“In groups we can do together what we cannot achieve alone. With networks and new computer-based tools now ordinary people can become a group even without the benefit of a corporation or organization. They can make decisions, own and sell assets, accomplish tasks by exploiting the technology available. They no longer need to rely on a politician to make decisions. They can exercise meaningful power themselves about national, state and local—indeed global—issues. Senior citizens and teenagers use networked handheld computers to police the conditions of urban land use. The Google search engine offers a “Google Groups” service to make it easier for people to create and maintain groups and to do everything from “treating carpal tunnel syndrome [to] disputing a cell phone bill.” The mobile phone “smart mob” allows groups to self-organize a political protest or campaign, such as the one that elected the president of South Korea. Young people are meeting in video games and using the virtual world to organize real world charitable relief for victims of natural disasters. When the Chihuahua owners of San Diego, California, get together via Meetup.com, they discover not only a shared animal affinity, but also their ability to change the conditions of local parks, affect local leash laws, and police the park for themselves. Meetups have no offices, secretaries, water coolers, or other appurtenances of formal organizations yet they have as much effect. Parents come together to decide on policy in their children’s school or a group of scientists collaborate to overthrow an age-old publishing model and distribute their research collectively online.”

—Beth Simone Noveck, “A Democracy of Groups”1

“Wherever we look, we see a landscape of movement and complexity, of forms that come and go, of structures that are not from organizational charts or job descriptions, but from impulses arriving out of deep natural processes of growth and of self-renewal. In our desire to control our organizations, we have detached ourselves from the forces that create order in the universe. All these years we have confused control with order. So what if we reframed the search? What if we stop looking for control and begin the search for order, which we can see everywhere around us in living dynamic systems?

It is time, I believe, to become a community of inquirers, serious explorers seeking to discover the essence of order—order we will find even in the heart of chaos. It is time to relinquish the limits we have placed on our organizations, time to release our defenses and fear. Time to take up new lenses and explore beyond our known boundaries. It is time to become full participants in this universe of emergent order.”

—Margaret J. Wheatley, “Chaos and Complexity: What Can Science Teach?”2

“Wikis and other social media are engendering networked ways of behaving—ways of working wikily—that are characterized by principles of openness, transparency, decentralized decision making, and distributed action. These new approaches to connecting people and organizing work are now allowing us to do old things in new ways, and to try completely new things that weren’t possible before.”

—The David and Lucile Packard Foundation, “Network Effectiveness Theory of Change”3

If you want to have an effect on poverty, hunger, human trafficking, immigration, labor rights, the torture of political prisoners, the economic development of your region, education, healthcare, or any one of a number of issues we discuss and work on in this sector, it is likely you will be working in networks.

While networks have always existed in our work in the civil sector, we are all on a learning curve about their use. Our perception of them and our approach to working with them are changing with the facilitation of technology and the Internet. The potential of leveraged learning, reach, and impact through ever-expanding networks of networks calls us to engage—but if you take networks seriously, you will be working in a brave new world, with new dynamics and a lot more promise for change.

In this framing article, NPQ will try, in short form, to introduce you to some of the current thinking around the uses and benefits of networks, without hitting you with a lot of maps and discussions of qualifiers like “density.” To do so, we have compiled material from some of the thought leaders in this field. Please, though, read this with the understanding that we know you are already working in networks at many different levels; our goal with this article is to reveal some of the thinking around their strategic uses in achieving much bigger impact and influence than you have likely in the past enjoyed. (We do wish to acknowledge that we talk less here about networks of service or production than of those of social change. And, there are some fascinating models developing in the economy that we will address in our next edition of NPQ.)

|

Intentionality “Both organisations and individuals can participate in networks. But the participants in networks are characterized by their diversity, including geographical diversity, as well as cultural, lingual, and at times also ideological diversity.” “The way actors participate in networks is very diverse, ranging from voting in elections to participating in campaigns. Participation in networks is sporadic; at times very intensive, at times non-existent.” “A network may cease to exist once it reaches its goals, or the goals may be so broad and far-reaching that there is no reason for it ever to stop existing. Participation in a network will last as long as the members remain committed.”4 |

Curtis Ogden describes some of the values we have to hold in order to make good use of networks:

- Adaptability instead of control. Thinking in networks means leading with an interest in adaptability over time. Given contextual complexity, it is impossible for any actor or “leader” to know exactly what must be done to address a particular issue, much less keep what should be a more decentralized and self-organizing group moving in lockstep. Pushing “responseability” out to the edges is what helps networks survive and thrive.

