February 17, 2015; Bloomberg

When the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation moves around pieces of its investment portfolio, people stand up and take notice. News just came out that in the last quarter of 2014, the Gates Foundation Asset Trust liquidated its positions in three important companies by selling millions of dollars worth of stock:

- 10.9 million shares of McDonald’s, valued at $1 billion

- 21.4 million shares, valued at $914.2 million, in Coca-Cola

- 8.1 million shares in Exxon Mobil, valued at $765.9 million

Over the years, the Gates investment managers have been reluctant to talk about their investment choices and hesitant about making fast moves. For example, they responded only slowly to pressures to divest from investments in the Sudan, though in the end, with the context of Sudan’s violent activities in Darfur and South Sudan, Gates ultimately did divest. Without crediting external influences for the move, Gates also divested last year from a British company providing security equipment and prisons for use by Israeli military occupying the West Bank. However, last year, an article in The Nation indicated that Gates still held $1.2 billion in stock investments in companies involved in alcoholic beverages and in military weaponry; further, it has holdings in such oil and gas companies as BP and Royal Dutch Shell in addition to ExxonMobil.

Truth be told, with more than $40 billion in investments, Gates has a toehold—or more—in some sometimes-less-than-savory corporate entities. In its 2012 Form 990, the Gates’ investment holdings provide plenty of grist for divestment activists of all sorts. Some of the corporate holdings in that document included positions in oil corporations such as Chevron, Marathon Oil, Petrobras, Royal Dutch Shell, Statoil, Hess, and others. In addition, there is a striking level of Gates investment in Wal-Mart, totaling well over $1 billion. There’s something for everyone in the Gates holdings.

While Gates doesn’t specifically explain the reasons behind the divestment from Mickey D’s, Exxon, and Coke, they are interesting choices with possible symbolic and substantive meaning for the philanthropy. For a foundation like Gates that has made health one of its priorities, for example, McDonald’s is sort of the antithesis. Although still massive, MCD didn’t have a good year on the stock market last year, with shares down three percent while the NYSE overall rose 18 percent. Some might attribute that to competition from Burger King and Wendy’s, but others might say that, slowly but surely, the public is wising up to the clogged-arteries diet of McDonald’s and considering healthier options.

McDonald’s may also be as unhealthy to the wages of working people as it is to their heart conditions. Last month, McDonald’s decided to omit from its proxy statement a shareholder proposal that would simply encourage, not even require, McDonald’s franchises to pay its workers a minimum of $11 an hour. The resolution suggested that the company could compensate franchises that pay the higher wage by reducing the service fees franchises pay to the corporate parent or by raising the prices of food sold at McDonald’s. The company was obviously not thrilled with the notion of shareholders addressing labor conditions and booted the proxy on the grounds that shareholders need not weigh in on business operations like wages.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

A resolution filed by Harrington Investments called on MCD to report to shareholders on the congruence between corporate values and the company’s political contributions and trade association fees. The Harrington resolution suggested that McDonald’s support of politicians and organizations opposing minimum wage increases contradicts the company’s stated pledge to treat employees with “fairness, respect and dignity” and that the company’s commitment to food safety and quality was contradicted by its support of politicians who oppose GMO labeling and its partnerships with companies such as Monsanto that use GMO products. While McDonald’s shareholders have not been open to some important shareholder resolutions in the past, these shareholder actions raise important questions about the company’s societal role and impact.

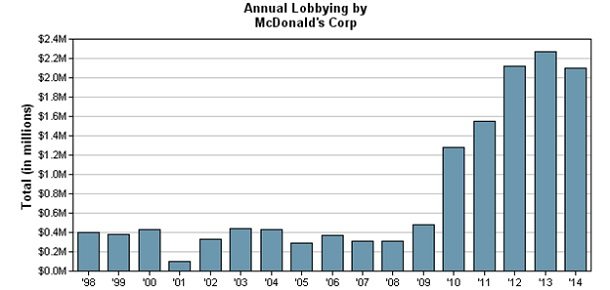

Although McDonald’s has been declining on the stock market, its investment in lobbying has increased dramatically in recent years, particularly as it has had to face off against the demands of fast food workers who are increasingly protesting their miserable wages. The following chart from the Center for Responsive Politics shows the huge growth of MCD’s lobbying:

Regarding its investments in oil and gas companies, Gates could have divested totally from its carbon-connected portfolio, but it doesn’t seem to have done so. However, ditching ExxonMobil is a high profile step, as ExxonMobil has been an industry leader in climate change denial, fighting off carbon emission regulation with a gusto abetted by a major political campaign and lobbying apparatus. For example, in federal lobbying, ExxonMobil is usually at the top (or close to it) of the oil and gas industry in terms of lobbying expenditures, according to data on the website of the Center for Responsive Politics:

- 2014: #2, with lobbying expenditures of $12.65m (Koch Industries was #1)

- 2013: #1, with expenditures of $13.43m (Chevron was #2 at $10.53)

- 2012: #2 spending $12.97m (Royal Dutch Shell was #1 with $14.48m and Koch was #3 at $10.55m)

- 2011: #3, spending $12.73m (behind #1 ConocoPhillips $20.557m and #2 Royal Dutch Shell $14.79m)

Pending shareholder resolutions addressing ExxonMobil include one filed by As You Sow and Arjuna Capital/Baldwin Brothers asking that the company return cash to shareholders rather than investing in new oil fields (the “Carbon Bubble 2015” resolution) and another requiring the company to report fully to shareholders on minimizing the adverse environmental impact of hydraulic fracturing operations.

A Gates divestment decision in 2014 sends a signal to the activist and philanthropic communities. Other foundations may watch Gates and realize that shedding noxious investments that contradict foundation values is important and necessary. Activists might follow up on the divestments from ExxonMobil and McDonald’s with more scrutiny of Gates investments in companies like Wal-Mart that may not be particularly labor-friendly, banks that have been in the forefront of bringing the housing market to its knees through lousy mortgages and rampant foreclosures, and pharmaceutical companies whose policies sometimes make the Gates Foundation’s own health priorities difficult to realize. Even better would be examining the investment decisions of all major foundations and calling them on the carpet for investments that appear to contradict their philanthropic grantmaking missions and priorities.—Rick Cohen