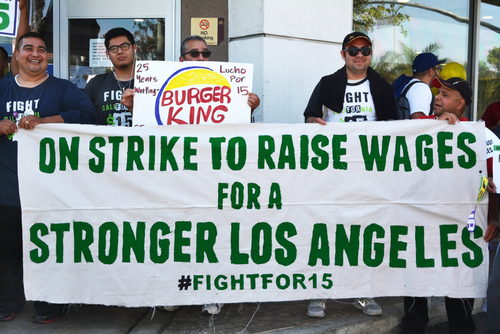

Dan Holm / Shutterstock.com

June 4, 2015; Daily Bruin

Although the federal minimum wage in the U.S. is only a measly $7.25 an hour, states and cities can go higher. Twenty-nine states and a number of large cities, including Seattle, San Francisco, Chicago, and Washington, D.C. have established higher minimum wage levels. The latest is Los Angeles, but a number of nonprofits—and, surprisingly, labor unions—have asked for exemptions.

The higher minimum wage starts in July 2016, moving to $10.50 an hour, with annual increases up to $15 an hour by 2020, but is delayed for nonprofits by a year. That $10.50 wage equates to a gross annual income of $21,840, barely above the federal poverty level for a family of three. A number of Los Angeles area nonprofits that train workers to re-enter the workforce and in doing so provide counseling and educational services argue that the higher minimum wage, especially the eventual $15/hour, will force them to cut back their programs and lay off trainees. The nonprofits include Homeboy, which provides transitional job training for former gang members, and Chrysalis, which helps the homeless.

Politically conservative opponents of higher minimum wages often use nonprofits as a “front man,” according to California Association of Nonprofits executive director Jan Masaoka, but most nonprofits, including most CAN members, support the minimum wage hike. However, CAN advocated for the longer lead-in time for nonprofits so that they might renegotiate government contracts on their labor reimbursement rates.

Still, a number of nonprofits have expressed reservations on the minimum wage. Of 34 members responding to a survey from the Nonprofit Association of Oregon taking a position on a $15/hour minimum wage, 11 said they were opposed. Of over 130 survey respondents, regardless of their position on the minimum wage, only 10 said they would absorb the wage increase with little problem. As a result, in Portland, Oregon, says Stephen Beaudoin, the director of a nonprofit serving persons with disabilities, nonprofit employers have not been visible advocates for nonprofit wage parity in that city’s exploration of a $15/hour minimum age. Seattle’s Human Services Coalition took a middle-of-the-road position on that city’s proposed wage hike, calling for it to be done “in a thoughtful manner to prevent unintended consequences.” Overall, nonprofits are conceptually in favor of a higher minimum wage as a step toward reducing social inequities, but sometimes tepid in their public support because of concerns for their own payrolls.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

While some nonprofits might be lukewarm about a higher minimum wage, the signal from organized labor in Los Angeles is downright contradictory. Organized labor vigorously supported the $15/hour minimum wage, but then the Los Angeles County Federation of Labor, the local affiliate of the AFL-CIO, argued that workplaces covered by collective bargaining agreements should be allowed to opt out. Labor’s support for what they call a “collective bargaining supersession clause” means that union workplaces would be exempt from the higher minimum wage, but nonprofit employers, almost always not unionized (except for hospitals and universities), would not have that option.

It raises some serious issues for the minimum wage increase. Would employers be incentivized to accept unions on the theory that they could negotiate wages below the minimum wage? What is the signal that unions are sending to Los Angeles workers? Writing for the Daily Bruin, Travis Fife makes the challenge clear: “The union’s backtracking has given many people mixed signals, and that’s disappointing because the minimum wage increase sent a clear message—Los Angeles workers deserve more. Now unions must choose to be consistent with that.”

Else, the message is that despite the increase of the minimum wage, the unions are implicitly acknowledging that some industries might not be able to support a $15/hour minimum wage. Slate’s business and economics reporter, Jordan Weissman, gives examples:

“To be clear, this is almost surely an implicit acknowledgment by the unions that there are at least some local industries in Los Angeles, such as apparel manufacturing, where $15 per hour is too high a minimum, and workers might prefer to accept lower pay in order to keep their jobs…It’d potentially be fascinating to watch a scenario play out where some fast-food restaurants, for instance, let in unions to save on their payroll, while others try to make the math work at $15. Maybe we’d discover that organized labor wouldn’t be so poisonous for the financial health of a McDonald’s after all.”

Think of it for nonprofits. Is the Labor Council suggesting that nonprofits would get an exemption if they were to accede to union representation for their employees? And if they don’t, would they be held to the new, higher minimum wage? Los Angeles isn’t the first city raising its minimum wage with a union exemption: San Francisco, Oakland, and Chicago have done so as well, though Seattle has not. What has been the impact of these cities’ new higher minimum wages on nonprofits—especially with the impact of the union exemption? Nonprofit Quarterly wants to hear from you.—Rick Cohen