Click here to download this article as it appears in the magazine, with accompanying artwork.

Editors’ Note: This article is from the Winter 2021 issue of the Nonprofit Quarterly, “We Thrive: Health for Justice, Justice for Health,” and was excerpted from Main Street: How a City’s Heart Connects Us All by Mindy Thompson Fullilove (New Village Press, 2020), with permission. It contains minor edits for publication here.

In 1979, I was selected by the American Psychiatric Association for a fellowship program that supported minority residents. Dr. Jeanne Spurlock and her team introduced us to a network of accomplished minority psychiatrists, financed our attendance at association meetings, and provided each of us with a stipend that we could use to create projects in our own training programs.

As a black resident in an all-white hospital, I found this experience liberating. Much of what I was learning in my residency had to do with the internal world of the patient. I didn’t know what to do regarding racism and other forces I knew existed outside the individual’s realm. The people I met through the fellowship—Charles Pinderhughes, Ezra Griffith, Bruce Ballard, Carl Bell, Altha Stewart, Joyce Kobayashi, Earline Houston, and many others—helped me to articulate the relationship between the internal and the external in people’s lives and to manage the dilemma of seeing this complex picture when others in my program did not.

Many of those I met at APA offered useful advice, but one piece stands out. At the time of the 1982 convention in Toronto, I was writing a paper on the meanings of skin color in two short stories by Jessie Redmon Fauset, a major figure in the 1920s Harlem Renaissance. Fellow resident Ernest Kendrick challenged me. “Doctors don’t think fiction is science. To reach a medical audience, you need to connect this literature to medicine. Why not use Engel’s biopsychosocial model?”

How Mr. Glover Was Saved by His Boss and Then Almost Killed by His Doctors

George Engel, a psychiatrist who helped surgeons and internists understand their patients’ needs, had just published a paper demonstrating how his “biopsychosocial model” worked in the clinical setting. In contrast to the “biomedical model,” which focused on what was going on inside the human body in a circumscribed biomedical sphere, the biopsychosocial model encompassed the sociology of illness.1

Engel told the story of Mr. Glover, a man who had had a heart attack. The biomedical way of telling the story would be something like this: This fifty-five-year-old well-nourished, well-developed white man with a previous history of myocardial infarction began experiencing chest pain at 10:00 a.m. and was brought to the emergency room by ambulance at 11:00 a.m. He was hospitalized in the intensive care unit, where he experienced cardiac arrest due to ventricular fibrillation. His heart was successfully restored to its normal rhythm. The rest of his hospital stay was uneventful, and he was discharged to follow up with his internist.

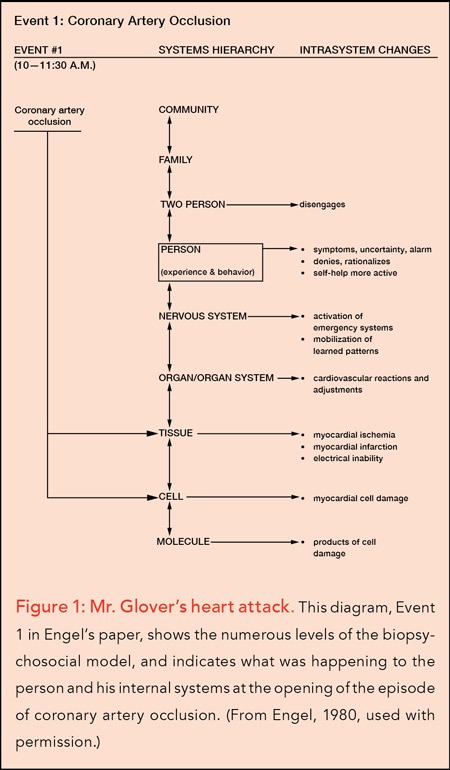

Engel’s approach to the story started at the same place, acknowledging that Mr. Glover had had a heart attack, a coronary artery occlusion, which affected the cell and tissue levels of the systems hierarchy, producing the symptom of pain that Mr. Glover experienced. (See Figure 1.)