- Emergence instead of predictability. As with any complex living system, when people come together as a group, we cannot always know what it is they will create. The whole is greater than the sum of the parts. Vying for the predictable means shortchanging ourselves of new possibilities, one of the great promises of networks.

- Resilience and redundancy instead of rock stardom. You see it on sports teams all the time. When the star player goes down, so goes the team. Resilient networks are built upon redundancy of function and a richness of interconnections, so that if one node goes away, the network can adjust and continue its work.

- Contributions before credentials. You’ve probably heard the story about the janitor who anonymously submitted his idea for a new shoe design during a company-wide contest, and won. “Expertise” and seniority can serve as a bottleneck and buzzkill in many organizations where ego gets in the way of excellence. If we are looking for new and better thinking, it should not matter from whence it comes. This is part of the value of crowdsourcing.

- Diversity and divergence. New thinking comes from the meeting of different fields, experience, and perspectives. Preaching to the choir gets us the same old (and tired) hymn. Furthermore, innovation is not a result of dictating or choosing from what is, but from expanding options and moving from convergent (and what often passes for strategic) thinking to design thinking.5

And the Barr Foundation recommends that you:

- Think about what you can do to increase your consciousness in using networks;

- Discover the hidden networks already in your operating environment and be more intentional about using them;

- Develop far-flung communities of practice—hives that create, adapt, and spread; and

- Be enthusiastic about the flowering of numerous experiments.6

What Networks Are

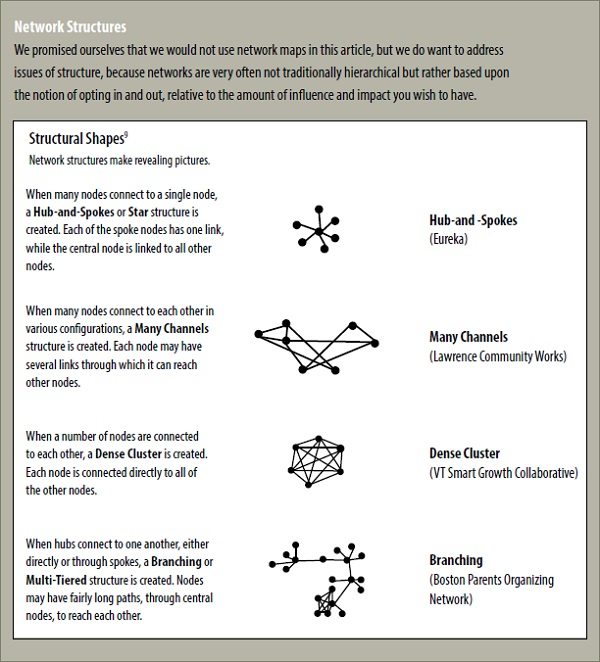

Very loosely described, networks consist of entities (nodes) in relationship with one another, and the flows (ties) that exist between them. These ties can be thought of as conduits or channels. The network is made up, then, not only of connected entities but of the stuff that is transferred between and among them, creating a “circulation of” and evolution of meaning.7 Networks often have hubs or cores that organize work. Sometimes there is one hub (even if it is made up of multiple members) and a more centralized approach to decision making, and sometimes there are multiple hubs, and the network essentially self-organizes, often through the sharing of information and strategy. In networks, the importance of loose ties is recognized. Network edges or peripheries consist of those who are involved, but less so.

These important actors in the network are the bridges to other networks that may, in fact, prove critically useful at some point to inform or lend weight to your network’s work.

