You are likely to soon start hearing a lot more about the questionable value of Gifts In Kind (GIK). GIK are donations of materials or services to nonprofits, either for direct use or for resale. Several states’ attorneys general seem to be taking a strong interest in catching non-profits giving inflated value to these gifts.

The discussion is motivated by the variable value of a donated item. One person’s trash may be just that, trash, and not another person’s treasure. It doesn’t take an accountant to figure out how squishy the value of donated items could be; it just takes someone who has donated (aka dropped off) a couch that was too large for his or her apartment dumpster.

The government’s interest in this topic is pretty self-evident—and it’s about things far bigger than a discarded sectional recliner. In a nutshell, corporations can offset taxes on earnings with donations of excess production. This can result in unintended subsidies or support on the part of the government in the form of lost tax revenue.

One well-known scheme is the unloading of the runner-up’s Super Bowl champion shirt. For a comedic break and to see this in action, check out this SNL skit. Note the Super Bowl shirt that shows up; heartbreak for Bills fans again. No, they didn’t win in 1993.

When these shirts end up in a developing country, there is a cost to the donor country of origin in lost taxes—maybe as much as 10 or 20 times the resell value of the shirt in the recipient country. Lost tax dollars cost just like foreign aid—except without the vote by Congress and probably with even less positive impact.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

This issue takes on a whole new level (think millions) when it comes to donated pharmaceuticals. Check out this decision by the California Attorney General, who reduced the value of donated Simvastatin claimed by Food for the Poor from $924,671 to less than $5,000. Yes, that is a devaluation on the magnitude of nearly 200 times. (Not to spoil your read, but the California AG fined Food for the Poor over $1 million and issued a partial cease-and-desist order.)

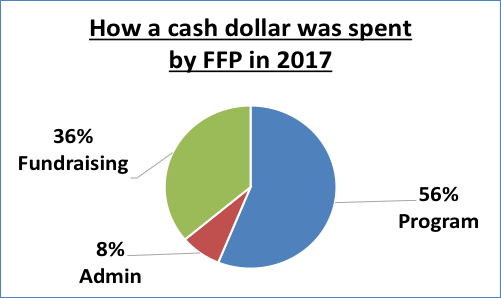

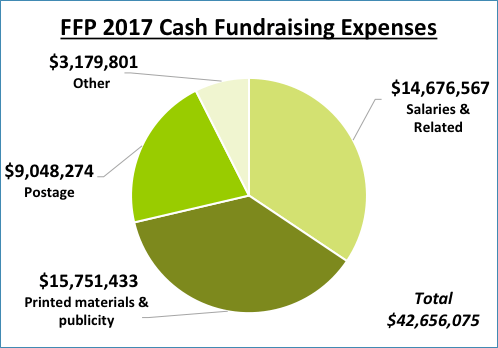

Savvy nonprofits brokering these donations can dilute their otherwise high costs of cash fundraising by mixing these high-dollar, overvalued in-kind gifts in with their cash revenue. A nonprofit may spend $20 million to raise $100 million in cash, but mix in $300 million of in-kind donations dropped at the door or, in some cases, directly to the end user at no cost—bingo, they’ve spent five percent on fundraising.

The mean side of this trick is that it covers up what happens to cash donations (see chart). Generally, nonprofits can’t use GIK to pay postage or for those obnoxious mailings. Cash donations, especially those small, hard-earned ones sent in by grocery clerks or by grandmothers on fixed income, get mugged!

If this topic interests you, you will likely enjoy these articles. It is a lot of reading (especially since you will need to read at least some of the 24-page finding by the California AG), but it is well worth it. I suggest reading them in the order presented.

- Slate: Is FFP achieving its mission?

- RRStar: Group not affected by scrutiny of builder

- RRStar Opinion: Article on FFP, HFH may mislead readers

As a bonus, I would suggest this article I wrote a number of years ago. It is an oldie but a goodie. It also lets me brag that I saw this coming.