A recent survey by Artist Relief, an emergency initiative by coalition of grantmakers, finds that the coronavirus pandemic is having a devastating financial impact on artists. While artists often struggle financially in even the best of times, and the effort expected the pandemic to have a significant impact on artists, it was shocked by the extent.

Over 50,000 artists applied for a one-time $5,000 grant, of which there are 200; 11,000 of those filled out the survey. Among its most stark findings are:

- 95 percent have lost income due to the pandemic

- 80 percent do not have a recovery plan

- 66 percent cannot access the resources they need to do their work

Clay Lord, Vice President of Strategic Impact at Americans for the Arts, the research partner on the effort, notes, “The fact that so many of them, even in this terrible circumstance, are still producing creative work for their communities—often without getting paid for it—is a testament to the generosity and necessity of artists.”

Americans for the Arts will use the findings to advocate for increased support for creatives from Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act, which Hyperallergic’s Valentina Di Liscia points out has “largely left the arts by the wayside.”

While this is clearly devastating for artists, the damage to the artistic community is also terrible for the country, because what we need now more than ever is a big cultural shift.

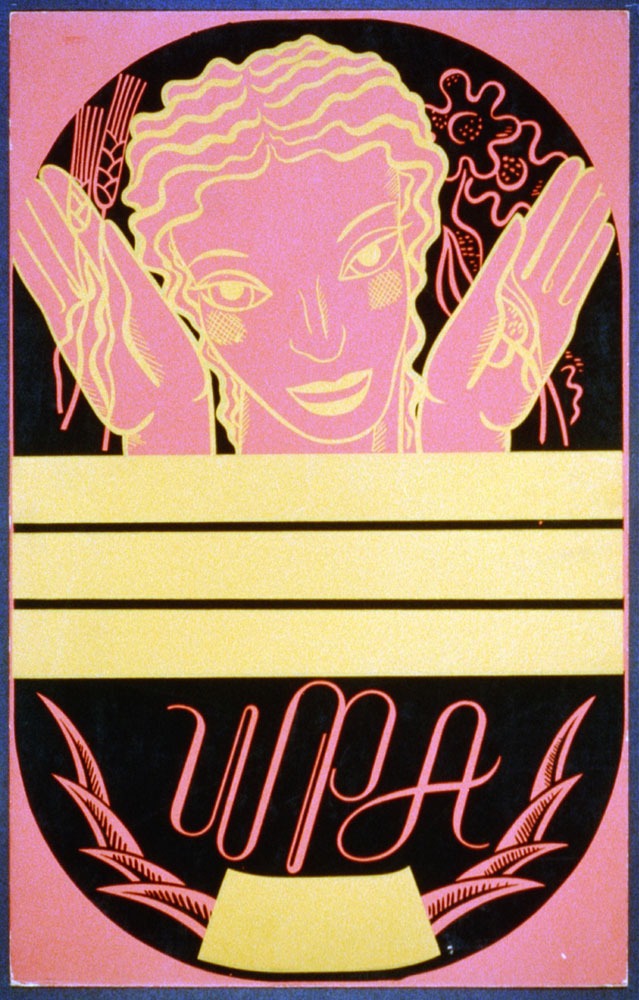

The situation recalls the Works Progress Administration that was launched in 1935 under President Roosevelt to jump-start the economy after the Depression. “During its eight-year existence, the WPA put some 8.5 million people to work (over 11 million were unemployed in 1934) at a cost to the federal government of approximately $11 billion. The agency’s construction projects produced more than 650,000 miles (1,046,000 km) of roads; 125,000 public buildings; 75,000 bridges; 8,000 parks; and 800 airports.” The WPA included the Federal Arts Project, Federal Writers’ Project, and Federal Theater Project. For almost a decade, artists received a paycheck from the government.

The Federal Writers’ Project, for example, employed 6,600 writers, editors, and researchers. A New York Times review of the project notes that, in a time of white supremacy (much like now) it sought to build a national culture on diversity. The project attracted “untested but talented young writers who fanned out across the continent in search of a collective self-portrait of America.” It included Claude McKay, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, Zora Neale Hurston, Studs Terkel. In fact, it was so prolific that “cataloging the output has been a long project.”

