June 2, 2020; New York Times

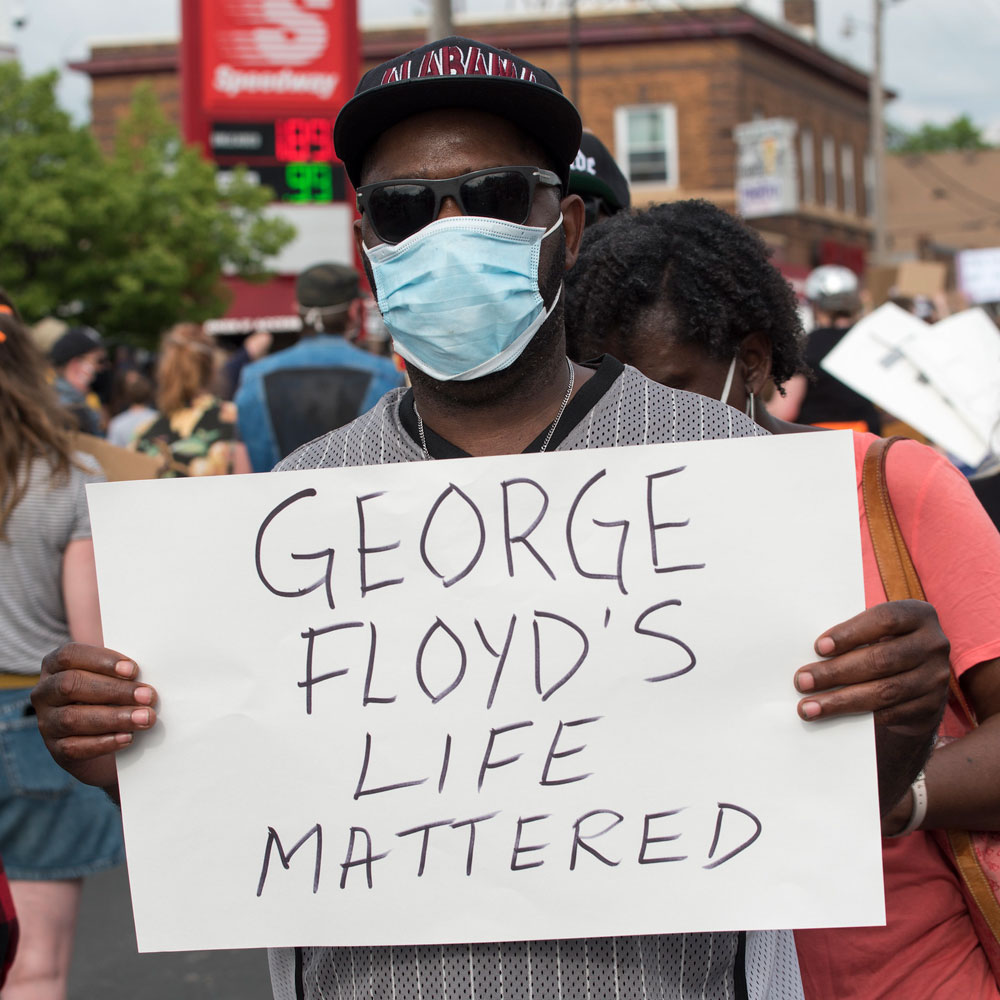

In response to multiple incidents of anti-Black violence, both by police and vigilantes—including the extrajudicial execution of George Floyd in Minneapolis—public demonstrations have now taken place in well over 100 cities nationwide. But as Emily Badger writes in the New York Times, this time the urban geography of protest is different.

In Los Angeles, both in the 1965 Watts Rebellion and the 1992 uprising after the Rodney King beating trial verdict, urban unrest focused on low-income neighborhoods south of downtown. This time, protests are centered in places like Hollywood, Santa Monica, and Beverly Hills, including famed Rodeo Drive. The same pattern, Badger observes, pervades the US urban landscape. In Chicago, protests have centered along Michigan Avenue, including its well-known Magnificent Mile section. In Atlanta, protestors converged in the upscale neighborhood of Buckhead. In Philadelphia, instead of North Broad Street, the focus of protests this time has been in ritzy Rittenhouse Square.

As Badger points out, a vastly changed urban landscape has developed over the past two decades. “Decent manufacturing and clerical jobs,” she notes, have “all but disappeared, replaced by a vast low-wage service sector. And the gaps between the most prosperous neighborhoods and those still trapped in poverty grew wider and more visible.”

While once cities might have been sites of disinvestment, today they are often sites of a high level of investment, but with a type of investment that largely excludes residents of color, even in cities where people of color are the majority of city residents.

Badger points out that in the nation’s capital, alongside “Black Lives Matter,” scrawled on several buildings was another slogan: “Eat the Rich.”

“The anger being felt is not just the deep injustice of police brutality,” notes Saru Jayaraman, president of One Fair Wage, a nonprofit advocacy group that advocates for fair wages for fixed workers.

The importance of this matter, Jayaraman notes, has been underscored, as many tipped workers, who had depressed wages because federal law allows them to receive a very minimal “tipped minimum wage” of $2.13 an hour, found out they did not have a sufficient wage base to qualify for state unemployment insurance—even as large corporations get millions in aid.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

In this light, it is worth noting that Floyd himself was a restaurant worker—a security guard at a Minneapolis restaurant and nightclub. And he had lost his job in the pandemic.

The dynamic that now dominates so many US cities is one where a service class works but does not live in the upper-income neighborhoods that have proliferated in many US urban centers. For instance, in the Buckhead neighborhood of Atlanta, Badger writes, “Black workers before the pandemic staffed stores where they couldn’t afford to shop and served meals in restaurants where their wages wouldn’t cover dinner. Now, protest is happening there, too.”

George Chidi is a longtime writer in Atlanta, as well as a homelessness advocate. Chidi notes that, “People are trying very hard to avoid the word ‘serf,’ but that’s kind of where we are right now. Honestly, we’ve created a class to exploit.”

Who belongs to this class? Badger explains that the pre-COVID Atlanta economy relied heavily “on hotel clerks, nannies, gardeners, house cleaners, car washers, Uber drivers, janitors who clean fancy gyms, and couriers who deliver from trendy restaurants. Jobs like these are what tend to be available now to workers without a college degree who 50 years ago could have found middle-class work in factories and offices.”

Massachusetts Institute of Technology economist David Autor has used the term “wealth work” to denote an emerging subset of service sector workers, such as baristas who make $7 lattes or personal trainers who work in gyms. Such jobs often offer limited pay, but what is important to recognize is that the jobs depend very deeply on the wealth of their consumer beneficiaries. “There are a lot of people who are there to serve the comfort and convenience and care of affluent individuals,” Autor tells Badger.

Such low-wage jobs in cities are disproportionately held by workers of color. And these workers have been hit extraordinarily hard by the pandemic. Not so long ago, Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell, observed that nearly 40 percent of Americans earning $40,000 or less lost their jobs this past March. By comparison, April unemployment for managerial and professional workers is a much lower 7.7 percent.

Meanwhile, as Jayaraman observes, anger continues to build about “the injustice of the corporate control of our democracy and the one percent really benefiting off the fruits of their labor.”—Steve Dubb

Correction: This article has been altered from its original form to update the current position of Saru Jayaraman.