Enterprise: a project or undertaking that is especially difficult, complicated, or risky.

(Merriam-Webster Dictionary)

The field of digital news sites based in nonprofits is very new and experimental, but it now has a base of invaluable information that other fields might give their eyeteeth for. Specifically, the Knight Foundation has today released a report that lays out the state of enterprise in 18 such sites, all but one of which are relatively new. This provides an early sense of the patterns in the development of various kinds of endeavors. It allows such sites to compare themselves against their peers and to target those from whom they think they may be able to learn. In all of that, it is an enormous gift to this emerging field. Philanthropy in other fields should think about the need for such practically useful information.

The report examines nonprofit-based news sites across three categories: local, state and national. It compares the sizes of their readership communities as measured through web traffic (page 11) and budgets and staffs (page 6), and correlates those to the revenue mixes in the various organizations. It looks at rates of revenue growth and uses of strategies. It digs down into some interesting details, such as how one organization gained Twitter followers at a fairly fast clip, but stays sufficiently at the balcony level to provide a snapshot of a field in flux.

The whole report is well worth reading, but NPQ also talked with two of those involved with the development of the publication—Mayur Patel, Knight’s V.P. of Strategy and Assessment, and Michael Maness, V.P. of Journalism and Media Innovation—to get a comprehensive sense of the trajectory of the field in enterprise terms. Maness led off with the observation that those sites that had started on the early end realized quickly that revenue diversity would be an issue. Many would need a “garden of revenue,” but it was as yet unclear what would take root and flourish over time in the new news landscape.

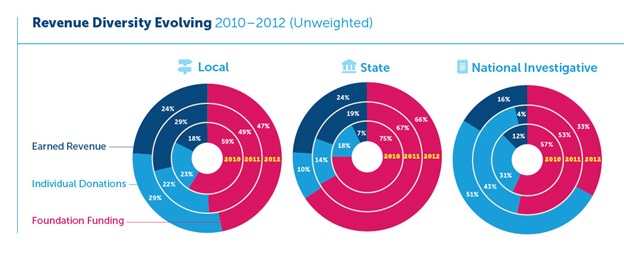

I asked Patel about what was generally apparent in terms of the evolution of these sites over the three years they watched them, and he said there were basically two routes taken to work out of an overreliance on foundations, which were not expected to provide ongoing operating money. He said the first path was to increase their pushes around individual donations. He added that across all 18 organizations, they saw the number of individual donations double from 4,000 to 8,000 over a three-year period. “Some of these donations were from high net worth individuals, but many were much smaller.” The second route, he said, was to make “a significant play around corporate sponsorships and events.” Some groups did both. The report contains interesting graphics that show the reader the evolution of proportions of revenue over time in the three categories and for individual sites.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

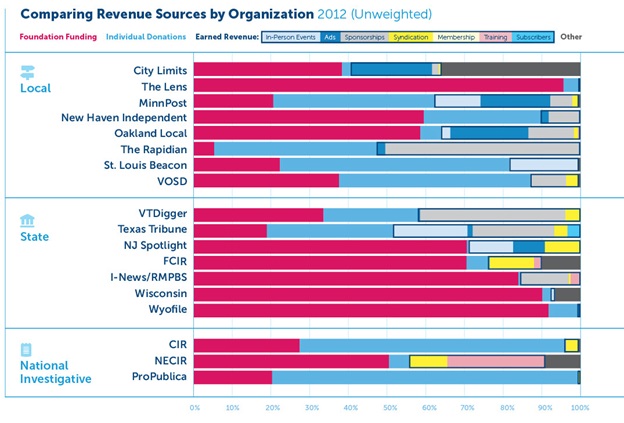

The graph on page 28 of the report (reprinted above) shows revenue diversity on the sites, and there is no question that revenue diversity is higher in most of the small organizations than in the two largest, ProPublica and the Center for Investigative Reporting, both of which have annual budgets of more than $10 million and whose revenue is dominated by individual donor money and foundation funding. (See the graph from page 29 of the report below.)