Networks generally create value for individual members as well as for the network as a whole. They are reciprocal and tend to involve multiple value propositions for participants. They can be extraordinarily inclusive and rich in their diversity. In “A Network Analysis of Climate Change:Nonprofit Organizations in Metropolitan Boston,” Ben Steinberg writes that “the ability to learn new information becomes easier with access to nontraditional experts within the network who can synthesize technical content into understandable material.”8 Networks may be experienced as:

- Temporary or continuous;

- Spontaneous or planned;

- Requiring a heavy or light investment of us—and often both over time;

- More centralized or multi-nodal; and/or

- Relatively closed or open in terms of membership.

Networks are often built or cohere to take on complex problems over time. They are a form that offers a great deal of potential leverage and that can evolve and adapt quickly to changing times—passing a portion of that adaptability along to its members while being continuously informed by them.

Purposeful Action Networks

New forms of participation are emerging that are not dependent on identity, contiguity, or conversation. Peter Steiner’s famous New Yorker cartoon captioned “On the Internet, no one knows you are a dog,” might now be entitled “On the Internet, no one knows you are a pack of dogs.”

—Beth Simone Noveck,

“A Democracy of Groups”10

Sometimes, even the loosest of networks do not know they are headed toward an action until they get there, and they may not know that they are part of a larger network of concern. How does a diverse network of networks without centralized control pull it together to take cohesive action or make change? This can happen seemingly very quickly—in the blink of an eye—but there may be another understanding of that watershed moment.

Another form of the effect of networks as a totality on individual nodes is contained in the concept of “threshold,” or what is sometimes called the “tipping point.”11 This idea refers to the extent to which a given phenomenon is spread throughout a network. Once a certain level has been reached, all of the nodes join in the behavior or phenomenon. In this model, the probability of any individual node’s acting is a function of the number of other nodes in the network that have acted in a given way or possess the given quality. It is a step function, rather than a linear one. Thus, the action is not necessarily dependent upon one’s immediate partner(s) but rather on the relative number of nodes throughout the network that have adopted the given behavior or attribute. This is not only a key idea in “crowd behavior,” where the adoption of the behavior is visible to all, but also in other kinds of diffusion models. Following our insistence that network models apply to macro- as well as micro-phenomena, the adoption of behaviors by other organizations as an influence on the focal organization is a key component to the theory of the “new institutionalism.”

|

Characteristics of Action Networks

|

Social Change Networks

Networks do not have to progress to taking action together, but those that do have characteristics that are described well in “Organizations, Coalitions and Movements,” by Mario Diani and Ivano Bison. In the article, Diani and Bison describe the importance of the resilient diversity of networks to movement building or the pursuit of social change:

[T]he presence of dense informal interorganizational networks differentiates social movement processes from the innumerable instances in which collective action takes place and is coordinated mostly within the boundaries of specific organizations. A social movement process is in place to the extent that both individual and organized actors, while keeping their autonomy and independence, engage in sustained exchanges of resources in pursuit of common goals. The coordination of specific initiatives, the regulation of individual actors’ conduct, and the definition of strategies are all dependent on permanent negotiations between the individuals and the organizations involved in collective action. No single organized actor, no matter how powerful, can claim to represent a movement as a whole. An important consequence of the role of network dynamics is that more opportunities arise for highly committed or skilled individuals to play an independent role in the political process, than would be the case when action is concentrated within formal organizations.13

A paper by Ricardo Wilson-Grau and Martha Nuñez, on the uses of networks in taking on social change on an international scale, describes the distinct purpose that can be fulfilled by an international social action network:

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

[A] network offers unique political and organisational potential. Social change networks can influence economic, political and cultural structures and relations in ways that are impossible for individual actors. In these networks, the members are autonomous organisations—usually NGOs or community based organisations—and sometimes individuals. Furthermore, when the network is international, its aims and activities reflect the heterogeneous contexts represented by its members.14

An international social change network typically performs a combination of two or more of the following functions:

- Filtering, processing and managing knowledge for the members;

- Promoting dialogue, exchange, and learning among members;

- Shaping the agenda by amplifying little-known or little-understood ideas for the public;

- Convening organizations or people;

- Facilitating action by members and addressing global problems through knowledge of their local, national, and regional contexts;

- Building community by promoting and sustaining the values and standards of the group of individuals or organizations within it;

- Mobilizing and rationalizing the use of resources for members to carry out their activities; and/or

- Strengthening international consciousness, commitment, and solidarity.15

Benefits of Networks

While there is no choice about whether or not to engage in networks, one’s use of them can be more, or less, effective. There is no doubt that they require time and strategic thinking. So what are the paybacks if you are using the organization’s time to help networks develop?

