Judy Michaels1 starts each morning with a clear vision of the day’s agenda: making calls to bring in some new and much-needed dollars, having a “quick” conversation with a board member’s recent college-graduate niece asking for potential job options in the sector, persuading a funder to increase the foundation’s support for a key program, making another call to a funder on a renewal proposal due in two weeks, attending a management meeting to review program and budget priorities, calling the organization’s legal counsel on a potential discrimination lawsuit. For this executive director of a midsized multiservice nonprofit with a budget of $4.2 million and a staff of 105, it will be another long, challenging, and stressful day. Before she even gets to her desk, the day will be derailed by other priorities. At 8:00 a.m., she placates an irate neighbor whose car fell victim to debris left by a construction crew renovating the neighborhoood day care center. At 8:20, a dissatisfied client waylays her at the coffee shop with complaints about advice received from a staff person. At 8:35, she makes a mental note to speak to maintenance about increasing the cleaning staff’s shift time because the beautiful fall leaves have littered the building’s steps and become a liability. As she heads through the front door, she is treated to an angry rant from the membership coordinator who supervises a persistently late employee.

This week it’s urgent to get a permit to convert a recently acquired building into supportive housing for seniors. She will have to convince a city councilman to flex some muscles on her behalf, the foundation officer to approve funding to complete the prelicensing requirements, and the neighbors to tolerate the construction hassles for six months. And it’s only Monday.

Such are the challenges of nonprofit leaders wrestling with the complexities of achieving sustainability and growth. Contrary to intuition, the smaller the nonprofit, the more intense the executive’s role. The patterns of relationships are condensed among fewer people who may have less clearly defined roles. Despite the stresses, amazing individuals with incredible skills rise to the task each year to lead organizations with important missions, driven by not much more than a passion to help others. What we know is that only the best and the brightest executive directors can survive.

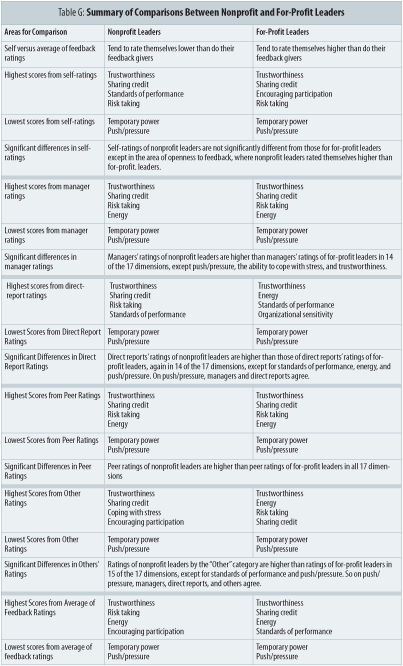

With such hurdles to overcome, the dramatic finding that nonprofit leaders scored higher than for-profit leaders on leadership practices may not be surprising. Nonetheless, the often unspoken but pervasive belief is that the for-profit sector produces better executives. But is there any truth in this belief?

A study conducted by Community Resource Exchange (CRE), a nonprofit social-change consulting firm, and Performance Programs Inc. (PPI), a consulting firm that specializes in leadership and organizational assessment, showed that nonprofit leaders received higher ratings than for-profit leaders based on feedback from direct reports, managers, peers, and a category called “others.” The purpose of this article is to explore those findings and derive some important lessons for nonprofit boards of directors and others responsible for hiring and managing leaders of nonprofit organizations.

Leadership in for-profit endeavors is widely studied; the same is not necessarily true for nonprofits, particularly not for community-based organizations. CRE’s Leadership Practice uses the 360-degree feedback method in its leadership caucus, a nine-month leadership development program that also focuses on coaching and team building. Between 2002 and 2006, CRE partnered with PPI to develop sector-relevant norms for nonprofit leadership practices. CRE chose the 360-degree feedback survey known as the Survey of Leadership Practices (SLP). This survey was researched and published by the Clark Wilson Group and used extensively by the staff at PPI in its assessment work.

