July 20, 2018; The Conversation and New York Times, “Opinion”

The struggle over government policy is often as much a struggle between competing “frames” as it is about facts; if a rose is not a rose, it will not smell as sweet. As nonprofits that serve the needs of the poor and advocate for their causes have worked to reframe their efforts to broaden political support, their opponents are taking countermeasures to redirect the public’s focus from “need” to “merit.” But this, of course, is nothing new. The narrative about the deserving and the undeserving poor is older than the sector itself.

Earlier this month, the president’s Council of Economic Advisers declared victory in the nation’s long war on poverty. Decades of effort have apparently gotten us to the promised land. Programs whose effectiveness had been challenged had actually done their job. With that problem solved—what was that United Nations Special Rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights talking about?—the CEA directed our attention to another problem in need of immediate attention: With poverty behind us, we now need to address the many lazy people who just will not work and are taking resources from the “good” people who do. In their report to the president, they noted:

- “Self-sufficiency has been declining in recent decades while material hardship has fallen, motivating a renewed focus on building self-sufficiency via work requirements.”

- An “alternative solution of increasing positive incentives for work (for example, by increasing the Earned Income Tax Credit) could exacerbate already-high implicit taxes on low-skill part-time workers.”

- “Evidence suggests that welfare programs that require work in return for benefits increase adult employment and may improve children’s outcomes.”

- “Today, many non-disabled working-age adults do not regularly work, particularly those living in low-income households. Such non-working adults may miss important pecuniary and non-pecuniary benefits for themselves and their households and can become reliant on welfare programs.”

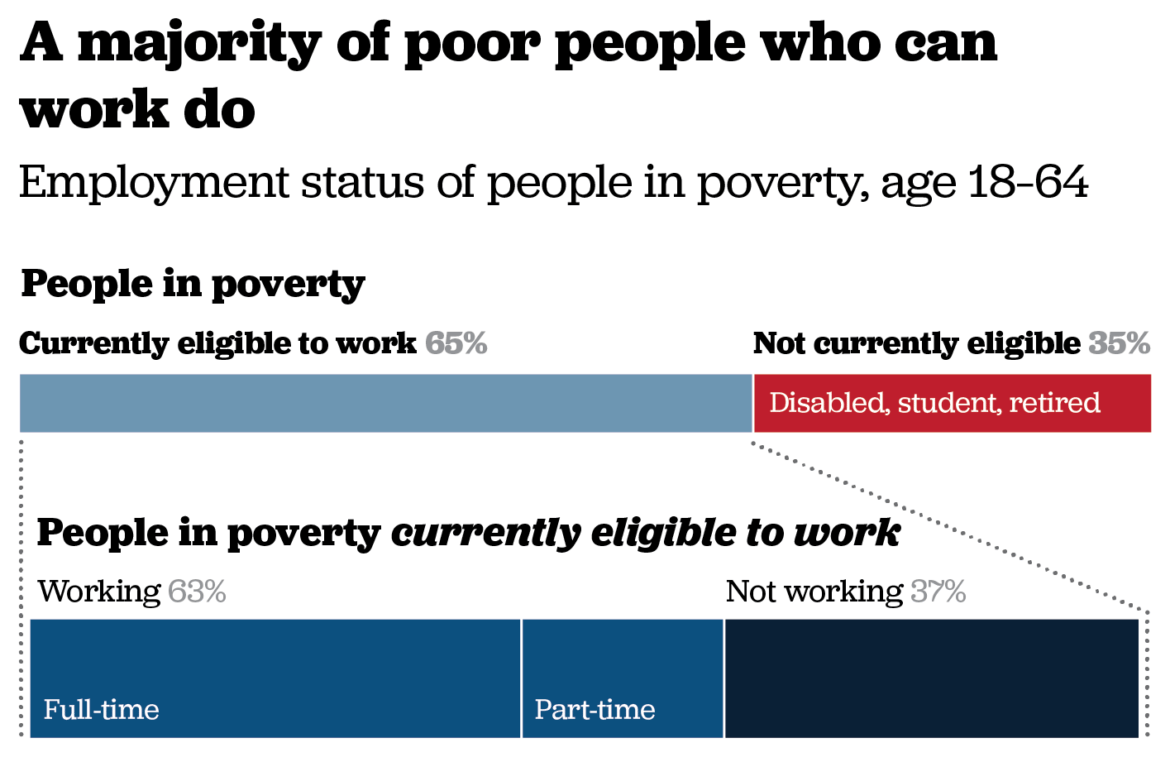

The CEA’s approach is more emotional than factual. It excludes the elderly and the young who make up many of those in economic distress and focuses attention on the less sympathetic image of those who can work but won’t. It frames the issue of poverty as being the fault of the poor and not of the larger system.

According to Robert Fisher writing for The Conversation, the administration’s approach “identifies certain categories of poor as more deserving of assistance because they are victims of circumstance. These include children, widows, the disabled and workers who have lost a job. Other individuals who are perceived to have made bad choices—such as school dropouts, people with criminal backgrounds or drug users—may be less likely to receive sympathetic treatment in these discussions. The path to poverty is important, but likely shows that most individuals suffered earlier circumstances that contributed to the outcome.”

The picture it paints ignores reality: “Among the working-age poor in the US (ages 18 to 64), approximately 35 percent are not eligible to work, meaning they are disabled, a student or retired. Among the poor who are eligible to work, fully 63 percent do so.”

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Fisher also observed that, once poor, because of concentration and isolation, it’s more likely your children will also be poor. Being poor, he writes, “limits the odds that someone can escape poverty. Individuals living in poverty or belonging to families in poverty often work but still have limited resources—in regard to employment, housing, health care, education and child care, just to name a few domains. If a family is surrounded by other households also struggling with poverty, this further exacerbates their circumstances. It’s akin to being a weak swimmer in a pool surrounded by other weak swimmers. The potential for assistance and benefit from those around you further limits your chances of success.”

In an NPQ article from this spring, Debby Warren, recognizing the challenge of overcoming this negative framing of poverty, describes how nonprofits and advocates work to change how they communicate these issues and change how the public looks at efforts to help those living in poverty. To counter the deserving/undeserving narrative, they are moving away from merely presenting facts that justify the “safety net” to “values-based messaging” and “the power of stories.”

Framing may be a powerful weapon in the public arena, but as Warren asks, “How powerful will it be?” In a recent column run in the New York Times, Nobel Prize winning Economist Paul Krugman, prompted by the CEA’s report, suggests that the challenge has moved from justifying the needs of low-income people to validating the role and effectiveness of government itself. Referencing the economists and political leaders who focus on the undeserving poor, he writes,

What motivates these elites is ideology. Their political identities, not to mention their careers, are wrapped up in the notion that more government is always bad. So, they oppose programs that help the poor partly out of a general hostility toward “takers,” but also because they hate the idea of government helping anyone.

If Krugman is correct, then our message must transcend messaging about the humanity of low-income people and those who work with them to improve their and their communities’ straits. The nonprofit community also needs to communicate loudly and effectively the role government ought to play. In this time of cynicism, this will not be easy to do, but if governments are to do the jobs only they can, they’ll need all the encouragement they can get.—Martin Levine