But then Engel turned his attention to the hour between the onset of the heart attack and Mr. Glover’s arrival at the hospital. At first, Mr. Glover hoped that the feelings of unease and pressure inside his chest were signs of indigestion. He avoided talking to anyone in his office. As the pain increased, he realized that, if he were having a heart attack, he should get his affairs in order. Mr. Glover went off on that track, instead of going to the hospital.

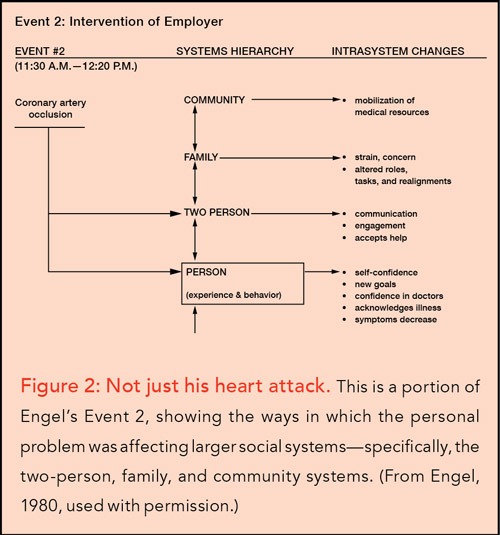

What was it that got him on the right course? Mr. Glover’s employer noticed his distress. She complimented him on his sense of responsibility, assured him that she and his coworkers would be able to manage because he’d done such a great job, and emphasized that his most urgent responsibility was to get well so that he could continue to be the fine family man and coworker she knew him to be. In the diagram for this event, Engel showed that while the processes inside Mr. Glover’s body were continuing, important systems outside of his body were being mobilized. (See Figure 2.)

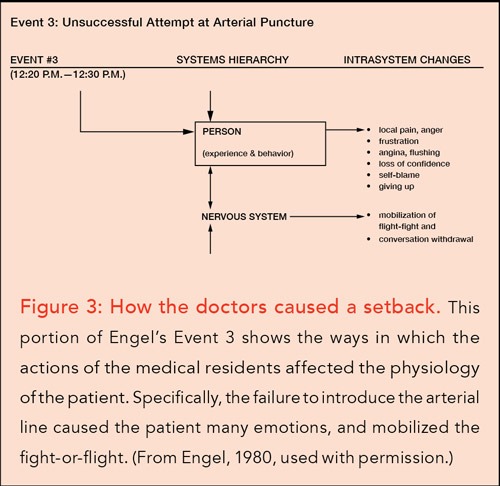

Once he arrived at the hospital, Mr. Glover was admitted to the intensive care unit on a protocol for those with heart conditions. He relaxed and accepted that he had had a second heart attack. The cardiac team wanted to put a catheter in Mr. Glover’s artery. The residents in charge of this task were not able to perform it. After several tries, they left to get help.

It was at that point that Mr. Glover had a near-fatal arrhythmia. Dr. Engel, in the diagram for this event, noted that at the person level, Mr. Glover experienced a wide range of emotions, including frustration, pain, anger, self- blame, and giving up, which mobilized responses of the nervous system, including the fight-or-flight reaction. The activated nervous system released a massive load of chemicals into the blood, which, Engel postulated, triggered the arrhythmia and cardiac arrest. Had the doctors taken the time to talk to Mr. Glover and learn the story of his dependence on authority, they wouldn’t have left him alone after a failed arterial puncture. (See Figure 3.)

Happily, Mr. Glover was successfully resuscitated. The rest of his recovery was “uneventful,” and he was discharged home. In taking us carefully through this assessment of Mr. Glover’s experience, Engel made the point that the biomedical model, which considered only the factors that were interior to the person, missed crucial events at higher levels of scale, including the patient’s experience of the event and the influence of other actors on the unfolding drama. When we have the full hierarchy of systems in front of us, we have a more accurate view of what is happening and better odds for saving the patient.