But these two are also well-capitalized sites where investigative work is their stock in trade. I asked Michael Maness about the lopsidedness of the picture, and he explained, “The large organizations had big donors to start with, and the size of that category may be hiding some of the smaller categories of developing sources, but big infusions of money at the start meant that these orgs were built in a way that did not cause them to have to scramble as much. Many of the larger ones made sure that they had run rates of three to five years when they started, from foundations as well as high net worth individuals, but the others really had to bootstrap their way up. Scarcity is the entrepreneur’s advantage. You’d expect the ones that were bootstrapping to grow diversity faster because they had a smaller window of feasibility.”

Patel chimed in to talk about the differences between the top two in terms of budget size contrasted with the Texas Tribune, which has an annual budget less than half that size, but still far larger than the others in the study. The Texas Tribune was started with an investment that was time-limited, and it has spent its money on trying very quickly to build its community of readers, its engagement with them, and its diversity of renewable revenue. Patel says that this points out the difference between the two enterprise approaches. “Looking at CIR and ProPublica, they are significantly larger than the other entities, but their overall revenue mix doesn’t necessarily have the same amounts of money from earned revenue sources, like events and sponsorships, as the Texas Tribune has, and we are not necessarily ever expecting it to look like that because ProPublica is a national investigative play, and what we have started to see is a move on their part from foundations to individual donors. People make two different plays on this—individual donors, and a mix of donor work and other more diverse sources.”

Both mentioned that one area where non-investigative sites are concentrating is the engagement and participation of communities of readers. Maness said that the need for public participation in local information economies is becoming ever more apparent, and that there is a connection between engagement and cash donations, saying, “We know from Kickstarter that when people give money, they pay attention to it.” Patel added that a big question right now for the field is, “Can the end user, who is the final beneficiary, be convinced to contribute? Not only is that important for the business model, it may well lead to better engagement, better impact, and better journalism.”

But even given those differences, Maness and Patel emphasized that, for either type, the ways in which working capital is spent—if not spent only on content—can allow sites to get ahead of the game. Using it to hire technology talent, for instance, can pay dividends in the long run if we think about capital as an infusion of equity, not operating cash.

I asked Maness and Patel about the study published in NPQ that showed that youth organizations got larger by focusing on fewer revenue sources, and asked if they saw any correlation to journalism organizations, given the picture we see. Maness responded with an emphatic no. “We need diversity now in part because I am not at all sure that now is the time for focused consolidation. So many of these revenue models are still to be experimented with, and we really do not know exactly how you build the corporate sponsorship model in perfect execution.”

The market for new journalism is changing in the broadest sense of the word, and so are the interactions between journalism sites, at least those who do not focus overly exclusively on investigative work and the market of end users.

In the end, Maness said, the issues in this space are not all that different from those in large media organizations, in that they have to handle the continuous disruption of the space. Nonprofit journalism sites, some of which are quite lean and small, he said, “have to see themselves as engines and drivers of change, shifting with the audience…. It took a hundred years to adjust to movable type. Adoption rates of emergent technologies, breathtakingly faster and faster, so just when it feels like we have arrived somewhere, it shifts. Nothing suggests that any of those cycles are diminishing.”

Patel agrees saying that he predicts that the whole field will progressively move “further from developing and publishing content and displaying it to thinking about how to build a unique set of services and experiences for individuals, and I wouldn’t be surprised to see donor databases and content management systems integrated to provide a more tailored product.”

The recommendations at the end of the report are fascinating and useful for far more types of organizations than simply the journalism sites. Here are the bullet points:

- Attack your assumptions always

- Pursue the greatest overlap between niche and need

- Provide services don’t just publish

- Invest beyond content

- Measure what matters

- Strive for diversity of funding

- Bolster the brand by building partnerships

- Move to where your audience is