This is the first of a four-part series from the winter 2019 edition of the Nonprofit Quarterly, addressing the decline of small and medium-sized donor households. NPQ considers this issue an urgent matter for the entire sector.

The steady decline in the proportion of Americans who report making donations to charitable organizations is gaining more attention in the nonprofit sector, but it has yet to surface as a concern in private foundation spaces. The topic did not appear on any of the agendas of the major learning conferences for foundation staff this past year, hosted by groups like the Council on Foundations, Grantmakers for Effective Organizations, and Grantmakers in Health. With twenty million Americans having decided between 2000 and 2016 to stop contributing directly to charitable organizations,1 there should be concern not only for what this shift means for charitable organizations that depend on contributions from individuals to support their mission, but also concern among foundations. After all, foundations are themselves dependent on a healthy and thriving charitable sector to sustain the impact of their grantmaking and broad public confidence in charitable giving, as an underlying factor in their claims for legitimacy.

Although the apparent lack of awareness of or interest in this important trend is stunning, it is, to be fair, easy to miss the message of declining participation, when top-line messages in the media and in sector reports focus almost exclusively on the record high levels of charitable giving. According to the 2019 edition of Giving USA, giving by individuals totaled an estimated $292 billion, which represented a slight (and expected) decline from 2017 levels, but was still the second-highest amount in nominal dollars on record.2 Add to that the nearly $76 billion in foundation grants, the nearly $40 billion in bequests, and the $20 billion in giving by corporations, for a total of giving by individuals and organizations that reached over $427 billion in 2018.3 This paints a picture that is far from a crisis situation, even though the spread of this high level of giving is experienced unevenly across subsectors and organizations. However, these top-line figures that focus on the total levels of giving mask important and significant shifts in who is doing the giving.

The Disappearance of Low- and Middle-Income Donors

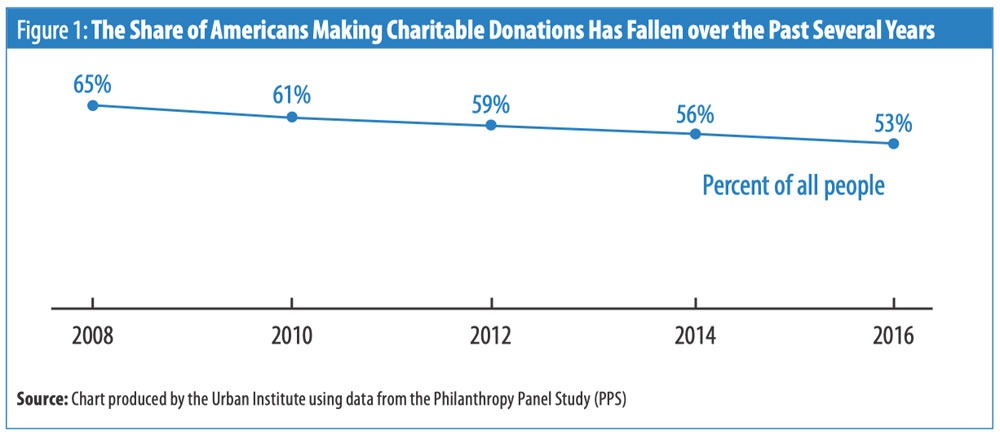

Figure 1 (below) shows the declining share of Americans who report that they have made contributions to a charitable organization. To be clear, this is not a measure of Americans’ overall generosity, since it does not capture giving outside the context of formal charitable organizations. It would be a mistake to conclude from this figure—as some do—that fewer Americans are participating in charitable giving, since it does not capture person-to-person giving, which is another way that individuals express their charitable impulses. Nor does it include political giving, which, like charitable giving, also serves as an expression of individuals’ values. What we can take away from this chart is that there is a declining preference for the kind of charitable giving that is directed to a charitable organization as the recipient. The record levels of giving reflect higher levels of giving by those who do give to charitable organizations.

