July 9, 2020; Thomson Reuters Foundation News

The past is the future in Tenino, Washington, a town of 2,000 about 60 miles southwest of Seattle. The town has revived its local currency that was first issued in 1931 to bolster the local economy during the Great Depression.

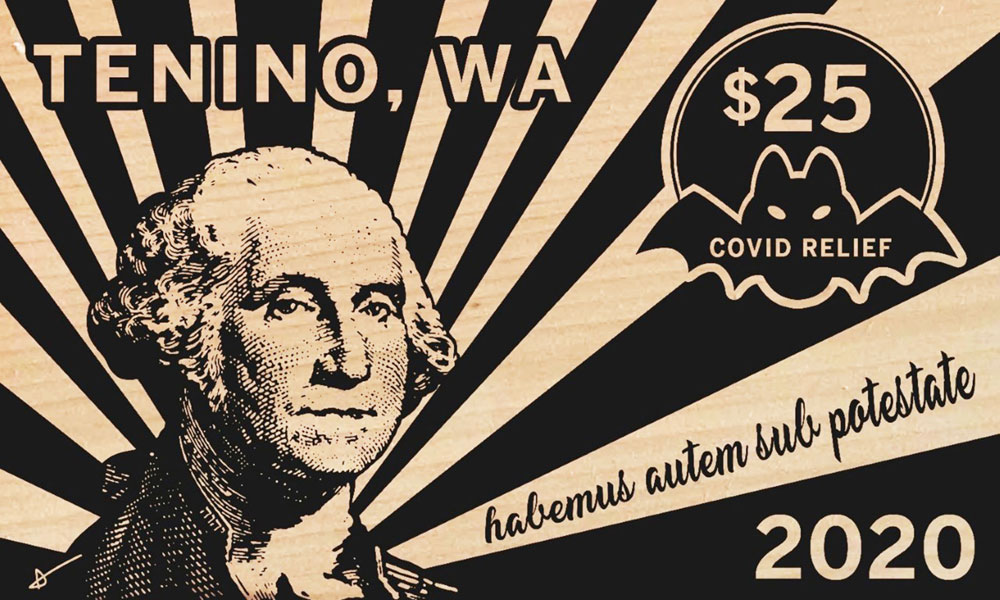

The original wooden printing press that minted the currency 90 years ago was tucked away in a former railway depot turned small-town museum. It’s now printing $25 wooden bills that are marked with the town’s name—Tenino—and the words “COVID Relief.” George Washington’s portrait, along with the Latin phrase “Habemus autem sub potestate” (“we have it under control”), harks back to our image of “real money.”

But this money is real. Tenino is offering $300 monthly in the local currency to any resident who can document loss of income due to COVID-19. The bills can be used to buy local goods (with the exception of booze, tobacco, cannabis, and lottery tickets), and merchants may exchange the bills at city hall for US dollars, $1 for $1.

Back in 1931, Tenino received some notoriety for its wooden currency, which was used to restore consumer confidence after the local bank failed.

“This is woven into the DNA of the community,” Mayor Wayne Fournier told Gregory Scruggs of Thomson Reuters Foundation. “My great aunt Erlene has the family collection all stashed away.”

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Fournier floated the idea of reviving the currency to the city council as a way to provide relief to local businesses and residents affected by the COVID-19 economic shutdown. In April, the Council approved a proposal to issue up to $10,000 in local scrip. With additional donations, the total funds have grown to $16,000.

According to the Schumacher Center for a New Economics, in 2019, there were at least 50 local alternative currencies worldwide. In 2014, NPQ covered a growing movement in the US to launch local currencies in response to the recession. Local currencies help boost local economies by encouraging consumers to buy local goods and services and keep cash circulating within the community.

Susan Witt, executive director of the Schumacher Center, explained to Scruggs that such alternative currencies “are better than direct cash payments at boosting local economies.” Witt points to Barcelona, where donations to sports teams and cultural groups in 2017 and 2018 were spent in big box stores, supporting multinational corporations rather than local businesses. Barcelona responded by creating a local currency “so that these ‘discretionary’ funds in its budget would circle back to support locally owned businesses.”

Mayor Fournier sees the Tenino wooden dollars as an alternative to the federal Paycheck Protection Program, which failed to reach the types of small businesses that populate Main Streets like his.

“A federal program dumps money from the top and these blue-chip companies steal it all,” Fournier told Scruggs. “If we do it from the ground up, there’s no stealing. It’s a direct ballast to Main Street.”

That may be so, but thus far, it seems that local residents haven’t taken advantage of the program. As of early July, only 13 residents had applied for $2,500 worth of local funds. At the local hardware and grocery store, manager Chris Hamilton told Scruggs that customers had spent only $150 of the local currency. He planned to take the dollars to City Hall to exchange them for US dollars, noting it hadn’t occurred to him to recirculate the currency with his own local purchases. But that’s the key to making the system work—keeping the currency circulating and growing the economy.

Despite the reluctance of local residents to embrace the Tenino wooden dollars, Mayor Fournier is getting plenty of calls from other local leaders interested in launching similar experiments in their own cities and towns. Perhaps removing the stigma of “COVID Relief” and making currencies broadly accessible from the start would increase the uptake and help to revive more communities across the US.—Karen Kahn