February 19, 2020; Star Tribune (Minneapolis, MN)

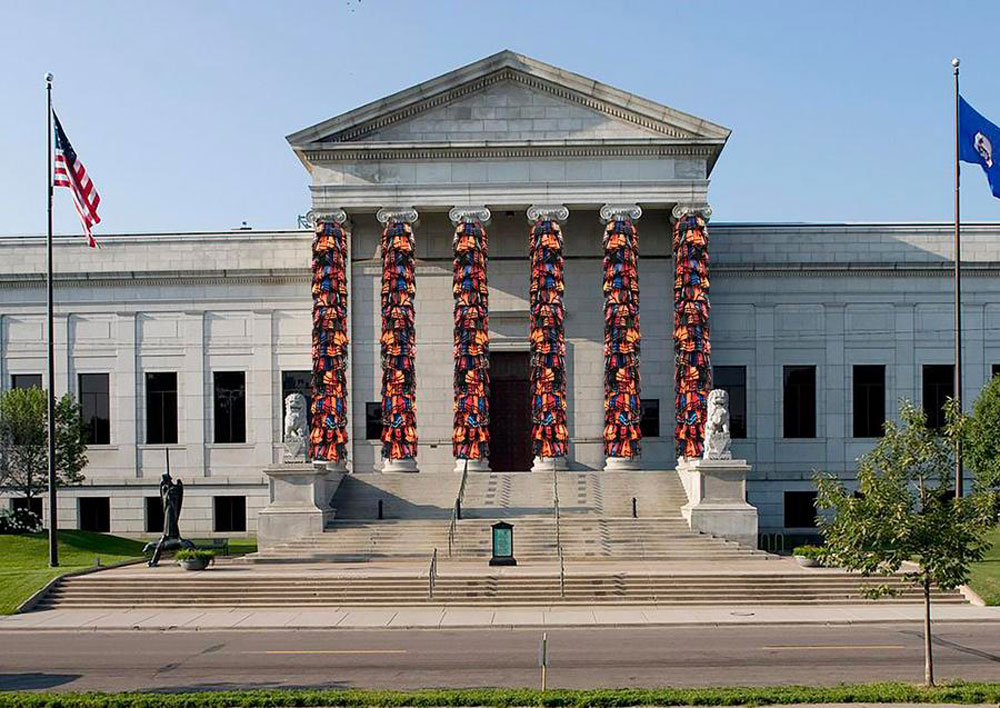

Refugee life jackets adorn the Minneapolis Institute of Art’s exterior pillars, a bright orange and blue reminder to residents that a refugee crisis of almost unimaginable scale is ongoing. The jackets form part of a new exhibition about refugees and migration.

“When Home Won’t Let You Stay: Migration Through Contemporary Art,” an exhibit of which the jackets are only one part, will be at the Minneapolis Institute of Art until the end of May. It’s described as evoking fear, uncertainty, and abandonment. Twenty-one artists from around the world collaborated to make the show, highlighting the global nature of the refugee crisis.

The United Nations reports that over 70 million people were displaced by the end of 2018; over five million of them were displaced by the conflict in Syria. The jackets hung on MIA’s exterior pillars are from Syrians who landed on the Greek island of Lesbos; they were hung by artist Ai Weiwei, a refugee himself.

The exhibit started in Germany in 2016, at the Konzerthaus Berlin. The mayor of Lesbos donated the jackets to Weiwei, who criticized the way Europe handled the crisis; he hung 14,000 of them on the Konzerthaus’s pillars, the same way they hang now at Mia.

The whole show is touring around the US; it started in Boston at the Institute of Contemporary Art, but Minneapolis added some important exhibits. Mia contemporary art director Gabriel Ritter asked Postcommodity, an indigenous interdisciplinary art collective, to contribute a piece, and also commissioned five artists to work together on a piece about the lives of immigrants and refugees in the US.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Nearly sixteen percent of Minneapolis residents were born outside the US, compared to about 13.5 percent for the US as a whole. That’s not the same thing as refugees, of course; Twin Cities estimates that about 13 percent of refugees in the US live in Minnesota, six times their concentration as part of the general US population. The number of refugees accepted into the US has shrunk to practically nothing until President Trump.

Thinking about the refugee crisis in relation to US politics was part of Ritter’s goal. “We vote for people, and the decisions that are made in our name have very real ramifications. Even if you don’t think of yourself as an immigrant, unless you are of Native or Indigenous background, [these are all things] we need to come to terms with,” he said.

NPQ has been following the use of art to draw attention to crises and act as an agent of change. Just a few weeks ago, RAICES Texas installed cages at polling stations for the Iowa primary—and then there’s the prominent role that art played in the overthrow of Ricardo Rosselló in Puerto Rico.

Mia’s former director, Kaywin Feldman, took big steps to make the museum a community space. (Many museums across the US are struggling to figure out how to make their spaces more welcoming and engaging.) Feldman created a Center for Empathy and the Visual Arts and made membership free. She went to lead the National Gallery of Art just a few months ago, and was replaced in January by Dr. Katherine Crawford.

Ritter commented on the fact that exhibits from the migration show had temporarily displaced a popular Greek statue called Doryphoros. “They’re taking the Western colonial core of the museum and displacing it with an Indigenous sculpture,” he said, thereby “decolonizing the museum.”—Erin Rubin