The 360-degree feedback technique is considered to be an effective leadership development tool because it focuses on assessing skills that are relevant to the leader’s role, that can be seen by others, and that are responsive to development efforts. Coupled with coaching, the method helps leaders increase their competencies by illustrating how others perceive their effectiveness. Typically, there is a self-assessment as well as feedback from the manager, direct reports, peers, and other individuals. In the nonprofit setting, the board chair often provides feedback as well as managers, peers, leaders of other organizations, colleagues, members of the board, and funders.

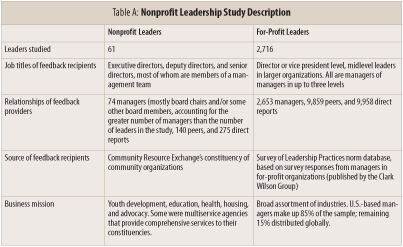

SLP has 85 questions that measure 12 core leadership skills and provides an overall judgment of a leader’s impact, power and influence. (SLP is further described in Appendix A.) The nonprofit and for-profit groups were compared using an analysis of variance with post hoc comparisons. Table A describes the two populations used for the study.

The results of this study are a twofold bonanza. First, as originally intended, we now have an appropriate point of comparison for nonprofit leaders’ leadership practices.

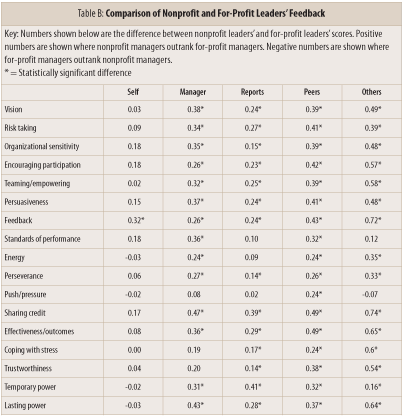

Second is the view of nonprofit leaders as provided by managers, direct reports, peers, and others. When rated by their own managers, peers, and direct reports, nonprofit leaders outscored their for-profit counterparts (alpha is > 0.05, which means that there is only a 5 percent chance that the higher ratings of nonprofit leaders compared to for-profit leaders is a fluke). This finding is all the more notable because nonprofit leaders outscored for-profit leaders in 14 out of the 17 dimensions of leadership practices (see Table B). If they scored higher in only 60 percent rather than 82 percent of the dimensions, it would still challenge the prevailing thinking on leadership. While it is premature to declare that nonprofit leaders are more effective, the findings call conventional wisdom into question. The challenge now is to examine the findings more closely and to consider the implications for leadership development in the nonprofit sector.

Nonprofit leaders showed significantly higher ratings than for-profit leaders in 14 out of 17 leadership dimensions from all groups providing feedback. Of the 14 dimensions in which nonprofit leaders outscored their for-profit counterparts, the most dramatic differences between nonprofit and for-profit leaders appeared in six dimensions that include skills similar to those often included in discussions of emotional intelligence (which are denoted by an asterix in Table C). These dimensions are characterized by sensitivity to people and situations and the use of personal versus hierarchical power.

Nonprofit leaders scored lower compared with for-profit leaders in only three of 17 dimensions (see Table D).

Areas where nonprofit leaders scored low are worth examining more closely. The first area is “push/pressure,” which is defined as pushing for results and applying pressure on others until a task is successful. The findings for this area should be interpreted in light of its context. A certain amount of pressure and energy works best depending on the situation. But that said, nonprofit leaders may not exert enough pressure and energy to get the desired results, and they tend to have difficulty coping with stressful situations.

Nonprofit leaders also rated lower on energy level. Energy is defined as demonstrating a desire to achieve results quickly. Based on PPI’s other leadership studies, energy is often revealed as the tangible component of charisma. Nonprofit leaders may exhibit less energy externally or be less conscious of time than their for-profit counterparts.

Nonprofit leaders also scored low in terms of their ability to cope with stress, which is defined as maintaining command control, managing difficult situations calmly, and handling unforeseen trouble with confidence. These low scores are corroborated by another study finding, discussed later in the section on leaders’ self-assessments, in which nonprofit managers consistently rated themselves lower than did those providing feedback. It seems that the nonprofit executive may suffer from self-doubt.

