“I moved out of Boston because the cost of living in the city was not sustainable on my 10-month stipend [~$28,000],” said Jordan Pickard, a PhD candidate in English at Boston University. “The city that I live in now is more affordable. But because I’m now in zone 4 of the commuter rail, I’d have to pay $1,000 per semester for a pass—which is a huge strain, especially since it has to be paid in a lump sum. I can’t afford to live in walking distance of my work, and I also can’t afford to commute. Something has got to give.”

Pickard was one of 600 PhD signatories, in addition to hundreds of undergraduate, masters, and faculty supporters, who signed a petition addressed to administrators at Boston University (BU) requesting the inclusion of graduate workers in the university’s Massachusetts Bay Transit Authority (MBTA) discount program.

All faculty and staff workers at BU are entitled to a 50 percent subsidy on MBTA passes, which was framed as an effort to create a greener campus and alleviate the financial burdens of commuting. But graduate student workers at BU are excluded from this program—many of them, like Pickard, are often forced to live far from their workplace due to high rents around the university and modest graduate stipends. Like many “progressive” policies in the higher education sector and elsewhere, BU’s sustainability policy leaves out many in need of help.

The sense of frustration and powerlessness felt by grad workers like Pickard has a clear cause: the lack of a collective bargaining agreement between BU and its grad workers has enabled the university to routinely exclude them from benefits provided to other workers on campus, while expecting them to perform the same type of labor as faculty in terms of both teaching and research.

In response, the newly relaunched Boston University Graduate Workers Union (BUGWU) has taken up this issue. The university initially ignored the petition when it was electronically delivered in May. Its failure to acknowledge graduate student worker demands prompted an in-person action on June 9th: over 30 BU grad workers hand delivered the petition to the Office of the President, pressuring the administration to formally acknowledge that they had indeed received the petition and promise to respond before the start of the fall semester.

In late July, citing BUGWU’s efforts, BU administrators claimed that they “determined that rather than providing increased MBTA subsidies, the best way to support BU PhD students currently receiving stipend funding would be to increase stipends by an additional 1.5 percent beyond the 2.5 percent planned for the 2022-23 academic year.” Although this stipend increase does not fully address the financial difficulties BU’s grad workers experience, it amounts to well over one million dollars won—after just a few months of organizing—for over 2,500 of the lowest-paid workers at a large private university in one of the most expensive cities in the country. There is also a broader story here about how groups of workers can fight simultaneously for equity and climate policy, while also building an organization that empowers labor.

Transit Equity and Climate Policy

Undoubtedly, MBTA, known as the “T,” is a vital part of the lives of many Bostonians. “Living in Boston, a T pass is not a perk. It’s a necessity,” said Corrine Vietorisz, a Biology PhD worker. “I used to work at BU as a lab technician and only had to pay $40 per month for my MBTA pass year-round. Now, I am a PhD student and making much less money than I was while as a technician—yet, I have to pay much more for my pass than when I was a tech. In both roles, I’ve been helping do the research that makes BU an R1 university, but receiving much different benefits.” Transit costs fall particularly heavily on workers in the laboratory sciences, whose service requirements require them to commute to campus more frequently.

Transit equity and justice are also particularly important for those who do, or can, not drive—including people with chronic disabilities such as epilepsy, people whose medical conditions require the use of medications that render them unable to drive, and people with temporary disabilities. Such individuals are significantly disadvantaged by the university’s unwillingness to subsidize transit costs. As Samatha Hall, a PhD worker in environmental health, wrote, “When I got in a bike accident with a major concussion this year, I was thankful that public transportation was available as an alternative commute. However, I was limited in my access to public transportation because of cost (I’m on a PhD stipend), and so I walked 30 minutes to the free BU shuttle (doubling my commute time).”

BU’s employee MBTA benefits are set up through MBTA’s Perq for Employers program, which allows employers to order and distribute monthly passes using pretax payroll deductions. The existing infrastructure is perfectly capable of delivering such benefits to all BU employees, including graduate workers. All BU would have to do is order additional passes through Perq and subsidize 50 percent of the cost (45 dollars per commuter per month for the most common LinkPass).

