August 30, 2012; Source: BusinessWeek

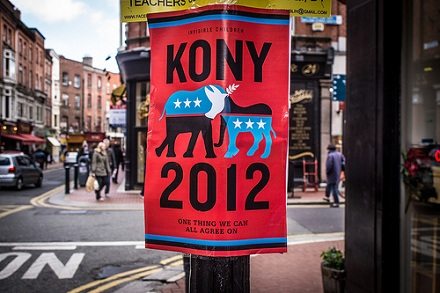

Whatever happened to Kony 2012? There was something unsettling about the details of the campaign that emerged last spring, as much of the world became captivated by the most famous viral video ever. The sad story about the public breakdown of Invisible Children co-founder Jason Russell, who is still under treatment for his psychotic episode and has not returned to his job, captured attention, but much more important is the fact that, in Central Africa, Kony and the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) are still operating, reportedly focusing on a portion of the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

If the Kony 2012 video (seen by 85 million people on YouTube and 17.5 million on Vimeo) was to make Joseph Kony famous, it succeeded, but the result hasn’t stopped Kony’s run. In response to the publicity, President Obama (who endorsed the video) sent 100 Special Forces members to Uganda to track the LRA. During a visit with Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni last month, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton hinted at the use of drones to flush Kony out from his jungle coverage. However, Secretary Clinton was in Uganda primarily to get Uganda and Rwanda to stop aid (which they denied they were providing) to the Tutsi-led M23 insurgents that are fighting against the Congolese troops of President Joseph Kabila.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

As horrendous as Kony is—and he is a version of humanity that is hard to contemplate, prone to recruiting children as soldiers, raping women and girls, and mutilating opponents—Kony has been a minor character in the region for some time even before the Kony 2012 video, and as Clinton’s realpolitik visit showed, Kony is not considered a high priority. By most press accounts, Clinton chuckled when she talked about supplying drones to hunt Kony.

Kony is still scurrying under the jungle canopy with his small army, but Invisible Children has changed. It was already a growing operation, capturing the $1 million Chase Community Giving prize in 2010 and reaching $13.7 in revenues as of 2011. Although the in-person turnout of people for the group’s “Cover the Night” event was tiny, the donations from the Internet viewers of the Kony 2012 video will likely result in a tripling of Invisible Children’s income when its 2012 numbers are released.

In a recent article, BusinessWeek examines the implications of the Invisible Children marketing campaign, which was light on the facts (not mentioning that Kony hadn’t been seen in Uganda since 2006), sharp on ideas about how to be noticed (shortening the time of the Kony 2012 film to 29 minutes, 59 seconds, because a timestamp starting with a two turns off less people than one starting with a three), and a little self-indulgent (Russell listed his young son in the credits as the film’s “director of idea development”). Invisible Children plans a “global dance party” as its public relations event for 2013. There are big questions about Invisible Children’s finances, questions about how it is using the money it received to stop Kony, questions about the focus on Kony rather than a broader array of official and more powerful thugs operating in that area of the continent, and its evangelistic roots and politics.

Invisible Children’s value should be the outcome of its program, but in the real world, Invisible Children’s success is its marketing and fundraising. Another BusinessWeek article quotes the vice president of the Muscular Dystrophy Association, which is now getting ready to run its first telethon without Jerry Lewis, admitting “promotion envy” in regards to Kony 2012. While Invisible Children does have some programs in Africa, the organization’s measure of success appears to be much more focused on its Millennial fundraising triumph. –Rick Cohen