Editors’ note: This article was the last that Rick Cohen wrote for the Nonprofit Quarterly, and it was one of his most ambitious in its weaving of political, philanthropic, and community intentions, partnerships, and realities. Rick died suddenly just as we were beginning our edit, and we were left with the sad task of doing the best we could without his input—any errors of fact should be put down to the editors, and life’s interruptions of this process. That said, this case study of an historic interplay between the sectors to try to save a city, and the intended and unintended consequences that resulted, is sure to become a classic. It can be found in the Nonprofit Quarterly’s winter 2015 edition, “When the Show Must Go On: Nonprofits & Adversity.” There will be a memorial held for Rick Cohen on January 12, 2016.

Donna Murray-Brown, CEO of the Michigan Nonprofit Association, lives the duality experienced by many Detroiters faced with tough decisions to make for the city’s economic recovery. On the one hand, she is a nonprofit executive, a public policy advocate, and—to some extent—a player at the table in the discussions of what Detroit needs to do to recover from the brink of economic collapse and chart a path toward citywide recovery; on the other hand, she is the daughter of a senior Detroiter whose retirement pension was reduced as one of the components of the partly foundation-funded “grand bargain” that became the blueprint for Detroit’s escape from a prolonged and debilitating bankruptcy. Her father’s perception is that the grand bargain and other elements of Detroit’s rescue involve things “being done to him rather than for him.”1

In a way, that is the real challenge of Detroit’s recovery: the contrast between bold, innovative ideas that envision a very different Detroit from the prosperous manufacturing metropolis of half a century ago, and the conditions of longtime residents of the Motor City—a population that is in high majority black, mostly lower income, in many cases unemployed or underemployed, and at risk in the tens of thousands of displacement due to tax foreclosures, mortgage foreclosures, unpaid water bills, and—surprisingly for a city that has huge tracts of vacant, dilapidated buildings—pockets of upscale gentrification. How does Detroit come back from the verge of economic collapse and municipal bankruptcy to devise and implement a future for long-established Detroiters and new residents?

A History of Unrealized Plans and Hopes

In the wake of Detroit’s declaration of municipal bankruptcy and complex plan involving state, municipal, and philanthropic resources to escape that bankruptcy, the city still looks and feels to many Detroit residents like it is staggering along a difficult trajectory toward its goal of sustainable revitalization.

Detroit is the poorest large city in the United States. It has significant unemployment—officially, nearly 13 percent in August 2015, and an unofficial rate that may well be double or triple that, if we take into account people having given up looking for jobs or whose unemployment benefits have expired. It also has significant underemployment, due to the automotive industry’s having shrunk and largely decamped—leaving vast tracts of vacant land and buildings across the 139-square-mile Detroit footprint as an additional result.2 Plans to bring Detroit back from the edge of collapse and despair aren’t new to Detroiters; as the city has slid in population and economic significance over the past few decades, reams of renewal initiatives emerged from public-sector, private-sector, and philanthropic sources, with the aim of jump-starting the community’s flagging socioeconomic dynamic and reversing what seemed to many an inexorable decline.

One such initiative, the waterfront Renaissance Center, aimed to capture residents and business headquarters that were leaving for the suburbs or beyond. During the administration of Mayor Coleman A. Young (1974–94), the Renaissance Center was completed—along with other major projects, including the Detroit People Mover, an elevated train meant to transport people through the Downtown area, and the redevelopment of the Joe Louis Arena, home of the Detroit Red Wings National Hockey League team. (The arena is already outmoded and about to be replaced.) Mayor Dennis W. Archer (1994–2002) launched a variety of community-oriented initiatives (though his major economic achievement for the city may have been his success in making casinos a linchpin of Detroit’s Downtown activity) and, like his predecessor, promoted major sports stadium projects, realized after his term in office (Ford Field, where the National Football League Detroit Lions play, and Comerica Park, home to Major League Baseball’s Detroit Tigers).

