a major player in designing an approach, a policy, and, ideally, a procedure vis-à-vis this issue.

What is the best way for me to introduce this idea to the board without making the ED feel threatened and/or most of the board feel it’s a waste of time and something to be delayed until we aren’t so overwhelmed? Truth is, what the board is overwhelmed by is its habit of micromanaging, which frequently leads to contradictions apropos of even the smallest decision made by the ED.

Worried

Dear Worried,

It is hard to join a board with an entrenched culture, and talking about succession planning can definitely be a thorny issue. I have sat on a number of boards over the last thirty years, and the short answer to your question is: start with a sensible request for procedures for unplanned absence (emergency) and planned absence (family leave) to be established. Such procedures are typically part of any succession plan and help to ease the topic into the conversation. (And yes, the ED should take the first stab at designing the procedures.) Hopefully, awareness, knowledge, and trust will develop as that work happens, enabling the next steps toward succession planning for permanent departures.

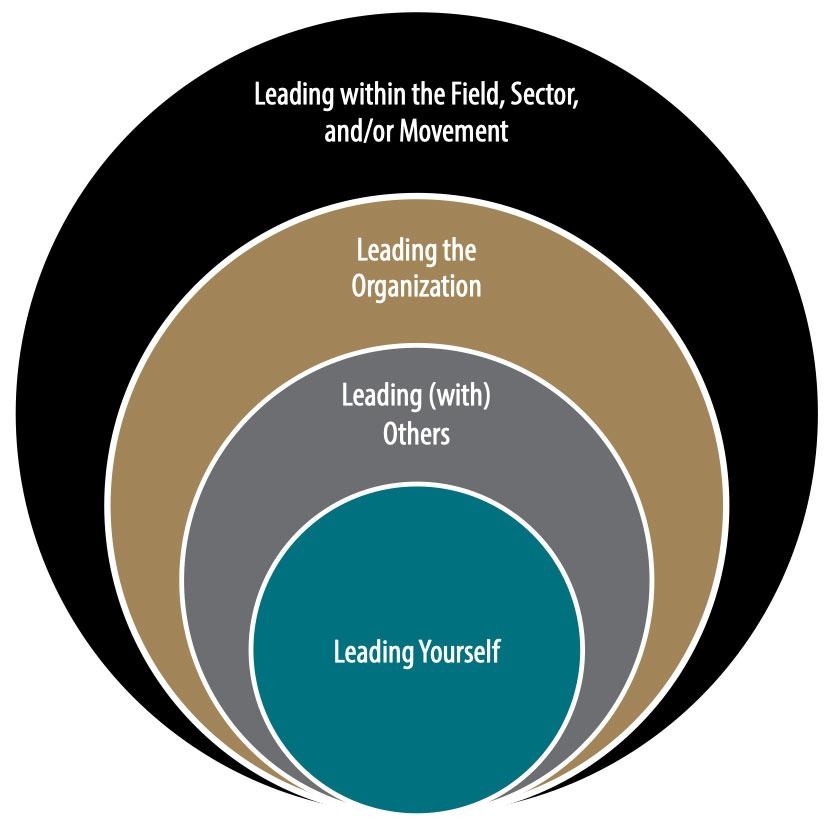

In truth, fewer than 50 percent of nonprofits have succession plans, because succession is such a difficult topic. Among people who work in the field of succession planning, the conversation has shifted toward building a sustainable organization as the best way to ensure a sound transition. Succession planning is now treated as a piece of that process, not the be-all and end-all. Which brings us to the long answer: you can help to grow sustainability by supporting the board in developing so that it is more strategic and less involved in micromanaging. That is the long game, and it will help build the organization in such a way that the topic of succession will naturally be entwined with conversations about staff development and distributed leadership.

Keep in mind that no two boards are alike, and when new to a board it can be a good idea to take stock for the first few meetings (or first six months) and analyze the collective culture of the board and where and how you can make a significant contribution (unless there is something egregious needing immediate action). It sounds as though you have the capacity to pinpoint areas for needed organizational growth and development, but other board members may have to be brought along to recognize the same need for change. So, before tackling other issues, consider working on enriching the soil for governance by taking a few small process steps that will help the board get out of its micromanagement habit. Shifting this behavior would be a major contribution and set the scene for future growth and for tackling more strategic issues.

