Editors’ note: This article is from NPQ’s winter 2022 issue, “New Narratives for Health.” This is the fifth article of a five-part series, Reclaiming Control: The History and Future of Choice in Our Health, published online by NPQ from July to November 2022, examining how healthcare in the United States has been built on the principle of imposing control over body, mind, and expression. That legacy stands alongside another—that of organizers, healers, and care workers reclaiming control over health at both the individual and systems levels. This article has been further edited for publication here.

Click here to download this article as it appears in the magazine, with accompanying artwork.

As a longtime science-fiction fan and health justice practitioner, I’m drawn to works that imagine the future of our healthcare system. These worlds bustle with technological marvels: lifesaving science that makes immortality attainable, artificial intelligence–controlled diagnostics and treatments, cloned organs (and sometimes cloned humans). They also echo all-too-familiar realities: concierge care available only to the wealthy, paradigm-shifting pandemics, environmental crises, and continued exploitation of communities that already experience the greatest health inequities.

Such realities can feel dystopian, especially when they’ve been with us for centuries. Systems of oppression have produced and are buttressed by mainstream stories about health, bodily autonomy, and choice. Who deserves good health? How is healthcare designed and delivered? What is our individual and collective right to a healthcare system that enables true healing?

Until recently, people seeking to answer these questions worked off of outdated scripts about race, sex, gender, ability, sexual orientation, class, and more. However, organizers, healers, and other change agents have long lifted up counternarratives of health and healthcare. By building power to hold healthcare institutions accountable, designing alternative healing models, decolonizing medical education, and much more, they are imagining health systems that center the wisdom of Black, Brown, and Indigenous communities, generate sustainable abundance for people and the planet, and enshrine people’s right to choose what they seek for their own minds and bodies.

A 2021 brief published by the American Public Health Association, the de Beaumont Foundation, and the National Collaborative for Health Equity highlights our brain’s ability to use stories and images to create meaning and shape what we perceive to be “true, possible, and good. [Narratives] are central to the development of our worldview and the values we hold sacred . . . creat[ing] the scaffolding under which we co-create the systems and structures that govern our lives and influence our access to resources and our collective health and well-being.”1

Transforming our stories, then, is fundamental to creating liberatory systems that center autonomy. Without such transformation, we default to stories we’ve been told. This may be why literature depicts plenty of healthcare dystopias but offers few imaginings of a better way—and even fewer acknowledgments of the rich ancestral healing traditions that existed long before the birth of modern medicine.

Cocreating Stories to Challenge Systems

Shifting our health narratives requires centering a different set of voices. For centuries, the perspectives most listened to in shaping our healthcare system have been those of white, male “experts”—often, clinicians with formal academic training. The result is a narrow set of stories through which to understand what health can or should be.

One example of how a singular story can cause unintended consequences is the body mass index (BMI), which in the twentieth century came to be seen as a key indicator of overall health status. Far from a neutral standard, BMI was developed in the 1800s, when racism was deeply embedded in health science. The standard height and weight that serve as the foundation for BMI assessment were based on an unrepresentative sample of white European men.2 Furthermore, such assessments were never intended to measure individual body fat or health but to serve as a population-level statistic.3 Nonetheless, a person’s BMI can impact the medical advice they receive, their access to treatments, their insurance coverage, and more. This can cause enormous harm, including worsening long-term health outcomes—particularly those of people already facing discrimination in the healthcare system.4

