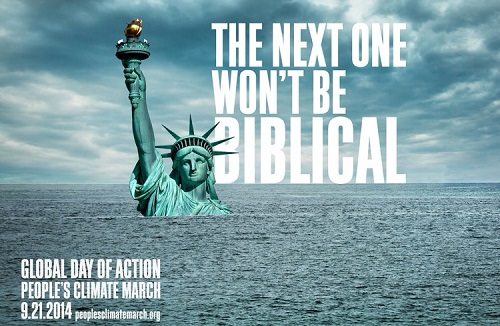

Image Source: PeoplesClimate.org

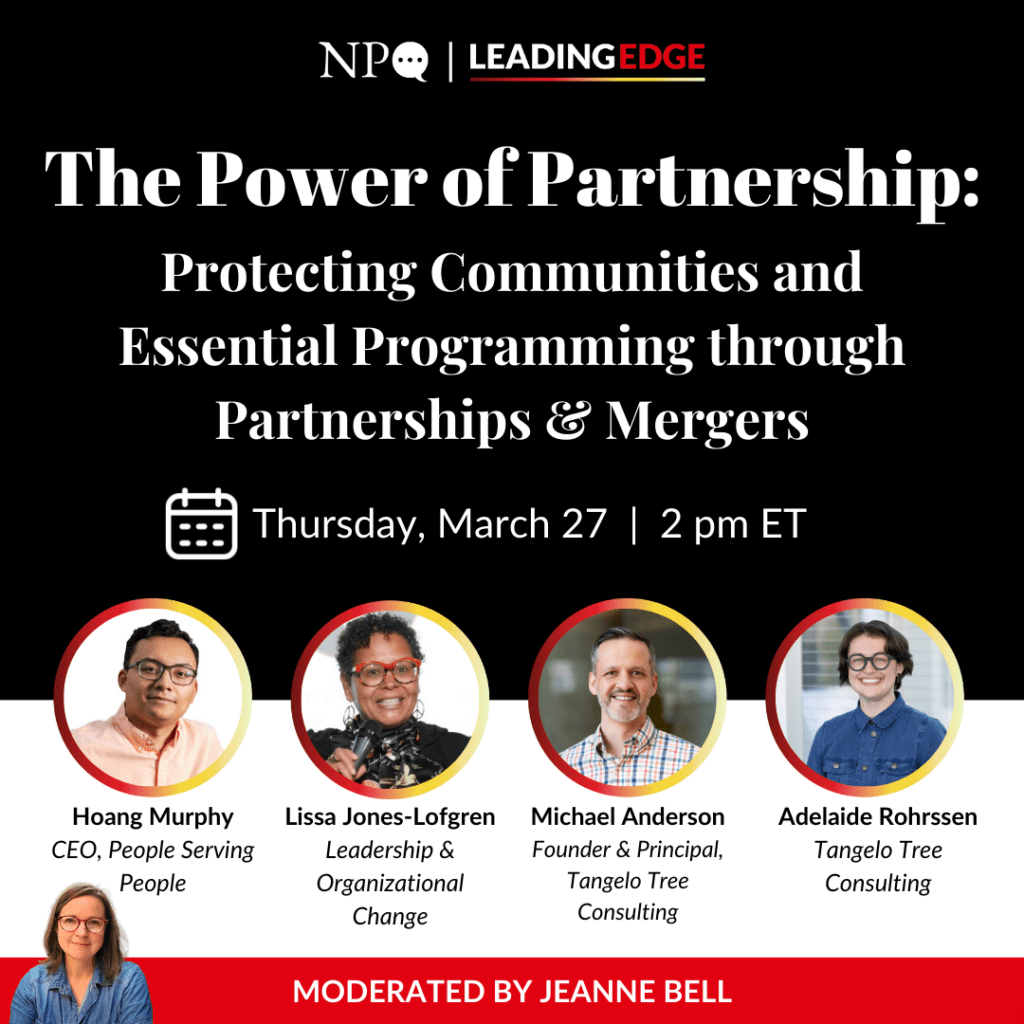

Naomi Klein, the author of No Labels and, more recently, of This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs. the Climate, has been widely quoted in the press concerning the recent massive climate marches around the world, but she spotted a troubling dimension of corporate involvement in a march that criticized the excesses of corporations and capitalism. Klein has been chided for the failure of her most recent book, This Changes Everything to acknowledge and credit the laudable activity of corporations that are investing in renewable energy and reducing their negative environmental impacts. A particularly strident critique was published in Slate. Zachary Karabell wrote:

“Capitalism—in the form of multinational corporations—is doing more than many governments and multilateral institutions to stem the progression of climate change. They are doing so because of self-interest, not altruism; the relentless demand for profit is compelling an increasing percentage of the world’s largest companies to take concerted, forceful action. Yes, many companies remain obstacles to action, as Klein argues, but increasingly, more are becoming the agents of rapid and necessary change.”

Klein responded that corporate efforts do exist and some are quite promising, but the individual efforts of environmentally conscious corporations do not add up to a sufficient response to the problems of climate change. Nor do they promise a solution for the future, and not simply because of how small these efforts might be cumulatively compared to the climate-changing actions of most corporations:

“It’s easy to mistake a thriving private market in green energy for a credible climate action plan, but, though related, they are not the same thing. It’s entirely possible to have a booming market in renewables, with a whole new generation of solar and wind entrepreneurs growing very wealthy—and for our countries to still fall far short of lowering emissions in line with science in the brief time we have left. To be sure of hitting those tough targets, we need systems that are more reliable than boom-and-bust private markets.”

The climate march revealed a surprising and somewhat disconcerting connection to the corporate world. Klein strongly advocated the position that climate change cannot be successfully addressed within a framework of largely deregulated capitalism. At a minimum, she suggested that the kind of regulation associated with European nations with social democratic governments that are “are willing to intervene in these ways and protect the public sphere and that green transition” is necessary. Among a segment of the climate change marchers, including those who showed up the day after the official march to #FloodWallStreet in homage of the Occupy movement, there was a strong belief that capitalism per se, whether regulated or not, is the problem and must be undone to protect the planet.

This apparent contradiction between the usefulness of the corporate world in combatting climate change and the responsibility of capitalism for having created and exacerbated the environmental problem was actually evident in overt and covert corporate roles in the climate march.

A number of corporations have been identified in the press as official and visible sponsors of Climate Week, particularly Lockheed Martin. A major defense contractor isn’t typically thought of as an environmental advocate, given the disastrous climate impacts of military products, but Lockheed Martin is making strong efforts to promote its commitment to environmental sustainability. At almost the same time as the climate march, Lockheed Martin was added to the Dow Jones Sustainability Index, containing roughly 2,500 of the world’s largest companies. (The list of all of the North American companies on the index is here.)

Other sources paint a somewhat less environmental-friendly picture of Lockheed Martin, including the Corporate Research Project’s review of Lockheed’s various violations of environmental and other standards. Among them are charges of “environmental racism” lodged against the company by residents of Manatee County in Florida for failing to notify residents about toxic beryllium leaking into the groundwater and water wells and Lockheed’s litigation against the federal government to get taxpayers rather than the company to pay for environmental cleanups where Lockheed tested military and space rockets. (The U.S. District Court ruled in 2014 that for past cleanups at three facilities, the U.S. government would have zero liability and Lockheed 100 percent liability, and for future cleanups at the three sites, liability would be between 19 to 29 percent for the U.S. government and between 71 and 81 percent for Lockheed, depending on the site.)

Regardless of Lockheed’s specific environmental track record, one must still account for the presence of one of the nation’s largest corporations and the largest of all defense contractors in terms of revenues received from U.S. government contracts a a climate march sponsor.Did climate marchers and march supporters realize that Lockheed and other major corporations were sponsoring, presumably with financial contributions, the climate change protests? To convene, organize, and manage a protest march of hundreds of thousands of people takes money. It would be naïve to imagine that this kind of event would be purely volunteer-based and –financed, though perhaps people might have assumed that march expenses were covered by philanthropic grants, individual contributions, and perhaps fundraising through crowdfunding. But some elements of the march costs struck some otherwise supportive observers as questionable.

