November 1, 2017; CityLab

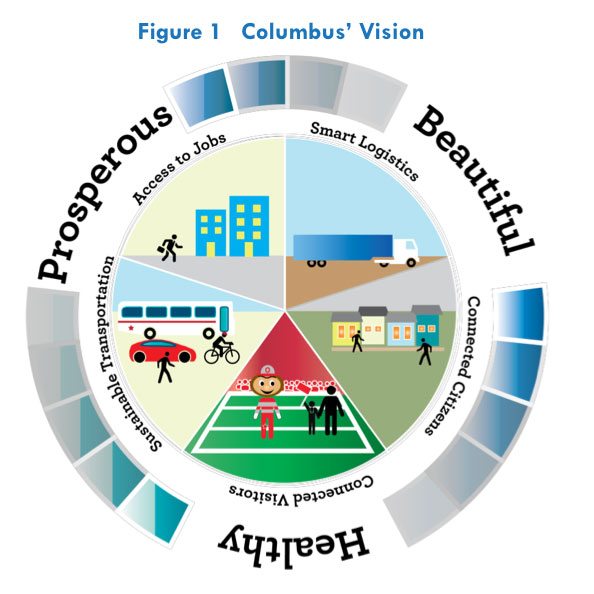

As Laura Bliss writes for CityLab, Columbus, Ohio “scored a $50 million jackpot” when it won a 78-city Smart City competition in June 2016. Columbus set high expectations in its proposal:

Part of the winning Columbus proposal was a vision of connecting low-income South Linden residents with better means of accessing medical care, jobs, and education. This was a novel model—a transit revamp aimed at saving lives, not just commute time. A central aim: reduce infant mortality by 40 percent by 2020, the city’s existing goal.

As Bliss writes, in the largely Black neighborhood of South Linden, “unemployment is triple the rest of Columbus, and incarceration rates are more than six times higher.” Bliss adds that the neighborhood is full of single mothers (it’s in the 99th percentile of all neighborhoods per capita), with median income of $21,000; few own cars. Bliss adds, “For every 1,000 babies that are born in Franklin County every year, nearly nine die before they turn one, compared to about six nationwide. Just eight neighborhoods, including South Linden, are responsible for nearly half of those deaths. The racial disparity is stark, with almost three times as many Black babies dying as white ones… Nearly 23 percent of women who make prenatal appointments at Columbus’ free clinics do not show up.”

In its grant application, Columbus wrote that it would change those numbers. After the award was given out, Adrian Marshall in Wired effused:

So what will life in Columbus look like? Let’s start in Linden, the heart of the city’s winning, 75-page proposal. The lower income northeastern neighborhood suffers from serious mobility issues: too few bus shelters, a lack of sidewalks and street lighting, and dangerous intersections, to name a few. Meanwhile, more than 20 of every 1,000 South Linden babies die before they turn one—almost four times the national rate—but there’s not a single obstetrics or gynecology office in the area.

Some day soon … a pregnant woman will walk up to an “ATM” near her house and add money to her city-issued all-access transit pass. She might … check transit schedules, see bike availability at new Linden CoGo bike share stations, or call a ride share service. The kiosks will have another, more Linden-oriented feature—our protagonist can use them to make pre-natal appointments…

When it’s time for her appointment, she can board the new Cleveland Avenue bus rapid transit line. Thanks to a network of sensors that detect and prioritize transit and emergency vehicles, she’ll see nothing but green lights.

Adam Stone of Digital Communities highlighted the mechanics in an article titled, “How Smart Transportation Projects Can Help Solve Social Issues.”

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

In many cases, local residents don’t have credit cards, which means they cannot use ride share services. That’s a problem when their homes and their physicians’ offices may be located some distance away from bus lines. The city wants to develop kiosks where locals can turn cash into electronic currency, making ride share accessible.

The plan also calls for streetlight-mounted free Wi-Fi, which could help residents connect with ride share or get information on public transportation routes and schedules.

Jeff Ortega, assistant city director of public services and part of the Smart City team, notes that the Columbus proposal wasn’t about “using technology to solve a commuting problem, getting from here to there. It was about using transportation to really solve community problems.”

Columbus has since parlayed the federal $50 million into a $500 million pool. But implementation of equity goals has been slow. The city did hire a firm that recommended a “cellphone-based platform that would allow moms to communicate via SMS with medical care providers and shuttle drivers when they needed rides to the doctor, and automatically arrange pick-ups through traditional van contractors or newer ride-hailing services like Uber or Lyft.” But there is no pilot. According to Brandi Braun, deputy innovation director, no implementation decisions have been made yet. Bliss adds:

But when I ask her if new and expectant moms in Linden were truly a target population of the grant…Braun hesitates. None of the Smart City projects were ever going to singlehandedly solve for infant mortality, she says. That health crisis and the families most affected by it “are one piece of the puzzle,” she says. Broader-based investments—such as the bus upgrade along Cleveland Avenue that’s set for 2018, and universal fare cards that Braun says will eventually move forward—are supposed to indirectly serve this population.

Bliss writes that some residents see signs of a “bait and switch” in progress. Jonathan Beard, a longtime community developer at the Columbus Compact Corporation, “points to a host of unkept promises in the historically black and now-gentrifying King-Lincoln district, and the recent demolition of a public housing project that had been a point of pride for Columbus’s black community and listed on the National Register of Historic Places.”

Bliss adds:

In Beard’s view, the Smart City proposal could be an urban renewal scheme in the worst sense of the term: South Linden’s position between booming downtown Columbus and wealthier suburbs to the north could make it a strategic target for investments destined more for gentrifiers. “Columbus is all about real estate,” he says. “They move black folk around this city like you move a pawn around the chess board.”

Jason Reece, an Ohio State urban planning professor whose research helped inform the city’s grant proposal notes that, “Technology doesn’t necessarily trickle down to serve those folks who are most in need. You have to put the people you’re going to focus on in the forefront.”

Reece adds: “We need to be hyper-focused on the needs [of this population] … This is the piece I’m going to be keeping my eye on: Are we really doing what we said we’d be doing? Are these efforts really serving people on the ground?”—Steve Dubb