The Psychology of Place

It is this model that helped me link Fauset’s fictional coming-of-age stories to the real-world problem of skin color.2 I applied the model by systematically investigating each of its levels—person, family, community, and world— within the context of a past that was ultimately unknowable due to kidnapping and enslavement. I concluded, “The final integration of color in identity includes the known/unknown, chosen/rejected parts of self and society. In the consolidation of that identification it is the person who must grapple with truth, justice, honesty, and feelings for others. It is the person who at that moment becomes an adult.”3

Engel’s model proved to be a reliable companion as I plunged into the study of epidemics of AIDS, violence, and addiction that were sundering communities before my eyes. To get a handle on what was happening necessitated thinking constantly at many levels of scale.

This required a team of people and a window into the crises. I am reminded of the remarkable story of the documentation of digestion because a trapper named Alexis St. Martin had a gunshot wound that healed improperly, creating an opening to the stomach. Dr. William Beaumont recognized that this created an opportunity to peer into the workings of the stomach. This led to important discoveries about digestion and revolutionized the study of the human body.4

For me, the team and the window came together in 1990, when I was recruited to work at the HIV Center of Columbia University, located at the Columbia-Presbyterian Medical Center in New York City. While the Medical Center is a fortresslike building that dominates Washington Heights, the HIV Center arranged for my then husband, Bob Fullilove, and me to have offices at 513 West 166th Street, a large semi-abandoned building in the middle of a neighborhood that was traumatized by crack cocaine and all its related ills. To get to work, we walked down a sidewalk littered with crack vials, so prevalent there because one of the most important dealers in the area lived across the street. In that setting, walking to work was a constant source of inspiration.

We had other assets: We had a suite of offices that included a lounging area, and we had access to two conference rooms and a kitchen. We soon assembled the kind of multidisciplinary team that we needed to tackle the rapid- fire series of epidemics that were swirling around us. Calling ourselves the Community Research Group (CRG), we carried out studies of AIDS, crack addiction, violence, mental illness related to violence, and multidrug-resistant tuberculosis.

All of this was taking place in a context of social disintegration. Rodrick Wallace’s 1988 paper, “A Synergism of Plagues,” had been crucial to directing our work from the minute we received it.5 We were even more fortunate that Rod worked at the New York State Psychiatric Institute, part of the Medical Center, and was a willing collaborator and mentor. He taught us how a 1970s New York City policy called “planned shrinkage” had destroyed inner-city neighborhoods, dispersing the residents and creating the conditions for the rapid dissemination of the AIDS virus.

One of the first projects we undertook was to ask our intern, David Swerdlick, to take photographs of Harlem and to search in the archive of the Schomburg Center for images of what it used to be like. The contrast he documented was shocking: The structure of the neighborhood had been destroyed and its vitality vitiated. I could not explain in scientific terms how the built environment and social system were connected. Using the biopsychosocial model as my guide, I began to search in geography, environmental psychology, anthropology, sociology, and history to find the answers.

The geographers taught me about “place,” bounded areas that have social and psychological meaning, such as one’s home. The environmental psychologists explained that there are essential connections between individuals and place, as well as among residents of a given place, and between and among residents of different places. These are connections of attachment, such as those described by John Bowlby and others, the strong and weak social bonds that Mark Granovetter has described, and the powerful influence of behavior settings, established through the work of Roger Barker and his colleagues. Anthropologists and sociologists parsed crucial incidents, looking for clues. Anthony F. C. Wallace examined mazeway disintegration by looking at an attack on an Iroquois village; Alexander Leighton documented community response to upheaval by following how the Japanese managed internment; and Kai Erikson documented the aftermath of the disastrous flood at Buffalo Creek, West Virginia.6

From these scholars, I was able to piece together a set of propositions about the psychology of place.7 I tested my hypotheses by looking at place in the stories of my family, which I shared in my book House of Joshua: Meditations on Family and Place.8 The CRG team—Lesley Green Rennis, Jennifer Stevens Dickson, Lourdes Hernandez-Cordero Rodriguez, Caroline Parsons Moore, Molly Rose Kaufman, Bob, and I—was able to use the psychology of place in tracking epidemics, walking the streets, inventing interventions, and naming the chaos around us so that others might understand. We published over one hundred papers, several dissertations, and my second book on place, Root Shock: How Tearing Up City Neighborhoods Hurts America, and What We Can Do About It.9