The Perq benefits program demonstrates that public agencies like the MBTA already recognize the value of helping employees commute to work. Working peoples’ reliance on public transit has made such transit a significant issue in local politics in Boston and other cities nationwide. Progressive politicians like Boston’s new mayor, Michelle Wu, responded to this need. In early 2022, Mayor Wu introduced a pilot program that makes three bus lines completely free. The mayor and media outlets like the Boston Globe have consistently characterized the program as a “climate justice” initiative.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

As the climate crisis worsens each year, the effects of the deterioration of underfunded public transportation infrastructure will only accelerate. Indeed, like much public infrastructure in this country, the MBTA is badly in need of repair. The same week BUGWU won the 1.5 percent stipend increase, an MBTA train burst into flames above the Mystic River, forcing one rider to jump and swim to safety. Unions can and must push for public transit subsidies and a just transition to renewable energy. BUGWU’s efforts show that we need not leave all action to politicians; by directing our grassroots union organizing toward subsidizing transit costs, we can do our part outside of election cycles to move climate justice policy forward.

Fighting for transit discounts is therefore simultaneously a labor struggle that could benefit all grad workers at BU, a health struggle that addresses the concerns of people with disabilities and illnesses, and a climate struggle that could reduce dependence on cars in the city. BUGWU’s demand for subsidized passes constitutes part of our mission to bargain for the public good, even before securing a contract. It demonstrates the potential of what unions can do both for the workers they represent and the communities to which they belong.

Building Sustainable Organizations

Issue campaigns, like the MBTA discount campaign, have been instrumental in building new unions. They also belong to a long tradition of unions using specific, concrete, popular issues to agitate workers and build a lasting organization. Grad workers at BU took inspiration from the work of MIT’s Graduate Student Union, which championed the fight for mental health care, Covid relief, racial justice, and international students’ rights after publicly announcing their union in fall 2021.

While many of the signees of the MBTA petition were involved in organizing the union at BU before this particular campaign, the MBTA campaign offered another chance for new members to get involved. The petition was circulated digitally and posted on campus without alerting the university to ongoing unionizing efforts.

