October 10, 2018; Colorlines

When we think of discrimination in this country, many of us bring to mind images of the Civil Rights era and its marches and sit-ins to gain rights for African Americans. Some may remember the movement for rights for migrant, mostly Latinx workers. And because we are near the midterm elections, issues around voting discrimination bring the focus its impacts on the poor, the young, people of color, and the elderly. But if we look at the history of our country from the moment white people set foot on the North American continent, discrimination has had one longstanding target: the indigenous populations.

Native Americans, like slaves and other non-white peoples, were not granted citizenship at the founding of this country. They were not counted in the census (as were slaves and women, who also could not vote), as they were part of their own sovereign nations with their own lands and government. But that did not stop the new and growing United States from usurping Native lands and pushing the people onto designated reservations.

The history of the United States’ relations with Native Americans is one of conquest, dominance, and greed, full of bloody battles, court cases, and forced marches west into areas with limited resources and access to opportunities. Then, from around 1830, when the Indian Removal Act was passed, through the Civil War, a new tactic was initiated: assimilation. Using Christianity as a key, churches worked with Native American populations on the reservations to convert them and, in sending their children to boarding schools, strip them of their tribal customs. In 1887, the Dawes Severalty Act offered Native Americans citizenship if they would leave their tribes and take individual allotments of tribal land to live on. The final blow came in 1898 with the Curtis Act, which abolished all tribal governments and tribal courts and subjected Native populations on reservations to federal law.

But, if these American Indians were to reside on federal lands and be subject to federal law, then should they not be citizens of the United States, with all of those rights and privileges? The 14th Amendment granted citizenship to former slaves after the Civil War, but it did not encompass Native Americans. In the face of all this, as the 19th century slowly shifted into the 20th, Native Americans fought back, looking for options to establish their rights.

As Indians were removed from their tribal lands and increasingly saw their traditional cultures being destroyed over the course of the nineteenth century, a movement to protect their rights began to grow. Sarah Winnemucca, member of the Paiute tribe, lectured throughout the east in the 1880s in order to acquaint white audiences with the injustices suffered by the western tribes.

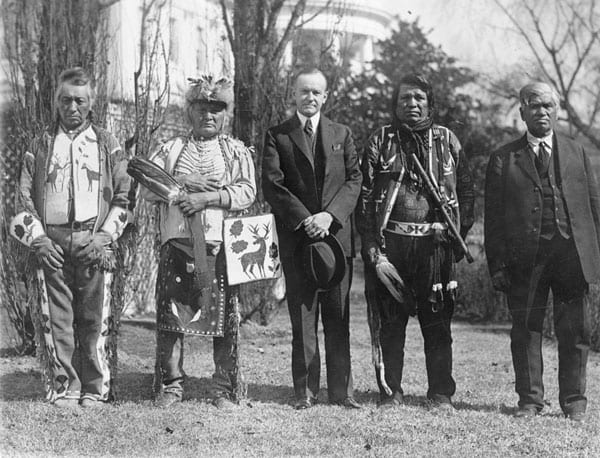

Lakota physician Charles Eastman also worked for Native American rights. In 1924, the Indian Citizenship Act granted citizenship to all Native Americans born after its passage. Native Americans born before the act took effect, who had not already become citizens as a result of the Dawes Severalty Act or service in the army in World War I, had to wait until the Nationality Act of 1940 to become citizens. In 1934, Congress passed the Indian Reorganization Act, which ended the division of reservation land into allotments. It returned to Native American tribes the right to institute self-government on their reservations, write constitutions, and manage their remaining lands and resources. It also provided funds for Native Americans to start their own businesses and attain a college education.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Discrimination against Native Americans runs deep and has continued into this century, with conflicts around tribal laws and local jurisdictions. Issues of poverty, unemployment, addiction, and educational inequality are common on most reservations. Becoming citizens has not catapulted Native Americans to comfortable, prosperous lives. And in states where their votes could make a difference in the outcome of an election, new forms of discrimination are surfacing. NPQ discussed this topic this week in North Dakota’s requirement for a “street address” in order to vote. This is a voter ID law that was specifically targeted to suppress the votes of North Dakota’s Native American population.

But this fight in North Dakota began years earlier against a different voter ID law. Just ask the Native American Rights Fund (NARF), which filed suit in 2013 against the ID law requirement, saying that it violated the US Constitution, the 1965 Voting Rights Act, and the North Dakota Constitution. All of the plaintiffs in this case could not vote in 2014 because of this law. In 2017, NARF won their case. North Dakota was charged with providing a new “fail-safe mechanism” that will help people who do not have the required ID in order to vote. And so, they came up with the ID including the voter’s current address. And, again, NARF called out the discrimination:

According to one study, more than 72,000 voting-eligible North Dakota citizens lack a qualifying ID. (That is in a total population around 750,000). Native Americans are more than twice as likely as non-Native Americans to lack a qualifying ID. Long distances, lack of transportation and limited operating hours at state driver licensing centers closest to Native American populations, make it more burdensome for Native Americans to obtain a state ID. Obtaining the needed documents also requires paying fees, which is more difficult for Native Americans because of economic disparities. On some reservations the unemployment rate tops 70 percent and incomes of Native Americans are, on average, half of what non-Natives earn in North Dakota.

Once again, NARF went to court, and again there was a stay issued. It came in time for the Native American population of North Dakota to vote in the primary election. But upon a request for an emergency appeal to the Supreme Court to reinstate the voter ID/street address plan before the midterm elections, the Court declined to prevent the state from enforcing the voter ID law. Only Justices Ginsberg and Kagan dissented. So, once again, a portion of the Native American population will be denied a right of citizenship due to circumstances that have been accumulating over years of suppression and oppression.

Is there a light at the end of this tunnel? Well, as NPQ reported, there is a group working on getting Native Americans in North Dakota legal street addresses as they enter the polls. This is all on the up and up, and breaks no laws. But the back-and-forth in the courts may have added to the confusion, and that alone can keep people away.

The goal of the white men who first set foot on this land was to push indigenous peoples into the background, seize their lands, and hope that they would fade away. They may not have envisioned a lack of a street address as a means of making Native populations disappear, but then, perhaps they were saving that option for a later date. That date may be now, as voter discrimination against Native Americans continues to rear its head.—Carole Levine