January 14, 2016; Forbes

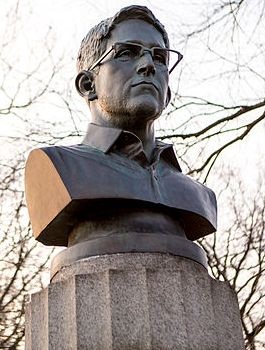

If you didn’t look very closely at the unassuming bust of a young man in glasses on display at the Brooklyn Museum, you may not have realized that the sculpture is not a famous author or scientist, but in fact Edward Snowden, the former CIA employee responsible for one of the largest classified intelligence leaks in the history of the United States. The bust features prominently in the second installment of Agitprop!, a three-part exhibition of political art. The title of the exhibition, which is a combination of the words “agitation” and “propaganda,” is meant to refer to works that utilize art to create political and social change.

As with many contemporary art works, however, the subject of the sculpture is only a small part of the intended aim of the work. This piece originally appeared in Brooklyn’s Fort Greene Park in the early hours of April 6th, 2015, furtively placed atop a preexisting revolutionary war monument from 1908. Within a few hours, NYPD removed the statue and retained it until the artists responsible for the project claimed it. Jeff Greenspan, Andrew Tider, and Doyle Trankina, who conceived of and created the work, were fined $50 for being in the park after dark and had to retrieve the 100-pound, four-foot-tall sculpture from the local precinct. In a statement about the project, the artists titled their work “Prison Ship Martyrs Monument 2.0” and stated that its goal is to “highlight those who sacrifice their safety in the fight against modern-day tyrannies.”

The work’s original installation in the park and subsequent exhibition in the Brooklyn Museum highlights the challenge in establishing political art as a conventional artistic genre. The work is exhibited in a mélange that includes such disparate projects as Soviet-era protests, a series of 1930s photographs of laborers in Mexico, and Jenny Holzer’s Inflammatory Essays series, which appropriates polemical political rhetoric to promote awareness of the subliminal ideologies that infiltrate daily life. The exhibition description on the museum’s website states that its aim is to “connect contemporary art devoted to social change with historic moments in creative activism.”

While it is evident that all the projects presented in this exhibition are expressions of “creative activism,” critics point out that the term “social change” is somewhat vague and does not provide a tangible sense of what can actually be accomplished by political art. Do all of these artists define “activism” in a similar way? If polled, there would certainly be disagreement over the basic usage of the term among the artists featured in the exhibition, and even more so when it came to deconstructing more complex ideological approaches that form the basis for much of the art being presented.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

The bust of Edward Snowden, and the categorization of these works together as “political art,” highlight a deeper question beyond shared definitions of terms or the purported aim of accomplishing social change with art. A commonly argued theme among art historians is that all art is political—it is naïve to believe we can judge a work solely according to purely aesthetic standards devoid of influence from external social factors. From Lenin’s mausoleum to busts of Napoleon and George Washington on display throughout the world, commemorating a controversial and significant historical figure in a public way is nothing new. In the Brooklyn Museum’s exhibition, care has been taken to bring a critical lens to viewing arts’ political impact, and the curators, Saisha Grayson and Catherine J. Morris, selected works that challenge established systems of power.

As is evident from the Snowden bust, when judging a work in which the artist explicitly states that the main purpose of the work is political, it is necessary to consider the trajectory of the piece, not only its final presentation within the confines of a museum exhibition like this one. Exhibiting the bust in the museum, without the contextual elements of its original exhibition in Fort Greene Park, dilutes the political message of the work and threatens to delegitimize its purported aim by divorcing it from its original, socially derived context.

This exhibit, and the story of the Snowden bust, brings another dimension to Susan Raab’s article about public art that was published last month. What does the selection of a public site for the exhibition of a work, rather than a museum, do for the viewer? The Snowden bust in some ways represents the other end of the spectrum from Raab’s characterization of the Highline’s “mainstream” and consumerist-driven model of public art. As consumers of art, the public no longer seeks it out solely in a museum on a rainy afternoon or in a concert hall on a Friday evening. The Brooklyn Museum, in bringing these political works back into the traditional museum space, is attempting to bridge the divide between conventional artistic expression and consumption and the radical spaces in which they were originally conceived. Is the exhibition a successful marriage of the two? You’ll have to see the exhibit and decide for yourself.

As is evident by the Snowden bust—which cost thousands of dollars and took an entire team to clandestinely install in the middle of the night—people are going to create and display whatever art suits their fancy as long as they have the resources to do so. Curators and art historians, in attempting to understand the ever-shifting and intricate world of contemporary art, will continue to attempt to distill the essential works and establish narrative patterns. As consumers of art, we need to know what we want and be aware of what we’re consuming in order to judge it effectively.—Sophie Lewis