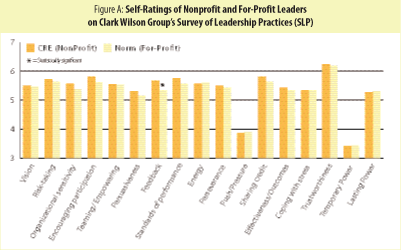

When we look more closely at the self-ratings of the two sample groups, nonprofit leaders do not see themselves very differently from for-profit leaders (see Figure A). Only on the feedback dimension—in terms of being open to implementation issues, paying attention to the reactions of others, and being responsive to suggestions—do they see themselves as more skilled than do their for-profit counterparts. Considering the multiple stakeholders—board members, funders, community leaders, policy makers, clients, management teams, staff—whose input nonprofit leaders must consider on a daily basis, this is not surprising. Stakeholder input is so intertwined with nonprofit leaders’ daily activities that they have learned to deal with it.

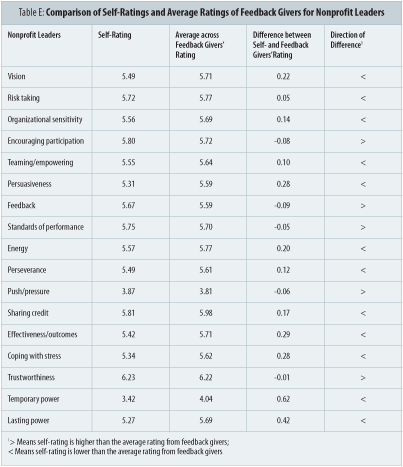

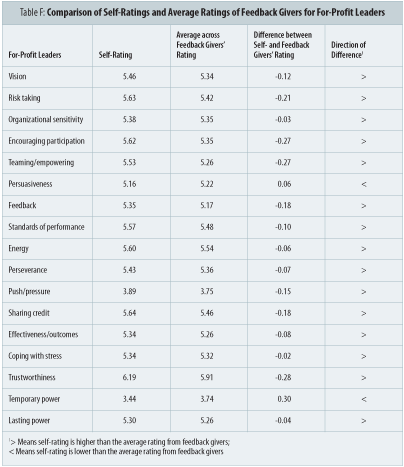

When we compare self-ratings with those of feedback givers, interesting differences surface as well. As noted previously, nonprofit leaders tend to rate themselves lower than those rating them do; they rate themselves lower on 12 of the 17 dimensions (see Table E). In contrast, for-profit leaders tend to rate themselves higher than the average ratings provided by feedback givers. They do so in 15 out of 17 dimensions (see Table F).

The relatively low self-ratings of nonprofit leaders on the ability to use temporary power, and to some extent lasting power, combined with the push-and-pull of multiple stakeholder expectations is a sure recipe for stress, which could explain nonprofit leaders’ lower ratings on the ability to cope with stress. Burnout has been a major factor for executive directors who leave their jobs.

Several questions come to mind. Are nonprofit leaders less aware of their strengths? Are they harder on themselves?

Based on our observations of nonprofit leaders and our consulting work in the nonprofit sector, we believe that nonprofit leaders are indeed harder on themselves concerning leadership and management than their for-profit counterparts. Having learned the leadership ropes on their own with little mentoring or formal leadership development, nonprofit leaders may not realize their strengths.

Are those rating nonprofit leaders more generous in their scoring? If so, why? The complexity of nonprofit leaders’ role, the reality of limited staff and funding resources, the intensity and breadth of day-to-day demands, and the relatively low compensation structure are known issues in the sector. With these factors as a point of reference, feedback givers—who see nonprofit leaders succeeding against all odds—may tend to rate them higher than feedback givers in the for-profit sector.

