July 29, 2020; New York Times

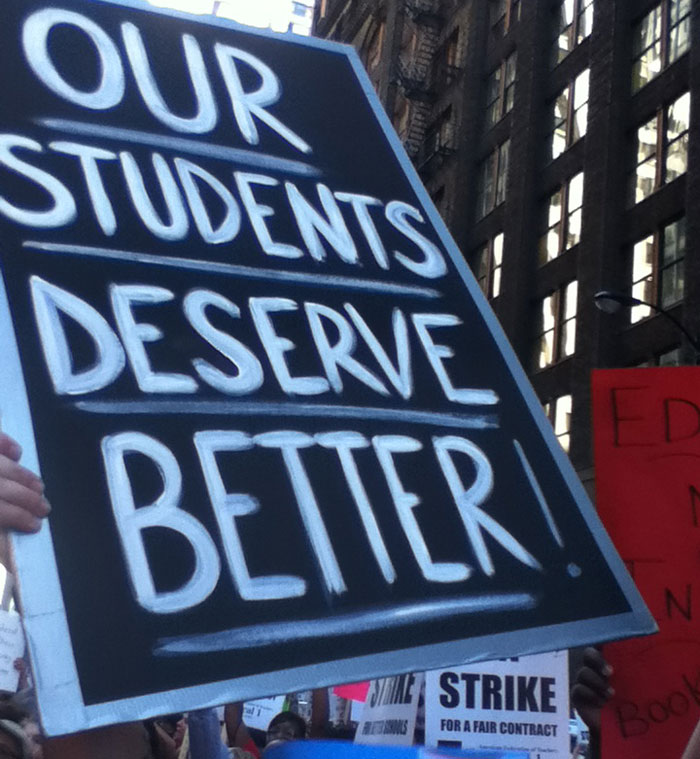

This week, as the start of the school year looms with many open and contested questions on the table, the American Federation of Teachers authorized its chapters to strike—albeit as a last resort—if they are not assured that the conditions for teaching and learning are safe and reasonable. This gives the unions considerable leverage, but it comes at a time of great tension among stakeholders.

The authorization also comes on the heels of significant collaborative action across the country between parents and teachers in the #RedforEd movement, which advocated for higher wages and more school funding among other things. It’s not clear how the situation may affect those connections because, as almost everyone has noted, the situation is not only fraught but chaotic, in that the virus’s course both in localities and in infected individuals remains unpredictable.

Union leaders say that although many teachers stepped into the breach that opened up in March, developing a model for this school year is complicated. The number of competing opinions from elected officials at every level and from parents who often disagree with one another is dizzying. A July poll found that 60 percent of parents supported delaying reopening schools until the virus is under control. Polls show that Black and Latinx families, who have suffered the most from the pandemic, have expressed more concern about returning to school than white parents have, but are also more worried about the academic and social impacts of online learning.

But these opinions vary by all kinds of factors, including geography, even from one community to another.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Pressure from California’s politically powerful teachers’ unions helped push Governor Gavin Newsom (D) to announce guidelines this month that will require many of the state’s districts, covering more than 80 percent of its population, to start school remotely, opening classrooms only once new infections and hospitalizations decline sufficiently. Los Angeles, the nation’s second-largest school district, had already made the decision to start the year online because of soaring infections. Now the union and administrators are engaged in long negotiating sessions via Zoom, with one of the stickiest points of contention being how many hours per day teachers should be required to teach live via video.

In Orange County, Florida, Wendy L. Doromal, president of the Orange County Classroom Teachers Association, called hybrid models especially worrisome. “You can’t keep track of people remotely and in front of you at the same time,” she says.

In New York City, Mike Mulgrew of the United Federation of Teachers in New York City helped draft a plan for onsite—albeit part-time—student attendance at the schools, but he now believes that it is dangerous to reopen without additional resources like air filtration systems and additional medical personnel.

City officials have been caught off guard by the reversal, but the landscape is nothing if not evolutionary—which is, in the end, something the unions want to have acknowledged.—Ruth McCambridge