Reading history was a major part of that work. The United States, despite arguing that its revolutionary fight was for “freedom,” established itself as a slave nation, preserving and protecting the rights of slave owners, and counting enslaved people as only three-fifths of a person. African Americans and their white allies carried out a sustained struggle to abolish slavery and establish freedom and equality. However, gains in the Reconstruction era were largely lost as inclusive democratic institutions were replaced by the Jim Crow system, which was later copied by admirers in Nazi Germany to create fascism and in South Africa to create apartheid. The long civil rights struggle, which we can date from W. E. B. Du Bois and William Trotter’s founding of the Niagara Movement in 1905, culminated in marked victories in the mid-1960s, with the signing of the Civil Rights Act, the Voting Rights Act, and the establishment of Medicaid, which desegregated hospitals.

A paradox of the post–civil rights era has been that the problems supposedly “fixed” by the movement have endured and even worsened. What emerged instead of an integrated nirvana was the “urban crisis,” a polite way of saying “inner-city black poverty.” Conservative politicians promulgated the idea that this was a failure of “personal responsibility,” which took hold in the public’s imagination but was patently false.10

The perspective of the psychology of place helps us track a different story, that of a series of forced displacements that had devastating effects on inner-city communities. Through that lens, we can appreciate the strength of segregated communities that managed to temper the ravages of racism through the Jim Crow era and build political power and many kinds of wealth. It was the power of these communities that was expressed in the civil rights movement. The example of the Montgomery bus boycott can illuminate this point. Rosa Parks’s legendary act of civil disobedience took place on Thursday, December 1, 1955. By Monday morning, December 5, at 6:00 a.m., fifty thousand black people initiated a boycott of the buses. For more than a year, they walked, endured threats and attacks, faced layoffs, organized carpools, fed one another, conducted weekly rallies, and held firm until they won. Only a very well-integrated, powerful community—one with deep spiritual principles—could have accomplished such a feat.11

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Against the backdrop of those impressive achievements, however, federal, state, and local governments had launched an attack on the collective power and wealth of African-American communities, which started with urban renewal, as carried out under the Housing Act of 1949.12 Known among black people as “Negro removal,” the Housing Act authorized cities to clear “blighted land,” using the power of eminent domain, and sell the land at reduced cost to developers for “higher uses,” like cultural centers, universities, and public housing. During the fourteen years of the urban renewal program, 993 cities participated, carrying out more than 2,500 projects. Of the one million people displaced, 63 percent were African Americans; the areas destroyed included substantial portions of such important black cultural centers as the Hill District in Pittsburgh and the Fillmore in San Francisco.

The Kerner Commission’s study of civil disorder in 1967 included urban renewal in the list of factors that triggered the rebellions.13 The process of urban renewal tore communities apart, destroying their accumulated social, cultural, political, and economic capital, as well as undermining their competitive position vis-à-vis neighborhoods that were not disturbed.14 This profoundly weakened affected neighborhoods; those harms were repeated in subsequent displacements due to planned shrinkage, mass incarceration, HOPE VI (which was directed at federal housing projects), the foreclosure crisis, and gentrification.15

The series of displacements from neighborhoods occurred contemporaneously with deindustrialization, which undermined the economic foundations of older American cities, leaving unskilled workers at a severe disadvantage.16 This created the massive deindustrialization diaspora to the Sun Belt, destabilizing both sending and receiving cities. In the upheaval caused by serial displacement and deindustrialization, the epidemics of heroin and crack cocaine took off, violence soared, and AIDS became a serious threat to health. Asthma and obesity flourished. Trauma, as a result of these accumulating disasters, became a major source of psychiatric illness and contributor to ill health.

The economic and social dismemberment of African-American communities stole their wealth, their power, and their capacity to engage in problem solving. Returning to the biopsychosocial model, we can begin to name the processes that are happening at each level of scale. The vulnerability of the individual stripped of the protection of a known and loved place is greatly increased. The experiences of trauma, grief, and anger, as well as the stress of losing one’s embedding community, have effects on the individual. These can lead to psychiatric illness, the use of drugs and other addictions, eating and autoimmune disorders, and infectious diseases.