At the time of the NYT review, John Cole, director of the Center for the Book at the Library of Congress, who began cataloging it in 1978, was still working on it. He tells NYT, “It’s an amazing collection. The Federal Writers’ Project helped us rediscover our heritage in a more detailed and colorful way than it had ever been described.” John Steinbeck, who relied on the project’s collections for his own work, writes, “The complete set comprises the most comprehensive account of the United States ever got together, and nothing since has even approached it.”

Ralph Ellison’s friend Albert Murray says that Ellison would not have written Invisible Man without it. He recalls that the WPA pulled artists and writers. “It was even more intense than the Harlem Renaissance.”

But, the engine of the WPA program was the Federal Arts Project. “It financed roughly 2,500 murals, 18,800 pieces of sculpture and 108,000 easel works. Thousands of original poster designs were created to advertise local zoos and library book talks or encourage people to get tested for syphilis and report dog bites.”

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

While some may view art as a luxury, the artist’s role is to change the world—to make us feel, so we can think. “True art…is anticipation, anticipation of styles of life, structures of feeling we do not yet have. It gives us a forecast of a world to come.” And we sorely need this now.

Barbara Bernstein, founder of the New Deal Art Registry, an online guide to art from that era, says, “I’m not sure you can get Congress to agree on anything.” And, as Jacobs notes, “President Trump has cast himself as an arts antagonist, at least when it comes to funding. In each of his budget proposals as president, he has called for the elimination of the National Endowment for the Arts and the National Endowment for the Humanities.”

In contrast, in “Germany’s COVID-19 Relief Plan Is the Envy of the Art World,” ArtNet News’ Kate Brown writes,

The United States hammered out a roughly $2.2 trillion rescue package that contained only $300 million specifically earmarked for arts and media causes, and conservative politicians attacked even this paltry amount as wasteful spending. In contrast, Germany announced a federal aid package featuring a whopping €50 billion ($54 billion) to be distributed to freelancers and small businesses, including those in the arts, while the country’s culture minister praised artists as “not only indispensable, but also vital, especially now. Even more assistance came from the city-state of Berlin, which began funneling €5,000 payments to individual freelancers almost instantly with the promise that “there will be enough for everyone.”

Still, some in Germany say it’s not enough. Local organizations are lobbying for a program specifically for artists, one that takes into account the fact that the cancellation of mass events will harm them particularly for the foreseeable future. A popular petition is calling for universal basic income. One petition reads, “Society may be able to do without cultural life for some time. But if it does so for too long, we could end up in a situation with nobody left to revive it.”

Art helped establish Berlin as an economic backbone of the country after the fall of the Berlin Wall. Artists have flocked to Berlin, including from New York City and London. “According to government statistics, the number of Americans living in the German capital has doubled in the last 10 years.” Its local economy owes a lot to a global creative class, “cementing its status as a creative capital.”

New York Assemblywoman Pat Fahy is calling for such a program now. But, the NYT’s Julia Jacobs doesn’t think it’ll happen. She writes, “There is talk again in some circles of fashioning additional federal help for artists as the pandemic wreaks havoc on their livelihoods….But few defenders of the arts are optimistic that a program as sprawling and generous as the New Deal initiative could happen now.”

But, plans for national programs to reopen and jumpstart the economy are already in the works. NPR reported this week on a national plan proposed by a bipartisan group of former health officials to conduct the testing and contact tracing needed for the US economy to reopen. The plan calls for the White House to hire “180,000 contact-tracers, book blocks of vacant hotel rooms so Americans sick with COVID-19 can self-isolate, and pay sick individuals to stay away from work until they recover.” While it is the most aggressive version of a reopening plan, “given its backing from high-ranking health officials spanning the last three presidencies, it could also prove to be the most viable.”

Further, the deteriorating state of our national infrastructure has been bemoaned for some time. The 2017 Infrastructure Report Card, which is released every four years by the American Society of Civil Engineers, gives the US a D+. A 2019 report by the Brookings Institution, Shifting into an era of repair: US infrastructure spending trends, points to a sharp decline in infrastructure, with most of it being done by states now and focusing on operations and maintenance. It recommends a serious investment, especially as the need to adapt to the climate crisis looms.

Perhaps a WPA-style national program that creates a new workforce to respond to coronavirus, addresses our long-term infrastructure needs, and truly supports artists is a strategy around which our sector can mobilize. While many of us look to philanthropy for relief, and foundations highlight their own adaptive efforts, we also need to demand more of our federal government. A cohesive and coherent strategy just might be the ticket—not just for the economy, but for our culture.