Put another way, I have found that no matter how much perspective, knowledge, or how many skills I might bring when I join a board, boards are in essence minisystems, and systems are best influenced by applying the right lever at the right time. Typically, that lever is a “precondition,” or step, for bigger change, and it often involves procedural tweaks. Once the smaller changes take hold (in the case of your board, this would be less micromanagement), then the ability to have more generative, strategic conversation grows, and the board can work to tackle important stuff—like succession planning—within a strengthened boardroom context. Governance guru Bill Ryan describes the importance of the board-meeting agenda as one of those levers: simply making time for strategic conversations and not having pro forma committee reports take up the entire meeting can be a game changer. Using inquiry—leading with questions—versus answers and prescriptions can also create a change in board culture, as a question leads to a conversation and can create a habit of critical thinking.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

In other words, you may want to back into the succession planning conversation by simply asking some questions. You could start with questions about why the board is micromanaging (when you see this habit playing out in real time). You could use your governance role to ask other board members what they feel they need to learn in order to practice good governance—or you could introduce an assessment tool for them to fill out that points out what good governance looks like (succession planning should be on the checklist). When you have gained some cachet with the board, you can also help members lean into a conversation about overall sustainability by starting with the role governance plays (a role that involves building a healthy pipeline for new, diverse, skilled board members).

Once the board has taken care of its own succession planning, it will become quite natural to have this conversation at the staff level. If you are concerned that handling the conversation at both board and staff levels would consume a three- or six-year tenure on the board, you could simply lead with (or layer in) a conversation about whether the organization has enough bench strength at the staff level or is overly reliant on one leader—and if the latter is the case, how the board can help get to more sustainability in terms of its human capital.

Dear Nonprofit Whisperer,

Most of us know there is a wide range of boards—some more effective and healthy than others. But the majority of boards do not understand the need for adequate time lines for leadership transition and are more likely than not to rush a nonprofit leadership or transition solution in order to check the issue off their list. My question is, how can an organization/ED get the board to understand that a longer time line is critical?

Concerned Board Member

Dear Concerned,

There is the saying “go slow to go fast.” A leader I spoke with recently told me that for the second time in her working life, she had panicked about hiring a manager and had rushed it through—an expensive mistake, as time spent hiring, onboarding, and letting go a new high-level staff person within three months is resource intensive and disruptive. For even a small nonprofit, a board should plan on at least six to eight months from the time an executive director announces his or her departure to the time when a new leader arrives. For larger, complex organizations, plan on a year or so.

The Nonprofit Quarterly has been publishing articles on executive transition for many years, and I am not going to repeat the steps of a good executive transition here except to say that a board should never rush to a search and hire, as these are actually the middle steps of a sound executive transition process.1 A board’s first step should be to assess where the organization is now and where it thinks it will be in five years, and then create a vision statement around that. A “transition” or “search” committee can then develop a leadership profile built around the skills and attributes required to move the organization to its five-year vision—not based on the characteristics of a great departing director or swinging the pendulum to ensure the weaknesses of a former ED are corrected but rather on the organization’s current and near-future vision, strategy, and needs being matched by the right leader with the right skills and attributes.

It is recommended that, if the organization has the resources, it hire an executive-transition consultant to support the board through the process. If the organization has some fires to put out (poor financial status, for example), consider an interim executive director to help steady the helm and make it a more attractive option for potential leaders. Hiring an interim—making sure that he or she is a very competent and knowledgeable one—allows a board the space and time to ensure a good hiring process for its next leader.

Note

- See, for example, Tom Adams, “Departing? Arriving? Surviving and Thriving: Lessons for Seasoned and New Executives,” Nonprofit Quarterly 9, no. 4 (Winter 2002); the editors, “Letting Go: A Leadership Challenge,” July 28, 2017; and Jeanne Bell and Tom Adams, “Nonprofit Leadership Transitions and Organizational Sustainability: An Updated Approach that Changes the Landscape,” webinar, March 22, 2017.