In “Nonprofit Networking: The New Way to Grow,” Jane Wei-Skillern’s research-based opinions on the benefits of networks are described as including “mutual learning; enhanced legitimacy and status for the members; economic power; and an enhanced ability to manage uncertainty.” And, she suggests that nonprofits may be more suited to the network form, because the issues they are trying to solve are “large, complex problems that can’t be addressed by any single entity. Furthermore, nonprofits seek to create social value, not just organizational value; have dispersed governance structures . . . and rely heavily on trust and relationships to accomplish their work.”16

Additionally, Wei-Skillern believes that working within networks might help them to focus on their cause in a more entrepreneurial way than if they were working as a growing individual organization. Such growth, she believes, focuses leaders on management challenges at the organizational level, when they should be thinking more about “how best to mobilize resources both within and outside organizational boundaries to achieve their social aims.”17

Networks allow us to achieve some of the benefits of scale with few of the downsides, and to craft more comprehensive approaches to social problems than we can manage as single organizations. They provide the ability to link local approaches to national and international efforts, or to create “value chains” across dissimilar organizations that complement one another’s work.

In their handbook Net Gains, Madeleine Taylor and Peter Plastrik describe network effects that distinguish networks from organizations:

- Rapid growth and diffusion. A network grows rapidly as new members provide access to additional connections, thus enabling the network to diffuse information, ideas, and other resources more and more widely through its links.

- “Small-world” reach. A network creates remarkably short “pathways” between individuals separated by geographic or social distance, bringing people together efficiently and in unexpected combinations.

- Resilience. A network withstands stresses, such as the dissolution of one or more links, because its nodes quickly reorganize around disruptions or bottlenecks without a significant decline in functionality.

- Adaptive capacity. A network assembles capacities and disassembles them with relative ease, responding nimbly to new opportunities and challenges.18

|

Thought-Provoking Hypothesis from the Packard Foundation ”Healthy networks measure their impact, in particular by establishing the links between decentralized network action and outcomes.”19 |

Observing with Many Eyes—Understanding What the “It” Is that the Network Addresses

Jay Rosen, a media observer, wrote a column a few years ago titled “Covering Wicked Problems,” in which he describes how journalists might better cover problems like climate change:

Suppose we had such a beat. How would you do it? How might it work? . . . It would be a network, not a person. My friend Dan Gillmor, the first newspaper journalist to have a blog, said something extremely important in 1999, when he was reporting on Silicon Valley for the San Jose Mercury News. “My readers know more than I do.” So simple and profound. Any beat where the important knowledge is widely distributed should be imagined from the beginning as a network.

The wicked problems beat would have to be a network because the people who know about coping with such problems are unevenly distributed around the world. Imagine a beat that lives on the Net and is managed by an individual journalist but “owned” by the thousands who contribute to it. Journalists from news organizations all over the world can tap into it and develop stories out of it, but the beat itself resides in the network. In the way I imagine this working, news organizations that are members of the beat might “refer” problems discovered on other beats to the wicked problems network and say . . . “look into this, will you?” The beat would in turn refer story ideas and investigations back to the member newsrooms . . .20

This method of understanding a thing has many benefits, in that it allows the “it” to be viewed and defined from multiple perspectives in different contexts, and on a continuous basis as the “it” changes in response to environmental and developmental factors. This makes it well suited to the times and to the diversity of our sector. It is also an old saw of organizing that people take ownership of things that they help to define, so that there is a link between definition and action.