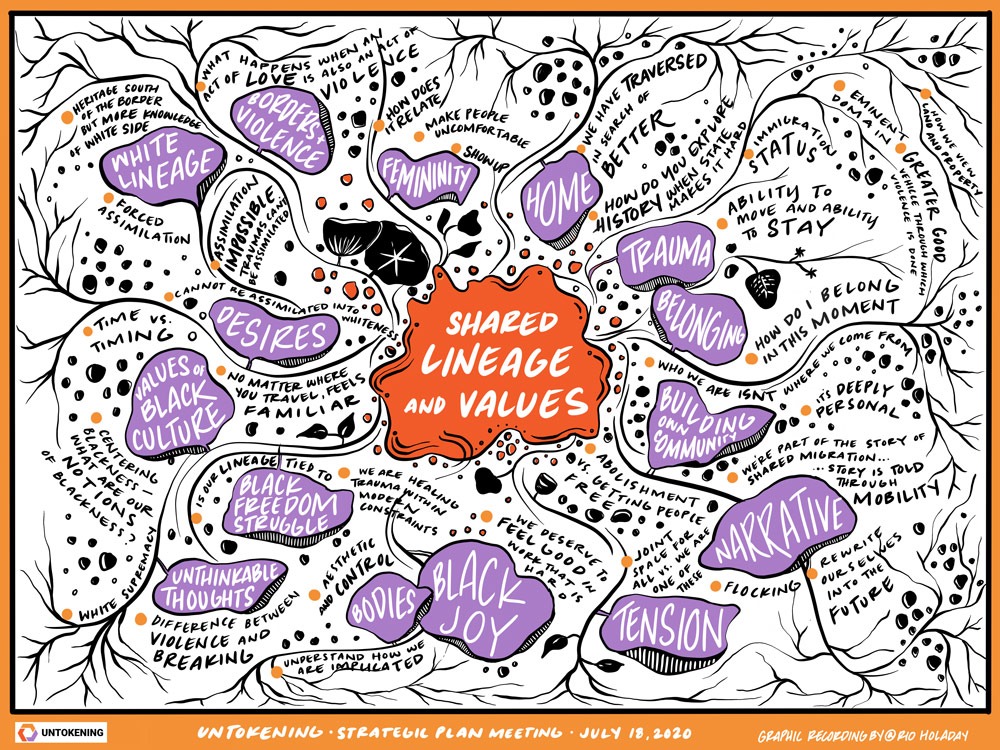

Amplifying the voices of people with diverse lived experiences—including negative experiences with the mainstream healthcare system—is key to shifting our national health narratives. Rio Holaday, a visual practitioner and Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Culture of Health Leader, focuses on such amplification through her graphic recording work with health justice–focused organizations, collectives, and convenings, as well as visual coaching with individuals across the country. Using visuals and words, she draws on her own experiences as a health justice advocate to engage in deep listening and uplift people, themes, and connections that may otherwise go unnoticed. In particular, Holaday explores the necessity of grappling with internal transformation and reflection in order to be an active agent in narrative rather than a passive recipient of it.5

“What are the narratives about how we get to change and liberation? That is often systems work, structures work. It is not, a lot of the time, [about] internal work, nor doing both at once. One [concept] that has always stuck with me and been foundational to my approach is from adrienne maree brown, this idea that we can only create a future as whole as we are,”6 Holaday explains.7 Participants in the graphic recording process often describe feeling heard. Recognizing that those with marginalized identities often face reprisals for stating their opinions, participants have the option to request confidentiality or correct the record. The visual artifacts of these sessions are used to spur further dialogue and are integrated into future justice work.

“Going into graphic recording was a way of asking, ‘How can we shift power? What does it mean to actually listen to people? What does it mean to be listened to, and to feel seen and heard? And how do we capture that in a way that is not just the written word?,’” Holaday shares. “What parts of ourselves as humans are telling the narrative? Typically, it’s the brain, there’s not a lot coming from the body. I’m doing a lot more of: ‘What does this actually feel like?,’ and drawing that.”8

To step beyond our existing models of health, we must also grapple with the values that underlie our healthcare system. The Health Equity Narrative Infrastructure Project,9 an initiative co-led by County Health Rankings & Roadmaps and Human Impact Partners, convened several partners (including health departments and the American Medical Association) from across the country to engage in such exploration. Jonathan Heller, senior equity fellow at the University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute, describes the project’s long-term narrative change goal:

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Our health today and our healthcare system/public health are really impacted by neoliberal worldviews in which the markets need to be free and . . . health is driven by individual behaviors rather than looking at social causes. How do we reveal to folks that we live under these existing narratives and that they impact us in big ways? We’re taking people through this process that is about raising consciousness, having people name their own values and beliefs and come to an understanding that the current narratives are based on a different set of values and beliefs. And then we’re taking people through this process of: based on our stated values and beliefs, what are the stories we want to be telling?10

Building on the work of organizations like the Grassroots Power Project, which recognizes narrative change as one of three faces of power (as named by academic Steven Lukes in the 1970s),11 the project has trained fifty individuals to host political education workshops in their communities, “from the Navajo Nation to the Bronx to the offices of the American Medical Association,” said Heller.12 Based on those workshops, the project developed an integrated health equity narrative that was subsequently shared with workshop participants.