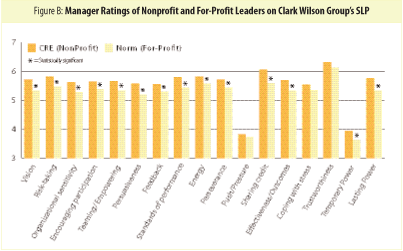

When we look more closely at managers’ ratings of the two sample groups, nonprofit leaders scored higher than for-profit leaders on all 17 dimensions (see Figure B). Moreover, the difference between their scores is statistically significant for 14 of the 17 dimensions. This invites questions not only about the significantly higher manager ratings of nonprofit leaders in 14 of 17 dimensions, but also, and perhaps more important, about the three out of 17 dimensions where the difference in the scores of nonprofit and for-profit leaders is not significant.

In viewing individuals in leadership positions (versus managerial positions), peer ratings bring the purest perspective because leadership is really about exercising influence. In the nonprofit world, the executive director-board relationship is closer to that of a peer relationship compared with the manager-direct report relationship in the for-profit world. Their relationship is not one of compliance. Board members follow an executive director’s lead not because they have to but because an executive director has effectively exercised influence skills. Therefore the manager ratings and peer ratings for nonprofit leaders give us the cleanest perspective.

Where manager ratings for nonprofit leaders are significantly higher, it may be the result of perceived resource inequity as experienced by nonprofit board members, many of whom come from the for-profit sector. These for-profit and business board members understand that for-profit leaders often have more abundant resources available to them. They recognize the amazing, even heroic, work nonprofit leaders do in the face of substantial resource constraints.

At the same time, manager ratings of nonprofit leaders highlight some challenges. According to manager ratings, nonprofit leaders demonstrate more effective leadership practices compared with for-profit leaders, except in three areas: push/pressure, the ability to cope with stress, and trustworthiness. The question here is why the managers of nonprofit leaders see these leaders as less effective in these dimensions compared with the other 14 dimensions. We are inclined to see the reasons for this through the dual lenses of accountability and power.

Both the literature on the nonprofit sector and our firsthand experience with nonprofit leadership attest to the relatively unclear lines of ownership and accountability. Unlike the for-profit sector where shareholder expectations tend to be more well defined and must be met or the organization risks financial instability, stakeholder expectations in the nonprofit sector may be misaligned, unclear, or shifting. Nonprofit leaders are tethered to many “masters,” all of whom have a stake in the organization but none of whom completely understands the organization. Meeting these various expectations may pose conflicts and diminish nonprofit leaders’ ability to push for results. This may also explain the low rating on trustworthiness, reflecting unfulfilled expectations.

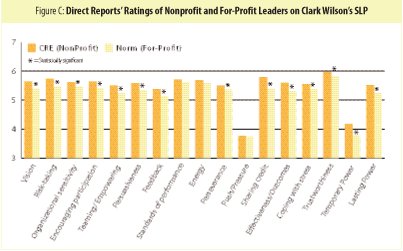

A closer look at direct reports’ ratings of leaders in the two sample groups highlights several similarities and a couple of differences between direct reports’ ratings and managers’ ratings (see Figure C).

Like managers’ ratings, direct reports’ ratings indicate that nonprofit leaders scored higher than for-profit leaders on all 17 dimensions and the difference between their scores is statistically significant for 14 of the 17 dimensions. They also agree that nonprofit leaders have difficulty exerting push pressure. But they differ as follows:

• In two dimensions—coping with stress and trustworthiness—the difference in manager ratings of nonprofit and for-profit leaders is not statistically signficant. But, in the ratings of direct reports of nonprofit and for-profit leaders on these dimensions, the difference is statistically significant. Evidently, direct reports of nonprofit leaders see them as able to cope with stress and as trustworthy.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

• In two other dimensions—standards of performance (i.e., holding people accountable) and energy level (i.e., a sense of urgency and desire to achieve results)—the reverse is true. The difference in manager ratings of the two sample groups is statistically significant, but the difference is not significant for direct reports. It appears that direct reports of nonprofit leaders see them as being challenged in these two dimensions.

Why the higher ratings of nonprofit leaders among direct reports? Several propositions are worth considering:

• Nonfinancial “lever.” Since compensation is not a “lever” in the nonprofit world, nonprofit leaders have to use other means, such as good leadership practices, to motivate people.