For example, critic Aron Gupta noted that the climate march spent $220,000 on advertising in the New York subway system, an unusual expenditure for a grassroots protest. Writing for Counterpunch, Gupta notes that the organizers of the climate march were open to contributions and participation from anyone, without preconditions. The subway ads were one mechanism of attracting widespread support for the march, even from bankers who might be riding the Lexington Avenue subway line to Wall Street. Without identifying his sources, Gupta wrote, “organizers admitted encouraging bankers to march was like saying Blackwater mercenaries should join an antiwar protest.” Although he was a participant in the march, Gupta admitted misgivings. “Having worked on Madison Avenue for nearly a decade, I can smell a P.R. and marketing campaign a mile away. That’s what the People’s Climate March looks to be.”

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

The Caracas-based teleSUR multimedia company reported that another military contractor, Atlantis Resources Ltd., was also a climate march sponsor. The Singapore-based Atlantis actually describes itself as a strategic partner of Lockheed’s on a variety of technology development projects, including tidal power systems—that is, focusing on clean energy from waves and tides. Does it matter that big corporations were signing on to the climate march or among the march’s major organizing groups?

Former New York Times correspondent Chris Hedges excoriated the march as “the last gasp of climate change liberals” because of the participation of activist groups that he characterized as “little more than corporate fronts.” He took particular aim at The Climate Group, which, he charged, gets support from BP, Dow Chemical, Duke Energy, Goldman Sachs, HSBC, and JPMorgan Chase. Hedges is clearly not supportive of the open-invitation approach of the climate march organizers, questioning whether corporate sponsors are legitimate players in a grassroots mobilization to fight climate change. “Our democracy is an elaborate public relations charade. And the longer we accept this charade the longer we will be irrelevant. Only when we understand power can we fight it,” Hedges wrote for Truthdig. “This fight must be waged on two fronts. We must disrupt the machinery of corporate capitalism and at the same time build parallel, autonomous structures for self-governance that address basic needs such as food and green energy.”

Among the variety of corporations listed on the Climate Week NYC webpage, each presented with a “visit us” button, are as follows:

- Partners and sponsors: Swiss Re (one of the world’s largest reinsurers, self-described as “greenhouse gas neutral since 2003”); Lockheed Martin; BT (telecommunications); BMW (which manufactures BMW and Rolls Royce automobiles); HP (which says that its “integrated approach to business, HP Living Progress, is about creating a better future for everyone through our actions and innovations…to solve society’s toughest challenges”); Bloomberg; CBRE (headquartered in Los Angeles, the world’s largest commercial real estate services firm); and, among nonprofits, the Rockefeller Brothers Fund, which recently announced a major asset divestment from coal, and the Climate Group.

- “Clean revolution partners”: Philips (electronics); IKEA; and non-business entities such as the province of Quebec, the Prince Albert II of Monaco Foundation, Zennström Philanthropies, and the World Bank.

Our sympathies are on both sides of this debate, it seems. On one hand, it is highly unlikely that some of these corporate sponsors are volunteering for tougher governmental regulation on environmental and other issues. Lockheed, for example, was the 14th-ranking lobbying entity in the nation in 2012 and 2014 and made campaign contributions to politicians known for being none too friendly to environmental issues, such as Senator John Cornyn (R-TX), Rep. Kay Granger (R-TX), Rep. Rodney Frelinghuysen (R-NJ), Rep. Mac Thornberry (R-TX), and Rep. Buck McKeon (R-CA), though the corporation hedged its bets and gave six-figure donations to both the Romney and Obama campaigns in 2012. It’s difficult to imagine U.S. corporations like Lockheed Martin and others sponsoring the climate march and its organizers opening the door to corporate regulations akin to those in use in much of the European Union without effective grassroots mobilization across the country. The climate march may engender a political campaign for those kinds of corporate regulations, but onlyso long as march advocates translate their climate change concerns into specific demands for tough governmental regulation on corporations and their carbon footprints. Corporate sponsors may have wanted to participate in the pro-environmental feeling of the climate change march, but might not have been so generous with their support had the march announced tough, explicit demands for government oversight.