Mobilizing through Networks

The creation of a social response to a national or even global concern can “self-organize” very quickly now with the revelation of a problem hitting an existing interest network. The multiplier effect of networks informing networks happens quickly, and in many cases actions begin to take form at the nodal level. One node might take on a legislative push while another node organizes a boycott of some sort. The actions are loosely connected but coordinated by a purpose and the knowledge of what is occurring elsewhere.

This multi-nodal model is different from an industrial view of networks, which has often envisioned them as having a single hub with multiple spokes. Valdis Krebs and June Holley, in their paper “Building Smart Communities through Network Weaving,” suggested that this sort of network was “only a temporary step in community growth. It should not be used for long because it concentrates both power and vulnerability in one node.”21 The beauty of a multi-nodal network is that it leaves the network less vulnerable to single source failure and it also expands the “edges” of the network. Those edges are important, because the people there likely belong to and can bridge to other networks. As a network grows, there will be some nodes with close ties, which help to organize activity of the whole; but the growth will include a lot of looser ties, which facilitate the flow of information from otherwise distant parts of a network. Charles Kadushin writes that “social systems lacking in weak ties will be fragmented and incoherent. New ideas will spread slowly, scientific endeavors will be handicapped, and subgroups that are separated by race, ethnicity, geography or other characteristics will have difficulty reaching a modus vivendi.”22 But, again, the whole network functions on reciprocality. So, according to Kadushin:

Cores possess whatever attributes are most valued by the network. While this seems like a simple tautology it is not and may be the result of extremely complex processes. The network is about relationships and flows, not about the attributes of the nodes. This proposition says that in core/periphery structures the valuation of the attributes is related to the structure. The proposition does not state which comes first, however one must ask, do the nodes that have the most of what is valued come to be the core, or do the nodes that already have the most of what is valued impose their values on others who have less and confine them to the periphery?23

The creation of a network of longer-term action often requires more intimacy, because you must depend upon one another in a sustained strategy, but both types of networks exist in a world where boundaries are shifting and becoming more permeable. Some of this may be due to the fact that greater numbers of people are participating in greater numbers of networks; and to some extent within that context, focus and loyalty to a particular common cause may become the boundary that matters.

Making things more interesting, hybridity exists within networks quite naturally. Individuals and organizations may contribute in small or large ways; nonprofits and for-profits, co-ops and parties and government agencies, may participate in getting something done in common with one other, ensuring that their organizational purpose is met within the larger effort. But all is not equal in network land—some have the resources to get a bird’s-eye view of emergent patterns through the surveillance of others. This occurs not only in the government sector but also in business, and, probably to some extent, among independent hackers. But the large majority of us must depend upon the sometimes chaotic world of creating common cause and new order through shared experience, strength, and hope. In “Chaos and Complexity: What Can Science Teach?,” Margaret J. Wheatley stated:

At the end of the 1970s, Ilya Prigogene won the Nobel Prize for exploring what happens to living organic systems when confronted with high levels of stress and turbulence. He found that they reached a point in which they let go of their present structure. They fell apart, they disintegrated. But they had two choices. They could die or reorganize themselves in a self-organizing process and truly transform their ability, their capacity to function well in their changing environment.

This self-organizing process feeds on information that is new, disturbing and different. We are confronted with information we cannot fit into the present structure, and our first response to that kind of information (whether we are molecules or CEOs) is to discount it. We push it away. But [if] the information becomes so large and meaningful that the system cannot hold it, then the system will fall apart. But it will fall apart with the opportunity to reconfigure itself around this new information in a way that is more adaptive and healthier. It can suddenly explode, grow and change.

Erich Jantsch, a systems scientist, said that “self-organization lets us feel a quality of the world which gives birth to ever new forms against a background of constant change.”24

• • •

Later in this issue, thanks to the Management Assistance Group (MAG), you will see a few leadership case studies that discuss what is necessary at a personal level to be one of many leaders in a network, especially when heading an organization. You will also read about how organizations change when they become part of a networked effort. This may mean that our organizing principles are changing a bit, or at least that the contradiction between consolidation under the few and order of the many is playing out full blast among us. At the core of that is the struggle for and against control as the arbiter of order.