One of the core themes that emerged from this work was that new narratives for health must be built on a set of values that challenge the typical scarcity and profit maximization mindset of existing healthcare structures.

Participants sought out narratives that imagine health systems rooted in values of care, community, and exchange. Another theme focused on the need to bring forward existing emotions, solutions, and stories from movement spaces, including BIPOC-led justice organizations, LGTBQ+ activists, new generations of feminism, disability justice, and more.

Lastly, moving us out of mainstream narratives can also take the form of breaking free from modes of communication favored in healthcare spaces, such as academic journal writing or professional gatherings. In contrast to such communication modes—which tend to establish a hierarchy of expertise that distances the creator from the audience—artists and other cultural influencers have long imagined ways to thrive together, reaching audiences at a visceral level.

SisterSong, a national reproductive justice organization, embodies this approach through its Artists United for Reproductive Justice initiative. “Art has the power to break down barriers, uncover plugged ears, raise new questions and conversations, inspire compassion, spark activism, and rally multitudes around a cause,” the AURJ website states.13 By centering diverse groups of artists working across various mediums, the program supports the development of art that can be easily replicated and shared with movement allies. This culture work serves the dual purpose of bringing together the organization’s members to engage in dialogue and deploying a form of political education and mobilization with people outside the organization.

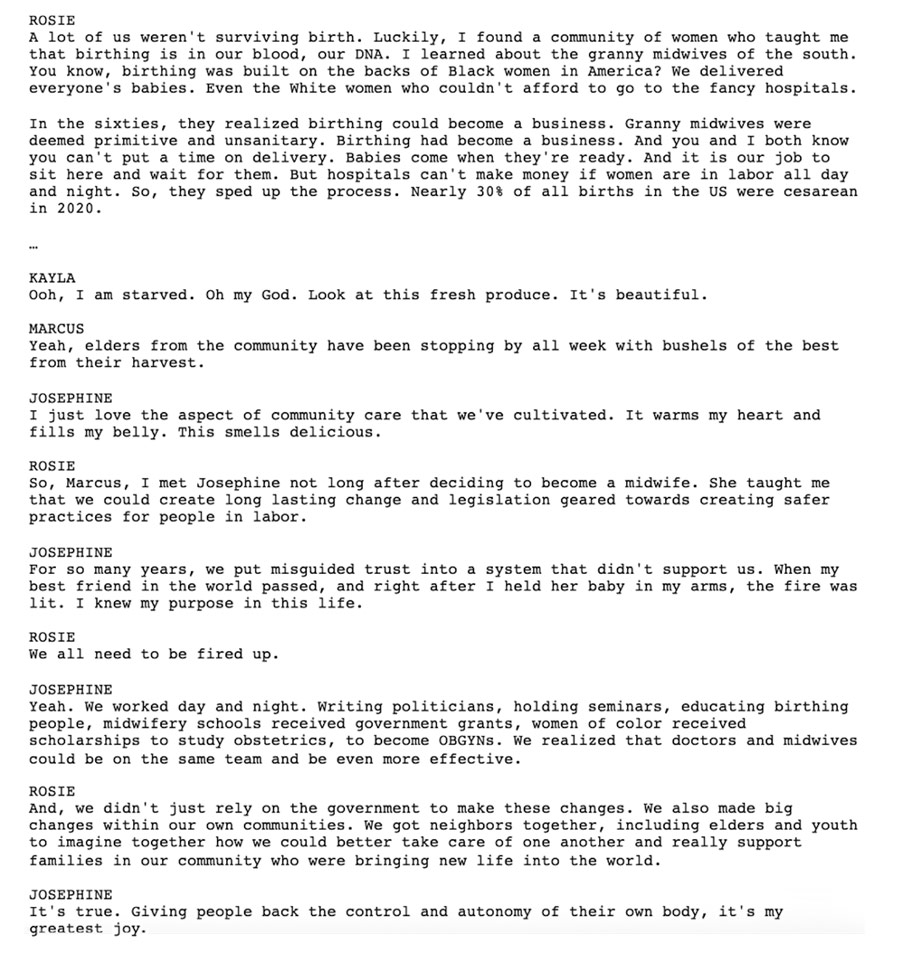

Last year, I had the opportunity to work on The Light Ahead,14 a speculative fiction podcast produced by Beloved Economies and Avalon: Story, that imagines what 2030 might look like if our US economy centered healing and care. Each episode features a vignette informed by dialogue between movement activists and podcast writers. One of my favorite episodes is “Kayla’s Village,” which features Kayla and Marcus, a Black couple preparing for Kayla’s birthing experience.15 They are supported by a midwife named Rosie and by Kayla’s mother, Josephine, who adopted Kayla when her biological mother died during childbirth. Born out of a conversation between Angela Aguilar, a birth worker and codirector of Movement Generation, and writer Jacquelyn Revere, the episode envisions holistic communal support for birthing people rooted in the rituals, knowledge, and care that oppressed communities often already deploy to support one another through life’s challenges.