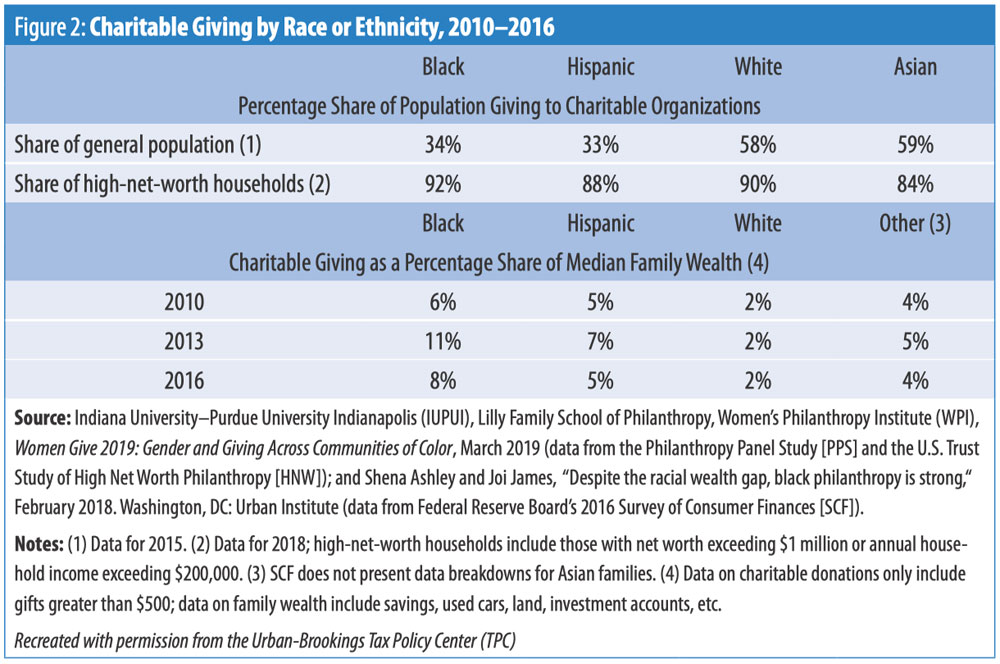

Figure 2 (following) provides a snapshot of this dynamic across race and ethnicity groups. Almost 60 percent of white and Asian households gave to charitable organizations in 2015. (Note that the data presented as share of general population are data for 2015.) Black and Latinx households were less likely to donate to charitable organizations. However, controlling for wealth, giving participation is higher in Black households than all other groups (i.e., percentage share of population giving to charitable organizations). For those who do give, the level of giving, measured as a share of median family wealth, is higher for Black and Latinx families than white or other families (i.e., charitable giving as a percentage share of median family wealth). Given the high level of participation in giving to nonprofit organizations among high-net-worth households across all race and ethnicity groups as shown in Figure 2, it is most likely that households choosing not to give to charitable organizations are in low- and middle-income households.

The Big Shift Away from Giving to Charitable Organizations

Evolving attitudes toward a focus on causes instead of organizations, and the growth in types of activities in which individuals can participate to feel connected to a cause, are part of the forces that are leading to decreased levels of participation in giving to charitable organizations. These organizations face greater competition for donors at a time when conscious consumption—or buying socially responsible goods—is increasingly being considered as a substitute for charitable giving, or when there is increased interest in receiving a monetary return through vehicles like impact investing or providing start-up capital to social enterprises.4

Additionally, the rise of social giving through the various crowdfunding platforms is reshaping the giving landscape by enabling the kind of person-to-person transactions that allow donors to directly help individuals in need of things like the means to cover medical expenses or memorial funds.

It is not clear whether these shifts are a result of donors’ increased interest in these new modes or if they are a reflection of dissatisfaction with nonprofit organizations among donors from low- and middle-income groups. What is made clear by these trends, however, is that donors are seeking impact through forms of giving that are not intermediated by charitable organizations in the traditional sense.

Unlike foundations, whose grantmaking is by and large restricted to charitable organizations, individual donors (especially those who are not seeking tax deductibility for their donations) have the flexibility to direct their donations to individuals or other types of nonprofit and social-welfare organizations.

Concerns for Foundations

What issues are raised for foundations when low- and middle-income donors are choosing to direct their donations to places other than charitable organizations? Two issues come to mind that reflect the complex interplay between individual and institutional philanthropy. The first relates to program sustainability, and the desire of foundations to see that the work they support through their grants continues beyond the grant cycle. The second relates to the legitimacy of foundations, and the reliance that foundations have on a general norm around charitable giving to underpin public support for the privileges they receive under the tax code.

Sustainability Implications

One measure of the impact of foundation grantmaking is whether the projects that foundations support or the capacities that they help to develop in nonprofit organizations sustain beyond the grant period. This metric is especially relevant to foundations that are working in support of community change in particular places, and among those who view their grants as investments in sustained community capacity for social change.

