August 14, 2017; Quartz

The findings from a recently published Rand Corporation Study restate the results of other research from the past half-century with a relatively obvious twist: A thoughtlessly run workplace can also deeply affect the home lives of your employees. That makes sense, since we are talking about whole human beings.

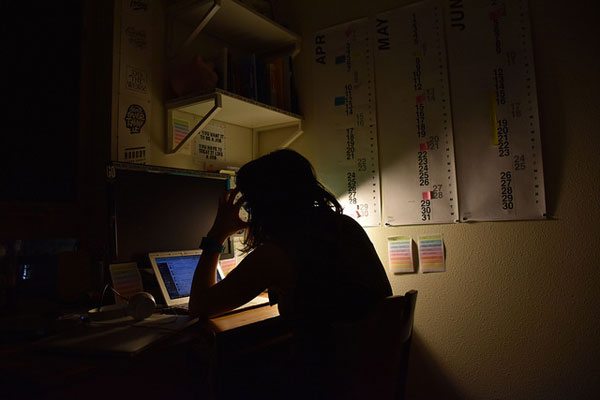

According to Quartz, Nicole Maestas, an associate professor at Harvard Medical School and lead author of “Working Conditions in the United States,” finds in the study “a workplace that is taxing on a lot of dimensions.” In many cases, while work bleeds over into personal time, personal time is still not allowed to bleed over in the other direction which leads to an encroachment into time off that can be problematic, especially for younger workers and women. The study highlights “that American workers are exposed to a high-pressure work environment with consequences for family and social commitments… About one-half of American workers do some work in their free time to meet work demands.”

For many, taking a job means giving up control of time and place.

More than one in three Americans have no control over their work schedules. Another 11 percent can choose between several fixed schedules, while 38 percent can adapt working hours within certain limits. Just 15 percent can fully determine their own schedule…More than one in five non–college-graduate, prime-age workers (defined here as age 35–49) are subject to frequent changes to their work schedule, and more than half of the time, these changes are made with little or no notice.

The inability to control personal time against the demands of one’s job carries some weight with younger workers. The Rand researchers concluded that a “substantial fraction of young American workers feels constrained by their work schedules, presumably because this is a time of intense work effort for them and a period when many have small children. For women, these constraints do not fully resolve with age, perhaps due to ongoing child-rearing demands or the need to assist elderly parents.”

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Further, work is physically demanding.

Nearly three-fourths of Americans report either intense or repetitive physical exertion on the job at least one-quarter of the time…More than one-half of Americans report exposure to unpleasant and potentially hazardous working conditions…A disturbingly high fraction of American workers—nearly one in five—are exposed to a hostile or threatening social environment at work….Most Americans (two-thirds) frequently work at high speeds or under tight deadlines, and one in four perceives that they have too little time to do their job.

The report also cites the benefits of work. One is the opportunity to acquire experience and skills that can lead to better, higher paying employment in the future. The Rand study found that 75 percent of American workers are receiving some form of training from their employer or have elected to get it on their own. But this does not seem to bring confidence that advancement is on the horizon:

Only 38 percent of workers state that their job offers good prospects for advancement. This implies that training does not necessarily correspond to aspirations. And workers, regardless of education, become less optimistic with age, with only about one in four older workers saying that their job offers good prospects for career advancement.

This picture of the workplace spotlights the critical interaction between work life and personal life. Work provides the income necessary for workers to support themselves and their families. For many, it provides access to health insurance and other necessary supports, as well as personal satisfaction and enrichment. But, as Rand has demonstrated, work demands the right to interfere with the non-work part of life. This is where a robust community and social framework is critical to support workers and limit the need to choose between the demands of work and the needs of young children, personal health, or parents. Leaving this tension as a personal challenge to be faced alone by each individual worker will not serve business, worker, or community well in the long run.

But, it also says volumes about what nonprofit employers need to consider when designing their own workplaces, many of which suffer from underfunding and understaffing. As nonprofits, we have a responsibility to understand and respond to the needs of employees. The workplace is full of pressures, especially when it also represents a mission we care deeply about. So, how do we balance that demand with reward? It starts with a more participatory workplace that makes wise use of the human and intellectual capital with which it’s blessed.—Martin Levine