Nonetheless, Detroit’s slide continued largely unabated, despite the new sports venues and casinos. And, with the support of business, philanthropy, and the federal government, Detroit hosted other initiatives aimed at neighborhood and citywide renewal. In the early 1990s, Detroit was one of six “urban empowerment zones” meant to benefit from a $100 million federal grant infusion plus a variety of federal tax incentives, which the city devoted in significant amount to human services needs and issues—notably, community policing and the integration of criminal justice programs and functions.3 Several years after the “urban empowerment zone” designation, an analysis called Detroit’s use of the program “spectacularly unsuccessful” and—notwithstanding a few entities that took advantage of tax incentives and some of the grant funding—having made, in the words of a Detroit Free Press article, “zero difference to most Detroiters.”4 This was followed by former mayor Dennis Archer’s Community Reinvestment Strategy, a neighborhood planning process focused on ten cluster areas. Although involving extensive citizen participation through meetings and focus groups, the results were seen as “overly ambitious wish lists of every community in the city,” “not grounded in fiscal reality,” and “presented in a ‘planning vacuum’ with no overall policy framework for physical development outside the downtown area.”5

Over the years, the themes undermining Detroit’s efforts to change course have been consistent: weak political leadership; an inability to establish priorities in a large city with multiple neighborhoods in physical and economic tatters; and success in helping some Downtown interests and major redevelopment projects, but with little corollary benefit to neighborhoods and the longtime Detroiters who live there.

Why should Detroiters think the city’s current post-bankruptcy status will reverse the long slide toward economic obligation? The challenge is not whether or not the grand bargain proves to be a successful lever that vaults the city government past bankruptcy but rather whether or not the actions of state and local government, nonprofits, and foundations move Detroit into a trajectory of sustainable recovery.

