May 18, 2017; New York Daily News, “Opinion”

Universal Pre-K is widely viewed as an important part of the nation’s efforts to give all children, particularly those raised in poverty, a quality education that will allow them to flourish in their adult years. But is it so important that early childhood educators should be subsidizing the cost of its expansion?

Preschool programs can be expensive to operate, and funding remains an obstacle. Often missed in the discussions of whether taxes should be increased or funds diverted from other programs in order to create new Pre-K classes is the question of whether early childhood teachers should subsidize the cost of their own programs.

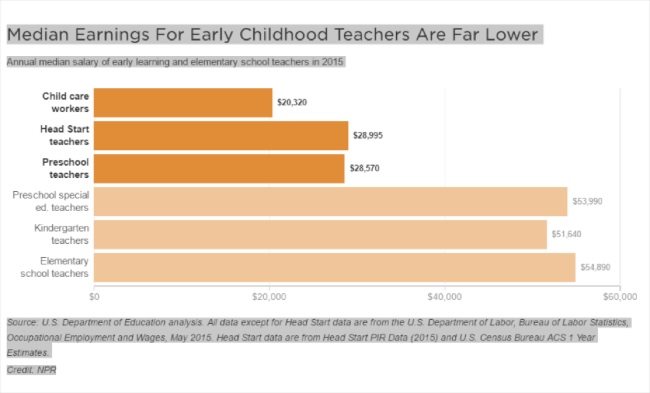

Low salaries have been a hallmark of early childhood education. Ruth McCambridge, in a previous NPQ story, referenced a study by UC-Berkeley’s Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, which found,

Early educators are among the lowest-paid workers in the country. The median hourly wages for child care workers range from $8.72 in Mississippi to $12.24 in New York. Nationwide, the median wage is $9.77. Preschool teachers fare somewhat better: wages range from $10.54 in Idaho to $19.21 in Louisiana. In contrast, the median national wage for kindergarten teachers is $24.83. Nearly one-half of childcare workers (46 percent), compared to 26 percent of the U.S. workforce, are part of families that participate in at least one public assistance program, such as Medicaid or food stamps.

Earlier this year, New York City began expanding preschool opportunities, with the goal of enrolling every three-year-old child. The city estimated it would need an additional $700 million to serve the estimated 5,700 children ($123,000/child) for this expansion. Even in a city as rich and liberal as New York, this is difficult to fund and those costs depend on keeping salaries down.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

According to Dave Nocenti, writing in the N.Y. Daily News, the disparities between similarly trained teachers in public kindergartens and in publicly funded preschools operated for the city by nonprofit organizations range from 32 percent to 113 percent, depending on their years of teaching.

In the public schools, lead classroom teachers with master’s degrees and state certifications earn a starting salary of $60,704. Those with 10 years of experience earn $82,995, and those with 20 years of experience earn $101,550…[Universal PreK] teachers with identical credentials—a master’s degree and state certification—get paid a starting salary of $50,000, with minimal longevity increases. Teachers with 10 or 20 years’ experience earn only $51,000 and $51,700, respectively. Even worse, the certified master’s-level teachers of two-year-olds and three-year-olds…make even less. Their salaries start at $46,000, and those with 20 years’ experience earn just $47,700.

Early Childhood Teachers work a 12-month school year for these salaries, as compared to the 10-month school year for their elementary school–based colleagues.

New York’s approach mirrors the national situation: Keeping early childhood educators’ salaries low does make funding easier. It leaves teachers, policymakers, and the public with an ethical dilemma that pits the welfare of teachers against the needs of the children they are trained to teach—one noted in earlier NPQ coverage: “A major goal of early childhood services has been to relieve poverty among children, yet many of these same efforts continue to generate poverty in the predominantly female, ethnically and racially diverse ECE work force.”

Too many teachers are leaving the field in order to support their own households, resulting in a shortage of qualified, experienced early childhood personnel. “The result,” Nocenti writes, “has been a severe shortage of certified teachers…and the teachers who remain—who are mostly women of color—are left wondering why the city is treating them like second-class citizens by refusing to approve salaries on par with those of their public school counterparts.” Turnover rates are also high. creating an unstable educational environment in classrooms where educational quality requires stability.

Can we find a way to meet the needs of both children and their teachers? If we think quality matters when it comes to our children’s education, we must.—Martin Levine