In this context, the availability of other sources of funding is an important environmental factor that will determine whether projects and capacities can continue beyond the grant cycle. For many organizations, government funding and fee-based revenue are viable options, but the playing field is not level when it comes to which nonprofits have access to these resources.5 For many community-based organizations, their path to sustaining projects and capacities relies on their ability to connect with and attract donations from individuals across their community.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

The loss of small and medium-sized donors who have stopped giving to nonprofit organizations—either because they are no longer able to make donations or have shifted their giving to alternative approaches—is of great concern for the small and medium-sized nonprofits that depend on individual donations for their programming and for the flexible capital needed to develop their capacities for greater innovation and impact. These, in many cases, are the same organizations that large, multipurpose foundations—which are trying to overcome historical legacies of distance and lack of transparency by connecting their work in closer proximity to the communities where they want to deliver impact—raise concerns about vis-à-vis the sustainability of the projects, and see this as a barrier to funding their work. This sustainability challenge is not tenable in the long term for community-based organizations and the important purposes they serve in maintaining a healthy and vibrant charitable sector.

Legitimacy Implications

With so much focus on the instrumental dimensions of charitable giving (who gives and how much), the underlying expressive values that are connected to charitable giving are often overlooked. In his 2006 book Strategic Giving: The Art and Science of Philanthropy, philanthropy, nonprofit management, and social entrepreneurship expert Peter Frumkin emphasizes the expressive quality of giving.6 He notes that giving is an expressive exercise through which donors project their commitments and beliefs onto the world. That donors may be choosing other forms of giving that help them make a connection to a cause rather than to an organization is, therefore, not itself a problematic situation. It is the act of giving—whether to an organization or to a person asking directly for help—that provides a valuable opportunity for all people to express interest in a cause that means something to them, or to have the opportunity to participate in the kind of social change they want to make possible.

However, the continued decline in the percentage of Americans choosing to give to charitable organizations presents something of a dismantling of the neat narrative (which, in part, was constructed, held together, and incentivized by tax policy) that giving to America’s charitable organizations is the preferred way to realize the expressive function of charitable giving. This narrative and the norms of giving that are connected to it are directly linked to the public’s understanding of and support for the role and functions of philanthropic foundations. In their introductory chapter to The Legitimacy of Philanthropic Foundations, Steven Heydemann and Stefan Toepler point out that the legitimacy of the foundation form benefits from deep public and official support for charitable giving, volunteering, and self-help.7 They note that foundations as institutions are the beneficiaries of deep normative commitments to charity that are so widespread as to be virtually universal.

The question, then, that the philanthropy field has to grapple with today, is: What happens when the normative commitment to charity through charitable organizations is no longer universally held—when tens of millions of Americans choose to stop giving to charitable organizations, or as new norms that bypass “the middleman” continue to take root? What does it mean, in other words, to be a formal, organized expression of a deeply held norm that is, undoubtedly, changing?

Institutional Philanthropy Needs to Wake Up to Its Interdependence with Individual Giving

Although there has been a concerted effort through the professionalization of grantmaking and through waves of operating frameworks (e.g., scientific, strategic, effective) to distinguish institutional philanthropy from individual giving, it would be a mistake to overlook the links between the two. They cannot be walled off from each other. They are both sources of revenue for many of the same organizations, and are parts of a broader conception of the field of American philanthropy. If foundation staff would zoom out to see themselves as part of a much broader philanthropic marketplace, they might be able to see opportunities to influence individual donations so that they, and their grantee partners, are less impacted by the changing dynamics in individual giving.

Three Ways Institutional Philanthropy Can Help Recapture Individual Giving

Foundations have always been active participants in addressing the environmental conditions that have the potential to limit their impact or undermine their legitimacy. Through public outreach, support for research or advocacy by infrastructure groups, or direct engagement, there are examples from the past where foundations have had to work to engage the public or build public support for their work. However, the challenge of shaping donor behavior and attracting donors back to charitable organizations will require more than public awareness—it will also require that foundations directly engage with individual donors and find ways to bring them along through their grantmaking.

Research suggests that individual donors already look to foundations for information on charities to make informed giving decisions. Although early economic studies hypothesized that foundation giving would crowd out private donations, more contemporary studies show that in many cases foundation grants attract private donors, because they provide a signal of charity quality. A recent study of Canadian social-welfare and community charities found that “an additional dollar of foundation grants to charities crowds in private giving by three dollars on average.”8

Building on this signaling effect, foundations can attract individual donors by designing campaigns for matching funds to their grantee partners. The results of an experiment by Dean Karlan and John List, published in 2012, show that lead donors can help charities attract other donors by announcing their gifts and by matching other people’s gifts with their own money.9 They found that announcing matching gifts from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation multiplied the number of donors who responded to a charity’s appeal. Their research provides further evidence that quality signaling through the foundation’s name can work to enhance both the size of gifts and the number of donors. (The Koch-affiliated Stand Together Foundation is one example of a foundation that took a deliberate step to build a network of everyday donors to support the grantee partners they had selected to participate in their antipoverty strategy, by launching a matching gifts program, the Giving Together Initiative, in which the foundation matches donations up to $1,000 each.)