Reflections on a Grand Bargain: Challenges of Democracy

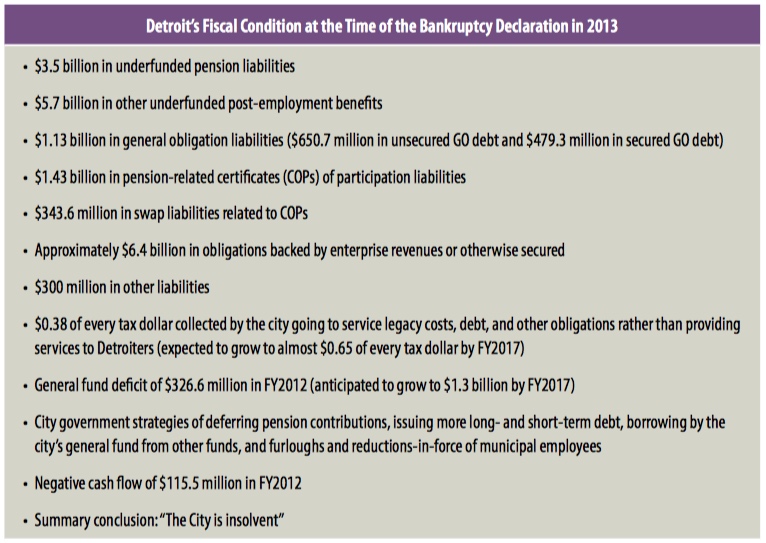

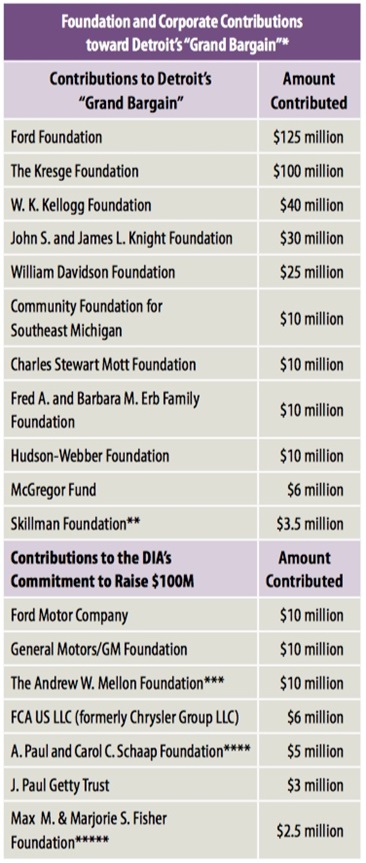

Detroit’s new path was crafted as much in federal bankruptcy court as in the offices of local government, and overseen by an emergency financial manager appointed by the governor—amid revitalization plans that emerged from foundation-sponsored collaborations and public-private partnerships. This path may have stemmed from the 2014 deal between private foundations, the state government, and the Detroit Institute of Arts (DIA) that became known as the “grand bargain”; but the true bargain wasn’t the one struck by the three dealmakers. Among all the potential creditors that the bankrupt municipal government had to fend off, the most important in a moral and perhaps legal sense were the retirees who had worked for the police department, the fire department, and other city agencies, paying into pensions they thought were going to support them when they retired. With an infusion of approximately $366 million from foundations into the bankruptcy settlement (through the artifice of saving the collection of the municipally owned Detroit Institute of Arts from public auction), what resulted was a “haircut” for retirees—a minor reduction of 4.5 percent in the pensions of most general government retirees, the elimination of cost-of-living increases, and a cutback in postretirement health benefits.6 Facing the prospect of no resolution to the bankruptcy and unforeseeable litigation to exact money out of a bankrupt city, two-thirds of retirees voted in favor of the deal—essentially waiving their constitutional rights, as Michigan Attorney General Bill Schuette acknowledged.7 Through this mechanism, retirees lost much less than other creditors—but, in the words of Fortune magazine, “the average pensions in Detroit are so modest that any cuts will surely be painful.”8 (The modern-day equivalent to President Reagan’s mythical “welfare queens” is today’s no-less-mythical “retired cops with $100,000 pensions.”9 Like the welfare queen driving a Cadillac, perhaps there exists the occasional retiree basking in a six-figure annual pension; but in Detroit, general retirees receive average annual pensions of $19,000—those who receive social security—and police and fire retirees receive annual pensions of $32,000—those who do not.10)

The grand bargain has been heralded inside and outside of philanthropy as the linchpin of Detroit’s ability to move beyond the stalemate of a prolonged bankruptcy—an unprecedented philanthropic collaboration, albeit crafted by the federal bankruptcy judge, Gerald Rosen, who sketched the mechanisms for inserting foundation money into the deal in a doodle on the back of a legal pad: a sketch with arrows linking the words “art,” “pensions,” “state,” “foundations,” “private sources,” “timeline,” and “how much.”11 But there has been a concurrent background debate within philanthropy about the wisdom of foundations pledging nearly $400 million dollars to bail the Detroit city government—and, implicitly, the state government, as well—out of obligations taken on by the government. None of the previous or contemporaneous municipal bankruptcies encountered elsewhere in the nation (such as Central Falls, Rhode Island; San Bernardino, California; Stockton, California; Jefferson County, Alabama; and Harrisburg, Pennsylvania) had led to anything like the grand bargain—though, to be fair, none was anywhere near the magnitude of Detroit’s Chapter 9 filing.

Critics (who declined to be quoted on the record—partly because of a concern about harming their institutions’ relationships with the major foundations that had committed to the grand bargain) focused significantly on the process of how the deal came together, and cited the backroom dynamic of the negotiations—noting that, as one put it, there was a “lack of democracy in the whole process” and not much evidence of the city’s own elected officials being substantive participants in the game. One critic acknowledged, however, that while the grand bargain may have been less than democratic, his own family (which included retired Detroit city employees) was already suffering from a dysfunctional city government that had caused the city to deteriorate into incapacity over the years (with the corrupt 2002–08 administration of Kwame M. Kilpatrick being the final nail in the coffin), and feeling largely disenfranchised.

Rather than looking at Detroit as a sui generis implosion, some observers noted that Detroit had been allowed to languish—or was perhaps pushed toward an inexorable decline—by actions of the southeast Michigan region, whose residents worked in Detroit but went home to wealthy suburbs at the end of the day, and by the decisions of the state government, which had starved Detroit of needed state government resources. Surprisingly, perhaps as a reflection of how government and society have changed over the decades, there was little or no blaming of the federal government under the Obama administration, whose posture toward Detroit was not much different from President Gerald Ford’s apocryphal “drop dead” denial of federal assistance to New York City in 1975.12

Nevertheless, critics within philanthropy also acknowledged the fear that Detroit would become the philanthropic equivalent of Flint, Michigan. Long the focus of the Charles Stewart Mott Foundation, Flint’s problems have been endemic, including unemployment, poverty, and large-scale breakdown of municipal services. (Ironically, with respect to the latter, the problem of a contaminated municipal water system led Flint recently to connect to the decrepit and controversial Detroit water system.13) Detroit hadn’t been working for years—streetlights off, police and fire responses slow to nonexistent, garbage pickup intermittent, public facilities visibly and rapidly deteriorating. Even for critics and for foundations that came late to the deal, the grand bargain is recognized as a necessary if synoptic action. Church leaders in Detroit neighborhoods, one source said, told their parishioners that the grand bargain might or might not have been a “good deal,” but it was necessary to break the city’s governance coma and financial slide.14