“Kayla’s Village” demonstrates how new visions for health are in many ways based in the ancestral practices of BIPOC communities. These practices, which have survived despite racial capitalism’s attempts to eliminate them, are rooted in values of respect, dignity, and connectedness to one another and the land, while still honoring individual choice and autonomy.

***

We need new narratives to push the boundaries of what health can be in this country and to challenge mainstream narratives, whose ongoing power is reflected in the Supreme Court’s recent stripping away of reproductive rights and in ongoing structural racism and economic exploitation. Highlighting the stories of movement organizations, grassroots entities, and healing practitioners of all backgrounds offers us a different set of dreams to reclaim bodily control from the state, the healthcare industry, and other oppressive systems.

Notes

- Narrative Change: Policy and Practice Brief (Washington, DC: American Public Health Association; Bethesda, MD: de Beaumont Foundation; and Washington, DC: National Collaborative for Health Equity, October 2021), 1.

- Your Fat Friend, “The Bizarre and Racist History of the BMI,” October 15, 2019, Elemental, elemental.medium.com/the-bizarre-and-racist-history-of-the-bmi-7d8dc2aa33bb.

- Sylvia Karasu, “Adolphe Quetelet and the Evolution of Body Mass Index (BMI),” Psychology Today, March 18, 2016, www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/the-gravity-weight/201603/adolphe-quetelet-and-the-evolution-body-mass-index-bmi.

- Carly Stern, “Why BMI is a flawed health standard, especially for people of color,” Washington Post, May 5, 2021, washingtonpost.com/lifestyle/wellness/healthy-bmi-obesity-race-/2021/05/04/655390f0-ad0d-11eb-acd3-24b44a57093a_story.html.

- Rio Holaday, “Portfolio,” rioholaday.com/portfolio.

- Amisha Ghadiali, “adrienne maree brown on Future Visioning, Layered Time and Grief // Microcosms of Liberation, Justice and Pleasure,” April 7, 2022, all that we are, podcast, episode E146, 1:01:11, allthatweare.org/2022/04/07/e146-adrienne-maree-brown-on-future-visioning-layered-time-and-grief-microcosms-of-liberation-justice-and-pleasure/.

- Rio Holaday, interview with the author, October 10, 2022.

- Ibid.

- Joanne Lee, “The Power of Narrative: Bringing People Together to Advance Equity with Jonathan Heller,” Our Blog, Healthy Places by Design, March 23, 2022, healthyplacesbydesign.org/the-power-of-narrative-bringing-people-together-to-advance-equity/.

- Jonathan Heller, interview with the author, October 10, 2022.

- Richard Healey and Sandra Hinson, “The Three Faces of Power,” Grassroots Power Project, November 24, 2013, grassrootspowerproject.org/analysis/the-three-faces-of-power/.

- Heller, interview with the

- “Artists United for Reproductive Justice,” SisterSong, accessed November 8, 2022, sistersong.net/ artist-united-for-reproductive-justice.

- The Light Ahead, Beloved Economies and Avalon: Story, belovedeconomies.org/about-the-light-ahead-podcast.

- “Kayla’s Village,” The Light Ahead, podcast, episode 6, belovedeconomies.org/podcast-episodes/episode-6.