• Nonprofit culture. Nonprofits’ organizational culture is more accommodating of personal/family needs. It is not unusual to hear staff members in nonprofits cite this accommodation as a reason for working in the sector. And this accommodation is often tacitly or explicitly approved by nonprofit leadership.

• Role complexity. With limited resources, nonprofit leaders are put to the test in stepping up to the multidimensional aspects of their leadership role, from partnering with a board to connecting with funders to managing staff to reaching out to the community. More than anyone, direct reports know this firsthand.

Why do managers’ and direct reports’ ratings differ? In this study, direct reports are closer to the action than some managers and have a better sense of operations. They witness the myriad pressures that nonprofit leaders face and better appreciate what it takes to cope with those stressors. Their expectations may also be the most prominent for nonprofit leaders, and when those expectations are fulfilled, leaders may become more trustworthy in their eyes. By the same token, they are also more knowledgeable about how organizational and employee performance is managed and are more concerned about how a nonprofit leader sets standards to evaluate performance. Any “failings” of a nonprofit leader in this area affect direct reports significantly, and therefore this group is more sensitive to these concerns.

The findings also raise a question about why the difference in the ratings of nonprofit and for-profit leaders is not significant with regard to standards of performance and energy level. Compared with for-profit leaders, nonprofit leaders do not have the management tools and systems support to manage performance effectively. They typically don’t have access to the data that facilitates critical decision making. Unlike the outcomes expected of for-profit leaders—which tend to be visible, quantifiable, and measurable—the outcomes expected of nonprofit leaders require a logic model to articulate the desired change and the appropriate tools to measure that change.

The peer raters in the 360–degree feedback survey for nonprofit leaders tend to be different from those of for-profit leaders. Peer ratings for the latter group tend to come from within the organization, either from the same department or function as that of the for-profit leader or from other departments/functions in the organization. In the nonprofit scenario, executive directors often lack a peer within the organization. Respondents are typically executive directors of other organizations, colleagues outside the organization, and sometimes board members (but not board chairs). Deputy directors in small organizations may have no peers. And even in larger nonprofits, a deputy director may not have peers within the organization, so respondents typically include raters from outside the organization.

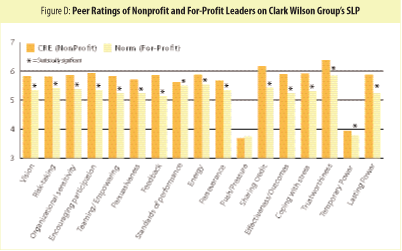

A closer look at the peer ratings of the two sample groups shows a striking result (see Figure D). The peer ratings for nonprofit leaders are all significantly higher than those of for-profit leaders. On the 17 leadership dimensions, peers see nonprofit leaders as demonstrating those leadership practices more frequently than for-profit leaders.

The overwhelmingly higher peer ratings of nonprofit leaders can be explained by several factors. In addition to the perceived resource inequity between the for-profit and nonprofit sector that explains managers’ ratings, there may be an empathy factor at work given that peers may be in similar positions as the individual being rated. They may recognize the hurdles that peers face and appreciate their successes.

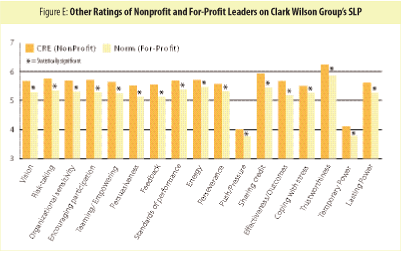

When we look more closely at ratings for the two sample groups by those in the “Other” category, one similarity runs across four categories of raters: self, manager, direct report, and other (Figure E).

They all agree that nonprofit leaders have not demonstrated effectiveness in the push/pressure leadership dimension. Responses from the Other category, however, indicate that nonprofit leaders score higher than for-profit leaders on 16 of the 17 dimensions, and the difference between their scores is statistically significant for 15 of the 17 dimensions. Other findings include the following:

• Unlike direct reports, those in the Other category say nonprofit leaders demonstrate energy toward achieving results.