At the level of the neighborhood, the processes of urban renewal, deindustrialization, and planned shrinkage are centrifugal: They are pulling us apart from one another. In my book Root Shock, I described the ways in which the centrifugal processes tear at people’s places and their lives. I asked the question, “When the center fails, what will hold?”

The answer in the short term is that people take on the work of place in order to keep their lives together. They band together in groups defined by “strong ties,” the ties of family, religion, and tribe.17 Yet these ties partition society. In the aftermath of urban renewal and planned shrinkage, the reformation of society around strong ties fed antagonism and intergroup hostilities: The solution became part of the problem, triggering a reinforcing, exhausting, and dangerous downward spiral.

At the next level of scale, the effects of neighborhood destruction on the larger embedding society are very serious. This point is often overlooked, because, as I’ve described here, the neighborhoods that are destroyed are those of poor and minority people. The larger society is thought of as “white” and “middle-class,” and therefore comprising people whose lives and fates are quite different and even insulated from the problems of the disadvantaged. The ecologists who mentored me, Ernest Thompson, Michel Cantal-Dupart, and Rodrick Wallace, taught me about the fallacy in this assumption of separation.

Rodrick Wallace, with his colleague and partner, Deborah Wallace, documented the ways in which the systematic destruction of minority inner-city communities had direct connections to the health of the larger society. They emphasized that concentration of people in ghettos did not mean that the harms inflicted on those communities would be contained within those spaces. Concentration is not containment, they emphasized. In fact, they identified what they called the “paradox of Apartheid,” the finding that segregation actually tightened connections between communities thought to be divided by race and class.18

In light of this serious history, which poses a substantial threat to the whole country, Rod made one of the most important advances in our field of social psychiatry: He described the workings of collective consciousness in our segregated society. Drawing on a large body of literature in many fields of study, Rod articulated the workings of “distributed cognition,” the ways in which people think together, across time and space. He built on this work by examining the threats to collective consciousness posed by rigid, Manichean systems of racial segregation. I collaborated with him on a book entitled Collective Consciousness and Its Discontents. In that book, we pulled together the fields of distributed cognition and social history. We wrote:

[A] neighborhood [has the ability] to perceive patterns of threat or opportunity, to compare those perceived patterns with an internal, shared, picture of the world, and to choose one or a few collective actions from a much larger repertory of those possible and to carry them out . . . This phenomenon is, however, constrained, not just by shared culture, but by the path-dependent historic development of the community itself. Recent work demonstrates that “planned shrinkage,” “urban renewal,” or other disruptions of weak ties akin to ethnic cleansing, can place neighborhoods onto decades-long irreversible developmental, perhaps evolutionary, trajectories of social disintegration, which short-circuit effective community cognition. This is, indeed, a fundamental political purpose of such programs.19

Not Spared History

While CRG was learning history, we were not immune to the processes we were describing. CRG was not a group that got major grant funds for big, long-term studies. Instead, we survived on small grants and contracts that allowed us to track processes unfolding all around us. The recession dried up our usual sources, and the team had to disperse. Gentrification hit Washington Heights, and we were evicted from our home at 513 in 2008.

This turned our attention to problems of rebuilding: Where were we to go? Like others displaced by gentrification, we had to go somewhere. At first, this seemed like a catastrophe, but we realized it was an opportunity to follow the path other displaced people were taking. Visits to Orange, New Jersey, my hometown, soon led to our joining local leaders to found the “free people’s university” of Orange. Eventually, we reestablished our research group under the name Cities Research Group of the University of Orange. Our experience rebuilding taught us a lot and helped me integrate the many lessons I’d learned through the careful tutelage of the renowned French urbanist Michel Cantal-Dupart, known universally as Cantal. I became deeply aware that rebuilding was about fixing the injuries to place as well as mending the social fractures.

In Urban Alchemy: Restoring Joy in America’s Sorted-Out Cities, I presented nine elements of urban restoration I’d seen Cantal and others use in the rebuilding process: Keep the whole city in mind, Find what you’re FOR, Make a mark, Unpuzzle the fractured space, Unslum the neighborhoods, Create meaningful places, Strengthen the region, Show solidarity with all life, and Celebrate your accomplishments. These elements guide us toward the work that needs to be done, slowly and carefully, building on the existing assets of our cities.20

Main Street in the Mix

While working on that book, I went to downtown Englewood, New Jersey, to get some coffee at Starbucks. I was sitting by the picture window, looking at the crowds passing by, and was struck by the liveliness of the scene. I, like most people, thought of Main Street as dead; but that day, I realized our Main Street was not dead at all. I started to think of all the functional Main Streets I knew and loved, civic, commercial and social centers that had been part of my life since childhood. Then I thought, if Main Streets are alive, what role are they playing in making our common life?