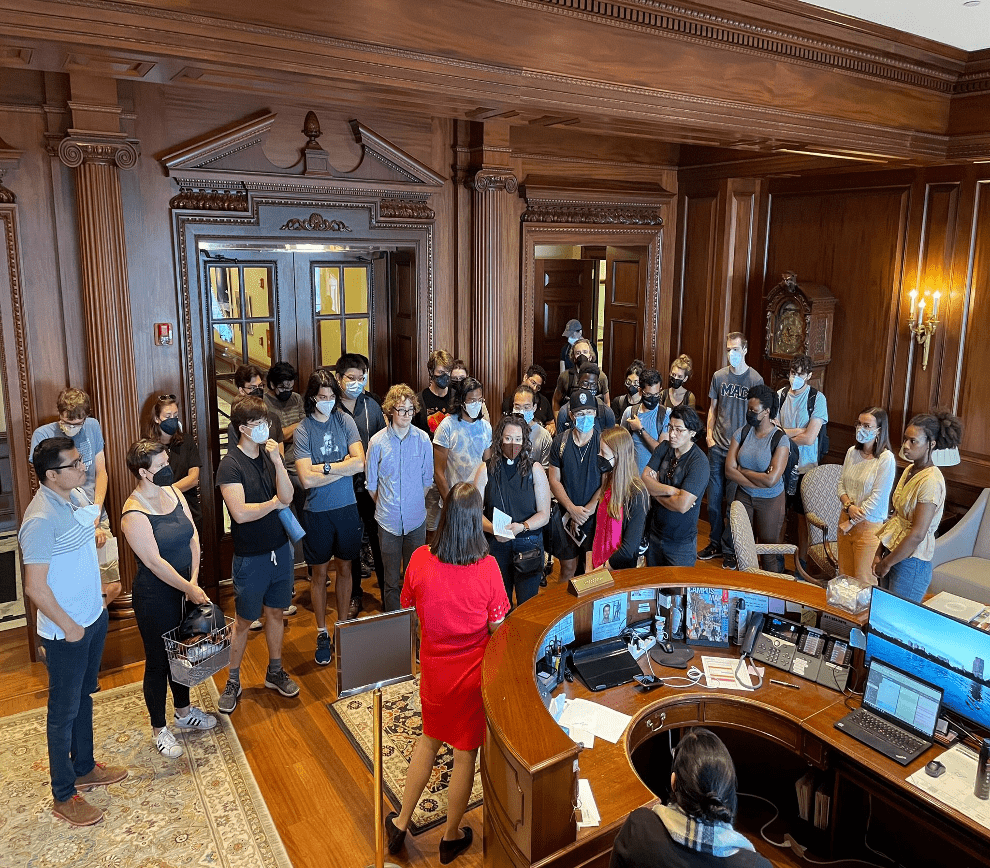

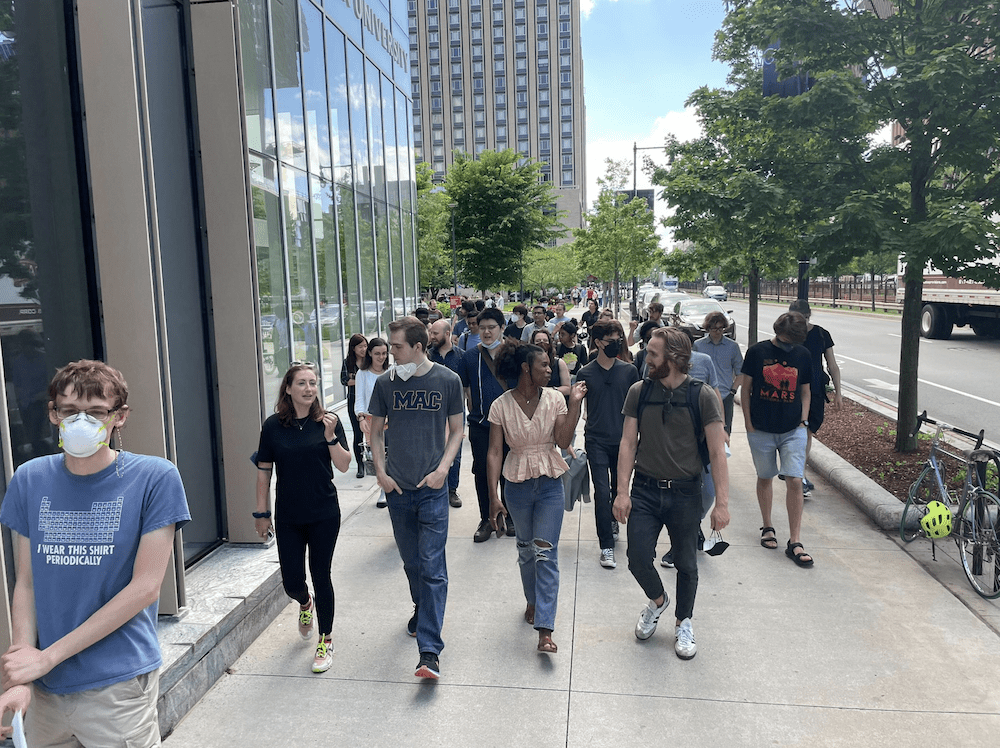

Delivering the petition to university administrators served at least two purposes: to alert the university to the seriousness of our request and workers’ willingness to continue escalation, and to test our union’s ability to organize an in-person action. After organizing digitally for months, many of us met each other for the first time. We walked across campus together, took several elevators up to the mahogany-lined walls of the ninth-floor presidential office, and waited until representatives would meet with us. When they did, we read testimonials, including those from Pickard and Vietorisz quoted above, before demanding a response from the president within two weeks. Feeling the mounting public pressure, the Office of the President responded with an email the day after, promising that BU would look into the matter.

Various departments were already pressuring BU for stipend increases prior to the MBTA discount campaign. Such demands were part of a parallel campaign around salaries meeting rising inflation. Early this year, BUGWU organized formal letters from several departments, including political science, English, theology, education, and counseling psychology, requesting cost-of-living stipend increases. In response, the university promised to look further into the matter.

Throughout late June and into July, we continued emailing the university and began preparing another in-person action. But to everyone’s surprise, BU administrators announced a 1.5 percent raise for all graduate workers instead of transit subsidies, attempting to connect the issue of inadequate stipend support with the MBTA petition.

While certainly a major victory, graduate workers had not requested a raise. Small, pre-contract concessions like these are a form of soft union-busting often used in higher education: both MIT and Princeton instituted preemptive raises last year in response to graduate student organizing. Initial responses to mounting pressure are reframed as magnanimity on the part of the employer, who hopes to instill a sense among workers that a union is not necessary.

A stipend increase of 1.5 percent is not a real raise. For ourselves, our most vulnerable colleagues, and the common good of public transportation in our city, we will continue to demand transit subsidies equal to those of other employees at BU and stipend increases that match the cost of living in Boston (at least $46,918 per annum for a single adult according to MIT’s Living Wage Calculator).

Our campaign shows proof of concept: that organizing works and that unions are integral in securing workers’ demands. With our initial efforts, we have secured raises for thousands of workers and helped build organization and solidarity. We understand that this is a first step and will not compromise on our bold demands for small concessions. If nascent unions focus on winnable issues faced by a majority of workers, establish collective demands which protect the most vulnerable, and build strong organizations with an active membership, victory will follow. First wins may be small and incremental, but they are a sign of things to come and the foundation of a future where we can all thrive.