On the other hand, the kind of Occupy-like advocacy suggested by Gupta and Hedges is necessary to keep the climate movement on target with the regulatory oversight that is so desperately needed. If major profit-making corporations have added their money and influence to the climate movement, one likely impact might be a softening of advocates’ demands for needed regulatory oversight. Strident activism by the Flood Wall Street segment of climate marchers, who may be drawing inspiration from the Occupy playbook, serves as a counterweight to the increasing corporate influence in the climate movement. The UN’s Climate Summit, convened by Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon, announced $200 billion in financial commitments to be realized by the end of 2015, including money for the Green Climate Fund’s strategy of decarbonization of investment portfolios, but much of the strategy relies on corporate participation and follow-through, such as Kellogg’s, McDonald’s, and Wal-Mart committing to increasing the amounts of food they produce with “climate-smart approaches”; Saudi Aramco, PEMEX, and TOTAL, among others, committing to share best practices and “catalyze meaningful action on climate change”; and Deutsche Post, DHL and IKEA pledging to work toward cleaner freight delivery (“green freight”).

Powerful advocacy is necessary to ensure corporations, governments, and international bodies make their commitments more than lip service. But a revolutionary movement of anti-capitalists is not going to undo climate change. The movement has to be a combination of voluntary movement, government regulation, community mobilization, and nonprofit advocacy, but dealing with the reality that a repeat of Occupy might not do much more on climate change than Occupy itself did to rein in the excesses of Wall Street.

Klein’s comments, however, spur thinking about another dimension of the frailty of voluntary business solutions to climate change. The subway ads were explicitly meant to generate commercially attractive designs that would attract attention from audiences that aren’t likely to immediately connect with or be responsive to climate change messages. Communicating the climate change argument to a wider audience is necessary, and posters like this one from Ellie and Akira Ohiso are important to communicate messages to the public. But for many, the need to appeal to a broad swath of the public meant the climate march was feel-good and inclusive, but made so through a lack of divisive demands that might have turned off some part of the wide array of supporters, from anti-capitalist marchers to corporate underwriters. One ad read, “What puts bankers and hipsters in the same march?”, with Avaaz’s campaign director, Ian Keigh, explaining that “bankers and hipsters are the first two demographics that spring to mind when people think of New York”—a rather myopic view of New York City’s population.

The result was that the feeling of the march, according to Brooklyn writer Peter Rugh who was on the original organizing committee behind the event, was a “general effect of…de-politicization in favor of creating a big tent.” Rugh concluded, “I don’t see the point of demonstrating unity when there is no clear, cohesive purpose other than to raise awareness or show we care.”

Still, there was an underlying unifying scheme, one of “greenwashing.” The need to maintain a big tent meant that social enterprise-like business partners of the march, including Peace Coffee, EcoCommode, Creative Footprints, Solar Cooker, SunHarvest Solar, and Range West, combined with the big corporations that issue glossy corporate social responsibility and sustainability reports to create a greenwashed view of the business sector. It is greenwashing the corporate sector when businesses get to advertise themselves as implementing and promoting business practices that minimize deleterious environmental impacts when their actual environmentally sensitive practices might be relatively minor and inconsequential compared to their overall business operations.

The corporate world looks good from the participation of EcoCommode and Lockheed Martin in the midst of hundreds of thousands of climate marchers. But, assuming that Lockheed and the other big corporations behind the march really are taking positive steps toward decarbonizing their manufacturing and marketing activities, the reality is that those efforts are still but a sliver of what the corporate world is doing about—or to—the environment. If the climate march is going to progress from painting hipsters, bankers, social enterprises, and big corporations with a green hue, the movement is going to have to get tough with demands for a substantive regulatory regime that makes green a mandatory color for capitalism.