A similar approach is to create opportunities for collaborative funding with individual donors. Co-Impact, an initiative housed at the Rockefeller Foundation, describes itself as a platform where donors can join in to support a portfolio of programs that the core partners have identified as strategies for systems change. This model was developed to provide individual donors with access to the kind of thinking and structures that are widely available in institutional philanthropy, to help them align their giving with opportunities of greatest impact. Models like this can be developed, where foundations can attract and educate donors by providing them with insight and expertise, including options like sharing program officers’ due diligence assessments, or giving donors summaries of the performance reports submitted to the foundation.

Another way foundations can assist their grantee partners is to help them adapt to the changing dynamics in charitable giving by funding donor-engagement programs. Many nonprofits simply lack the capacity and resources to respond nimbly to leverage some of the new technology and digital strategies available to engage donors effectively. The Evelyn and Walter Haas, Jr. Fund made significant investments in research and capacity-building support to help their grantee partners raise money from individuals, after hearing their grantees identify this as one of their major challenges. A related approach to building fundraising capacity is through planning grants and challenge grants, which provide organizations with the time and resources to design and test sustainability strategies for their programs. The Health Foundation of Greater Cincinnati (now Interact for Health), for example, developed a model for sustainable grantmaking to ensure that they were thinking with their grantee partners about ways to sustain programs funded by their grants.10

Finally, foundations can actively participate in shaping the culture of giving in the communities they serve.11 Community foundations have historically provided assistance and support to giving circles, which are helpful in connecting a community of donors and providing a social experience that donors want around their giving. Other examples include building awareness for individual donors around the issues the foundation supports. One example is provided by the Harman Family Foundation, in Washington, DC, which publishes a “Catalogue for Philanthropy: Greater Washington” to attract individual donors to small local nonprofits in the region. These are just a few examples of ways foundations can participate in supporting the philanthropic infrastructure beyond grantmaking by leveraging their communications, advocacy, convening, and research capacities.

…

The loss of millions of donors to charitable organizations presents an interesting juncture in the evolution of charitable giving, which could have effects that extend beyond nonprofits to institutional philanthropy. This calls for attention—if not action—on the part of foundations. As our understanding of the dynamics of donor giving unfolds through better data and research to help understand why and how donors are shifting their giving, the field will be able to develop targeted strategies for organizations to draw donors back to charitable organizations or adapt to the new reality of giving without the charitable organization as the intermediary. In the meantime, such silence as now exists within the philanthropic sector is not warranted. Foundations cannot remain comfortably unaware while everyday donors are walking away from charitable organizations.

Notes

- Chelsea Jacqueline Clark, Xiao Han, and Una O. Osili, Changes to the Giving Landscape (Indianapolis, IN: Indiana University Lilly Family School of Philanthropy at IUPUI, 2019).

- Giving USA, Giving USA 2019: The Annual Report on Philanthropy for the Year 2018 (Chicago: Giving USA, 2019), 19. (Note: Giving USA 2019 page numbers refer to a preprint PDF; page numbers may change when the report has been published in its final, bound form.)

- Ibid., 26.

- Urban Institute, “2018 Update: On Track to Greater Giving,” dashboard, Urban Institute, 2018.

- Shena R. Ashley and David M. Van Slyke, “The Influence of Administrative Cost Ratios on State Government Grant Allocations to Nonprofits,” Public Administration Review 72, no. s1 (November–December 2012): S47–S56.

- Peter Frumkin, Strategic Giving: The Art and Science of Philanthropy (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2006).

- Steven Heydemann and Stefan Toepler, “Foundations and the Challenge of Legitimacy in Comparative Perspective,” in The Legitimacy of Philanthropic Foundations: United States and European Perspectives, ed. Kenneth Prewitt et al. (New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 2006), 3–26.

- Iryna Khovrenkov, “Does Foundation Giving Stimulate or Suppress Private Giving? Evidence from a Panel of Canadian Charities,” Public Finance Review 47, no. 2 (March 2019): 382–408.

- Dean S. Karlan and John A. List, “How Can Bill and Melinda Gates Increase Other People’s Donations to Fund Public Goods?,” CGD Working Paper No. 292, Center for Global Development, July 9, 2012.

- Ann L. McCracken and Kelly Firesheets, “Sustainability Is Made, Not Born: Enhancing Program Sustainability Through Reflective Grantmaking,” The Foundation Review 2, no. 2 (2010).

- Benjamin Soskis, Analyzing a Localized Giving Culture: The Case of Washington, DC (Washington, DC: Urban Institute, December 21, 2018.)