Notes

- Beth Simone Noveck, “A Democracy of Groups,” First Monday 10, no. 11 (November 7, 2005), firstmonday.org/article/view/1289/1209.

- Margaret J. Wheatley, “Chaos and Complexity: What Can Science Teach?,” OD Practitioner 25, no. 3 (Fall 1993), 3, www.margaretwheatley.com/articles /Wheatley-Chaos-and-Complexity.pdf.

- The David and Lucile Packard Foundation, “Network Effectiveness Theory of Change,” 2009, 2, www.packard.orghttps://nonprofitquarterly.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/07/OEnetwork- theory-of-change-2010.doc.

- Ricardo Wilson-Grau and Martha Nuñez, “Evaluating International Social Change Networks: A Conceptual Framework for a Participatory Approach,” Development in Practice 17, no. 2 (April 2007): 260.

- Curtis Ogden, “Network Thinking,” IISC Blog, December 14, 2011, interactioninstitute.org/blog/2011/12/14/network-thinking/.

- Peter Plastrik and Madeleine Taylor, Network Power for Philanthropy and Nonprofits (Boston: Barr Foundation, 2010), adapted from “Strategies for Network Approaches,” 25, www.barrfoundation.org/files/ Netork_Power_for_Philanthropy_and_Nonprofits.pdf.

- Ben Steinberg, “A Network Analysis of Climate Change: Nonprofit Organizations in Metropolitan Boston,” graduate thesis, Tufts University, August 2009, https://ase.tufts.edu/polsci/faculty/portney/steinbergThesisFinal.pdf.

- Ibid., 30.

- Plastrik and Taylor, Network Power for Philanthropy and Nonprofits, 19.

- Noveck, “A Democracy of Groups.”

- See Mark Granovetter and Roland Soong, “Threshold Models of Diffusion and Collective Behavior,” Journal of Mathematical Sociology 9, no. 3 (1983): 165–79; Thomas W. Valente, Network Models of the Diffusion of Innovations (Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press, 1995); Thomas W. Valente, “Social Network Thresholds in the Diffusion of Innovations,” Social Networks 18, no. 1(1996): 69–89; and Malcolm Gladwell, The Tipping Point: How Little Things Can Make a Big Difference (New York: Little Brown & Company, 2000).

- Claire Reinelt, “Visualizing the Landscape of Action Networks: An Application of Social Network Analysis,” Leadership Learning Community, blog, March 29, 2012, https://leadershiplearning.org/blog/claire-reinelt/2012-03-29/visualizing-landscape-action -networks-application-social-network-anal.

- Mario Diani and Ivano Bison, “Organizations, Coalitions and Movements,” Theory and Society 33 (2004): 283, eprints.biblio.unitn.it/1146/1/Diani_T&S_2004. pdf.

- Wilson-Grau and Nuñez, “Evaluating International Social Change Networks,” 258.

- Ibid., 258–59.

- Martha Lagace, “Nonprofit Networking: The New Way to Grow,” Harvard Business School Working Knowledge, May 16, 2005, hbswk.hbs.edu/item/4801. html.

- Ibid.

- Plastrik and Taylor, Net Gains: A Handbook for Network Builders Seeking Social Change, Version 1.0 (2006), 18, www.arborcp.com/articles/NetGains HandbookVersion1.pdf.

- The David and Lucile Packard Foundation, “Network Effectiveness Theory of Change,” 10.

- Jay Rosen, “Covering Wicked Problems,” Jay Rosen’s Press Think, June 25, 2012, pressthink.org/2012/06/covering-wicked-problems/.

- Valdis Krebs and June Holley, “Building Smart Communities through Network Weaving” (2002–6), 8, www.orgnet.com/BuildingNetworks.pdf.

- Charles Kadushin, Understanding Social Networks: Theories, Concepts, and Findings (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012), 31.

- Ibid., 54.

- Wheatley, “Chaos and Complexity: What Can Science Teach?,” 5.