December 10, 2015; Center on Budget and Policy Priorities

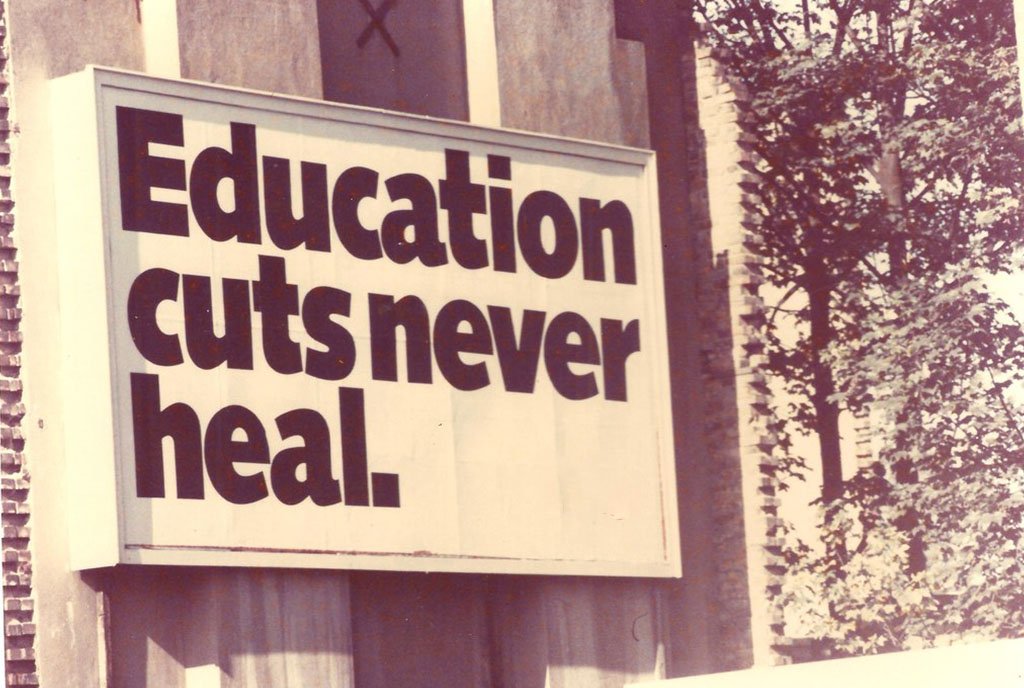

After reading the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities’ recent report, “Most States Have Cut School Funding, and Some Continue Cutting,” it seems that federal, state and local policymakers might want to remember this advice often attributed to Albert Einstein: “Everything should be made as simple as possible, but not simpler.”

Decades of effort and billions of dollars have been spent searching for ways to ensure that all children receive a quality education with little if anything to show for the investment. The CBPP report suggests that we may be missing a very simple fix: ensure that we adequately fund our schools.

Most states provide less support per student for elementary and secondary schools—in some cases, much less—than before the Great Recession, our survey of state budget documents over the last three months finds. Worse, some states are still cutting eight years after the recession took hold.

CBPP found that states made widespread and deep cuts to education formula funding when the recession hit, and at least half of the states still haven’t fully restored the cuts eight years later. After adjusting for inflation, twenty-five states are providing less general aid per student this year than in 2008. In seven of those 25 states, the cuts are 10 percent or more. In three states—Oklahoma, Alabama, and Arizona—the cuts are 15 percent or greater.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

The reasons that state and local funding for education has decreased are complex mix of economic and political factors. But the impact of lower funding on our schools is clear. At a very basic level, ensuring that there is a proper schoolroom for every child has become much more difficult in the face of sharp funding reductions:

Elementary and high schools nationally cut capital spending by $28 billion, or 37 percent between fiscal years 2008 and 2013 (the latest year available), after adjusting for inflation. Thirty-eight states cut capital spending over this period, in many cases drastically. Five states cut capital spending by more than half. Nevada, the state with the sharpest reductions, cut capital spending by 81 percent.

With more students to teach, funding reductions have resulted in a loss of almost 300,000 educators. CBPP also points out, “Many states have undertaken education reforms with federal encouragement, such as supporting professional development to improve teacher quality, improving interventions for young children to heighten school readiness, and turning around the lowest-achieving schools. Deep cuts in state K–12 spending can limit or stymie those reforms by limiting the funds generally available to improve schools and by terminating or undercutting specific reform initiatives.”

When viewed through a lens given to us by C. Kirabo Jackson, Rucker Johnson, and Claudia Persico in their recent paper, “The Effect of School Finance Reforms on the Distribution of Spending, Academic Achievement, and Adult Outcomes,” the CBPP findings take on greater meaning.

A 20 percent increase in per-pupil spending each year for all 12 years of public school for children from poor families leads to about 0.9 more completed years of education, 25 percent higher earnings, and a 20 percentage-point reduction in the annual incidence of adult poverty; we find no effects for children from non-poor families. The magnitudes of these effects are sufficiently large to eliminate between two-thirds and all of the gaps in these adult outcomes between those raised in poor families and those raised in non-poor families.

If we care about the education issues we seem to like arguing about, time to pay much more attention to Albert Einstein’s advice and worry about how we fund our schools properly and fairly.—Martin Levine