• Unlike managers, those in the Other category saw nonprofit leaders as trustworthy and able to cope with stress.

• Like direct reports, those in the Other category say that nonprofit leaders are challenged by setting standards of performance.

For nonprofit leaders, the Other category of feedback givers is made up primarily of peers, the same observations discussed in the section on manager and peer ratings would hold. The results of this study are summarized in Table G.

While one should question whether the feedback givers of nonprofit leaders are more generous in their ratings, this hypothesis pales in the face of the remarkable role complexity that nonprofit leaders inhabit daily. This unrelenting role complexity combined with limited staff and funding resources, the intensity and breadth of day-to-day demands, and the relatively low compensation structure are well-known challenges of the sector. With these factors as a point of reference, feedback givers who see nonprofit leaders succeeding against all odds may tend to rate them higher than the feedback givers in the for-profit sector.

In order to develop more firm conclusions, further research is in order. For follow-up research, there are several questions of interest:

• Is this the right population for comparing nonprofit leaders? Is there any “right” population or are we simply comparing apples and oranges? If so, why?

• Since we now have nonprofit norms for the leadership practices survey, if we were to use those norms for additional nonprofit leaders, would they still outscore the for-profit leaders?

• Why do nonprofit and for-profit leaders score lower in certain leadership dimensions compared with other dimensions? Are the reasons the same?

• Are the high scores of nonprofit leaders correlated with organizational effectiveness and excellence? At this point, our findings simply show that nonprofit leaders demonstrate effective leadership practices. Whether those practices result in goal achievement is another question. A worthwhile follow-up study would examine whether the nonprofit leaders in the study have been able to translate those effective leadership practices into outcomes that make for organizational excellence.

If indeed there is a leadership deficit in the nonprofit sector, instead of looking outside the sector, it is incumbent on us to invest more deeply in leadership development. Our research and experience suggest the following:

• We have the leadership talent in the nonprofit sector, but it needs to be nurtured. Leadership development cannot be episodic. It must consist of sustained, ongoing, integrated efforts: combining leadership, managerial, and technical skills and pegged to career progression of nonprofit leaders.

• Leadership development efforts should leverage the strengths and assets of nonprofit leaders, which we have seen to be ample. These strengths and assets could be the bridge to addressing those areas where nonprofit leaders are challenged.

• We should work to increase the “conscious competence” of our leaders.

• Using this kind of data, we should help nonprofit board members understand the leadership strengths and challenges of their executive directors.

• We need to create more opportunities for nonprofit and for-profit leaders to come together to learn from one another. Most relationships between the two occur within a board setting.

• We need to develop organizational efforts that create a culture focused on accountability while sustaining a focus on people. Funders can support change efforts and the development of management tools to help leaders monitor accountability and to shore up leaders’ ability to use temporary power.

The view that for-profit leaders exercise more effective leadership skills than do nonprofit leaders is common not only in the for-profit world but in some segments of the nonprofit sector as well. In light of the recent buzz about a leadership deficit in the nonprofit sector, it seems easy to look to the for-profit sector for leadership talent. These findings indicate that the nonprofit sector may indeed have better leaders, and if it exists, the deficit is better addressed by exploring how we design and provide access to high-quality leadership development opportunities.

Leadership development must be an integral component of capacity-building efforts. But it is time to go beyond capacity building. With its considerable leadership talent, the nonprofit sector is poised to focus on excellence building and power projection. Our nonprofit leaders need support in transforming their organizations from being simply effective to being excellent. Nonprofit leaders have more power than they think. Using organizational structure as a lens, nonprofit leaders rely less on a pyramidal power structure. Instead, they lead from within a star-like structure, a constellation of stakeholders all around them instead of above or below them. This structure recognizes that power relationships are constantly shifting and that partnerships get results, especially when navigating change efforts. It is time to stop being the “weak sister” to the for-profit sector and to recognize and project the positive power and influence that nonprofit leaders have as they work in their communities, in the public forum of ideas and policy, and on behalf of the common good.