I started with the plan that over the coming year I would visit Main Streets in one hundred cities. It took longer and was harder than I thought it would be to discern the contribution of Main Streets to our collective mental health. From visits to Main Streets in 178 cities in fourteen countries, I have learned that these civic and commercial centers are designed and built to provide a centripetal—gathering— force for a community. Our survival is built on people’s coming together, and our social nature has evolved to reinforce gathering with pleasure. We have a built-in “Joy of Being In,” which explains the powerful “Fear of Missing Out.” When we go to Main Street, we take in fashion, culture, and sociability. We shop, mail letters, get library books, and have coffee. Or we loiter, whether on a bench or in a Starbucks window. Sometimes we take our laptops to be in the flow and in the know while ostensibly working. This makes us happy. It is a Machine for Living.

I also learned that this Machine for Living can be adapted to help us solve the horrific problems we face now: climate change, racism, militarism, and concentration of wealth, among them. One of my favorite Main Street spots is the Thomas Edison National Historical Site in West Orange, New Jersey—Edison’s “Factory of Invention.” It turns out that Edison needed a lot of people to get from idea to patented product. And he needed materials, spaces to experiment, ways to document the process, a library, and a couch for naps. The Factory of Invention is the remarkable space in which these things were meticulously organized as a place of distributed cognition.

Because of his recognition that this was the way people can innovate, Edison received 2,332 patents. While respect for his fertile imagination is universal, few of us know of the system that supported it. At the heart of that system was not a single great man, but, rather, a very large team that could think together, a working group with a massive collective consciousness, informed by science, mechanics, art, and imagination. It should not be a surprise that Edison’s Factory of Invention had a movie studio and a chemistry lab. This ability for humans to think in a collective manner is an extraordinary evolutionary advantage. Emphasis on collective: Had Edison not been hobbled by such antisocial character defects as anti-Semitism and belligerence with competitors, he might have died with four thousand patents.

When I first visited the Factory of Invention, I understood immediately that we at CRG had had such a factory at 513, where we could track epidemics and explain their social roots. Our factory, I would say, encompassed the whole neighborhood, which we scoured in our search for comprehension. We also had the luxury of a suite of offices that included places to share, to chat, to do the collective work of comprehension, what Rod would come to call “collective consciousness.” We could sit in the lounge or a conference room and pool our knowledge, tossing ideas around until we came to an understanding that fit all the facts.

One of my tasks in the wake of our displacement has been to rebuild CRG’s factory of invention. But I’ve also realized that the challenges and resources of Main Street offer groups large and small their own “factories of invention.” In the course of my study of Main Streets I’ve encountered many of these organizations. I am deeply impressed by what they have accomplished and what they might do next. Main Streets offer a unique combination of assets that can help us name and solve our problems.

But this potential tool is not in good shape. While Main Streets are not dead everywhere, many are. It took me a while to see this. Perceiving what is not there is tricky: It is the task of seeing the black hole. When Main Streets disappear, the center is gone; people are thrown into a centrifugal crisis. When enough of the disparate centers are gone, whole regions are impaired. When enough regions are reeling, the nation becomes paralyzed. When enough nations are paralyzed, the world falls into profound crisis.

And this is the situation in which we find ourselves currently: a dark situation with too little connection to make problem solving possible. Mounting crisis may force us to work together, but increasing anxiety may feed anger and hatred faster than solidarity. In our terrified apartness, we could fall into the worst possible outcomes of the current crises of climate change, species extinction, and international warfare.

