August 8, 2018; Think Advisor

The latest IUPUI Women’s Philanthropy Institute report, “How Women and Men Give Around Retirement,” discusses four key findings about changes in giving and volunteering throughout retirement. Of the groups studied—single men, single women, and married couples—single women were the most consistent and stable in their giving, followed by married couples, and then single men. Following gender differences in volunteering for all life stages, single women and married couples were more likely to volunteer and are more stable in their volunteerism than single men.

The most volatile group across all factors studied was single men. We see a drop in their likelihood of giving right around the transition event of retirement, but this eventually bounces back up to pre-retirement giving levels shortly afterwards. The same seems to occur for giving amount. With volunteering, however, single men are less likely to volunteer after retirement. Single women, on the other hand, seem to increase their engagement in volunteerism after retirement, with married couples essentially remaining consistent before and after retirement.

When looking at this report in totality and stepping back to identify an overall theme, the biggest takeaway seems to be that post-retirement behavior reflects pre-retirement behavior. Those who give both time and money before retirement are going to continue giving into and during retirement. This is great news for nonprofit organizations for several reasons.

First, retirement is such a fluid concept these days. Some people choose never to retire, some take small retirements or take on a second career, others plan for it far in advance, and still others are forced to retire before they are ready to do so. But, findings in this report indicate that the event of retirement itself does not seem to have profound impacts on likelihood of giving or giving amount. Even while other discretionary spending and consumption decreases between the ages of 60–70 years, charitable giving remains consistent.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Secondly, we know it takes far more effort and money to acquire donors rather than to retain them. This report clarifies that retaining donors is not just good practice in the short term. With people living longer, nonprofits can expect to see larger lifetime values for donors they can retain.

Lastly, this report points to women as being important drivers of philanthropy both before and after retirement. We know that women are more likely to live longer than men and are set to inherit funds. The findings of this report indicate that women are also more likely to continue giving and give at higher levels than men. Taken together, this means that nonprofits that can effectively engage women will see a boost in giving of both time and money.

While this report offers some great insights into the prosocial behavior of women and men around retirement, there are some unanswered questions. For instance, the findings suggest that nonprofits should absolutely engage both single women and married couples, but the report is less clear on how to engage single men. The volatility in likelihood of giving and giving amount for single men does not appear to be linked to any anxiety surrounding retirement. The report says, “Most of the financial services industry literature finds that men are more confident they will have enough resources to live on during retirement.”

Since what causes the drop in giving from single men right around the transition to retirement is unclear, it is difficult to determine a game plan. However, this study along with past reports indicate that while women give more overall and are consistent, men tend to be “more transactional in their giving, often responding to personal appeals and not engaging as deeply with the organizations they support.” Perhaps a personal appeal or funding for a specific purpose would engage single men during the otherwise volatile giving period surrounding retirement.

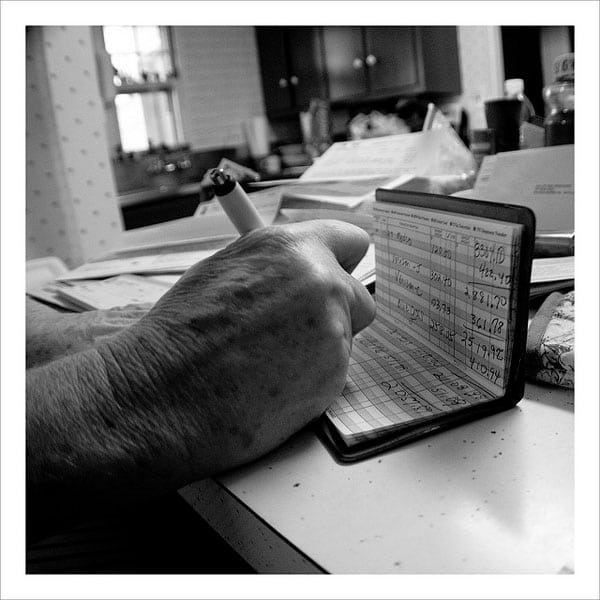

Most blaringly, this report does not discuss planned giving and rather chose to focus on so-called “checkbook” giving or annual gifts throughout retirement. It would be enlightening to understand if and how planned giving impacts annual giving for donors who have already arranged an estate gift or bequest, and if there are gender differences in planned giving.— Sheela Nimishakavi