Greta Thunberg, a teenage leader in the fight to face climate change, called on us all to shift to “cathedral thinking.” As she said to the European Parliament:

It is still not too late to act. It will take a far-reaching vision, it will take courage, it will take fierce, fierce determination to act now, to lay the foundations where we may not know all the details about how to shape the ceiling. In other words it will take cathedral thinking. I ask you to please wake up and make changes required possible. To do your best is no longer good enough. We must all do the seemingly impossible.21

I contend that cathedral thinking is another term for Factory of Invention. We can create on Main Street the spaces and sentiments for collective problem solving, so that we might transform these magnificent Machines for Living into the Factories of Invention that can see us through.

Notes

- George Engel, “The clinical application of the biopsychosocial model,” American Journal of Psychiatry 137, no. 5 (1980): 535–44.

- See Mindy Thompson Fullilove and Tyrone Reynolds, “Skin Color in the Development of Identity: A Biopsychosocial Model, Journal of the National Medical Association 76, 6 (June 1984): 587–91.

- Ibid., 590.

- Tia Ghose, “Man With Hole in Stomach Revolutionized Medicine,” Live Science, April 24, 2013, www.livescience.com/28996-hole-in-stomach-revealed-digestion.html.

- Rodrick Wallace, “A Synergism of Plagues: ‘Planned Shrinkage,’ Contagious Housing Destruction, and AIDS in the Bronx,” Environmental Research 47, 1 (October 1988): 1–33.

- See John Bowlby, Attachment and Loss: Volume I: Attachment (London: The Hogarth Press and the Institute of Psycho-Analysis, 1969); Mark Granovetter, “The Strength of Weak Ties,” American Journal of Sociology 78, no. 6 (May 1973), 1360–80; Roger Garlock Barker, Ecological Psychology: Concepts and Methods for Studying the Environment of Human Behavior (Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press, 1968); Anthony F. C. Wallace, “Mazeway Disintegration: The Individual’s Perception of Socio-Cultural Disorganization,” Human Organization 16, no. 2 (1957): 23–27; Alexander Hamilton Leighton, The Governing of Men (1945; repr., Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2016); and Kai T. Erikson, Everything in Its Path (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1976).

- See Mindy Thompson Fullilove, “Psychiatric implications of displacement: contributions from the psychology of place,” American Journal of Psychiatry 153, 12 (December 1996): 1516–23.

- Mindy Thompson Fullilove, The House of Joshua: Meditations on Family and Place (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 1999).

- Mindy Thompson Fullilove, Root Shock: How Tearing Up City Neighborhoods Hurts America, and What We Can Do About It (New York: One World/Ballantine Books, 2004).

- David Harvey, A Brief History of Neoliberalism (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005).

- Martin Luther King , Stride Toward Freedom: The Montgomery Story (New York: Harper & Row, 1958; repr., London: Souvenir Press, 2011).

- See Fullilove, Root Shock.

- Report of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders (Washington, DC: S. Government Printing Office, 1968).

- Fullilove, Root Shock.

- See Mindy Thompson Fullilove and Rodrick Wallace, “Serial Forced Displacement in American Cities, 1916–2010,” Journal of Urban Health 88, 3 (June 2011): 381–89.

- Barry Bluestone and Bennett Harrison, The Deindustrialization of America: Plant Closings, Community Abandonment, and the Dismantling of Basic Industry (New York: Basic Books, 1982).

- Granovetter, “The Strength of Weak ”

- Rodrick Wallace and Deborah Wallace, “Emerging Infections and Nested Martingales: The Entrainment of Affluent Populations into the Disease Ecology of Marginalization,” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 31, 10 (October 1999): 1787–1803.

- Rodrick Wallace and Mindy Thompson Fullilove, Collective Consciousness and Its Discontents: Institutional Distributed Cognition, Racial Policy, and Public Health in the United States (New York: Springer Science+Business Media, 2008).

- Mindy Thompson Fullilove, Urban Alchemy: Restoring Joy in America’s Sorted-Out Cities (New York: New Village Press, 2013).

- “‘It Will Take Cathedral Thinking’—Greta Thunberg’s Climate Change Speech to European Parliament 16 April 2019,” New Story Hub, April 17, 2019, com/2019/04/it-will-take-cathedral-thinking-greta-thunbergs-climate-change-speech-to-european-parliament -16-april-2019/.