In 2013, in a presentation at the Bradley Center for Philanthropy & Civic Renewal at the Hudson Institute, Tonya Allen, the president and CEO of the Skillman Foundation, declared that “philanthropy has had to step up to fill this void of city leadership and a void of leadership by the civic class.”15 At that time, perhaps as the grand bargain was first taking shape, Allen advised her fellow philanthropists that “we should not allow ourselves to have undue influence on processes that need to be and ought to be democratically controlled…. [In Detroit] we have stepped in entirely too much. We have not only funded it for the public good, then we’ve advocated where we want it to go and then we also advocate that those decisions go to institutions that we primarily fund. I think that is a fundamental flaw.”16

Two years later, the Skillman Foundation became one of the funders engaged in the grand bargain. Allen explained that unlike the trajectory of disappointment and failure that had been the norm in Detroit up to the bankruptcy, the grand bargain, regardless of its having been conjured outside of democratic processes, “gave everyone a collective memory of doing something hard and difficult and being successful.” At the point of the bankruptcy, Detroit had become a “broken municipality,” meaning that its governing apparatus was incapable of functioning for just about anyone. For all the efforts of foundations and nonprofits up to that point, without having a chance for the municipality to function those efforts would be for naught. “If you don’t have a working municipality, then none of the investments you make will be sustainable or in fertile ground,” she said.17

In addition, however, the Skillman Foundation emphasized the importance of the retirees. In her Hudson Institute presentation, Allen cited the modest pension levels, and that 46 percent of the retirees still live in Detroit.18 Allen appeared to find off-putting the notion that the grand bargain was focused on saving the Detroit Institute of Arts rather than protecting the pensions of retired government workers. Too many seem to talk about the museum as “the most important possession in our municipality,” Allen explained, whereas for the Skillman Foundation “it was really our people. It took us a while to get comfortable with the values of the grand bargain.” It seems, though, that the process resulted in the key institutions engaged in the grand bargain coming to see the importance of trying to keep the Detroit pensions as whole as possible.

To their credit, the foundations in Detroit’s grand bargain came to the bankruptcy issues with an “unprecedented urgency and seriousness,” as Silicon Valley Community Foundation CEO Emmett Carson described it, looking at the Detroit dynamic through an outsider’s lens.19 The Detroit issues were not typical, very complicated, and gave foundations such as The Kresge Foundation and the Ford Foundation—the two largest philanthropic contributors to the deal—little or no past experience to draw on for guidance. Carson sees the grand bargain as a great example of “being innovative,” “moving quickly,” and “serving a need”—all characteristics to be celebrated. Will the initial success of the grand bargain—in that it accelerated Detroit’s leap out of the stasis of bankruptcy—be a standard fixture in upcoming and future governmental fiscal crises, such as the ongoing troubles in Puerto Rico or the massive pension debt facing the city of Chicago?

Reviving Bankrupt Schools

As one bankruptcy took Detroit through its paces, another unfolded. A fiscal manager was in charge of trying to get the Detroit Public Schools (DPS) out of free fall, but without the option of filing a Chapter 9 bankruptcy petition to renegotiate or even wipe out significant portions of the school system’s debt. As of 2014, the DPS’s own unfunded pension liabilities had reached $1.2 billion.20 The system’s operating deficit as of the beginning of calendar year 2014 was close to $170 million.21

No one among Detroit’s philanthropic and community leadership minimizes the importance of fixing the schools—indeed, it is viewed as a crucial if not top priority for Detroit’s revival. It isn’t as if other cities have found the magic elixir for education that has somehow eluded Detroit, but Detroit’s challenges inextricably link education to poverty.

One observer who was very close to DPS challenges suggested that part of the problem—and the expense—of public education in Detroit was that the schools were compelled to do more than educate.22 Children would come to school in need of such basics as food, and even dental care—which would be added to costs, beyond those of other comparable public education systems, that the school system would have to absorb. Like some other cities, Detroit’s schools had become something of a competitive free-for-all, with a bevy of charter schools competing with traditional schools for students, and even engaging in aggressive advertising to skim off the cream from those institutions.

Neither Rip Rapson, president and CEO of The Kresge Foundation, nor Laura Trudeau, managing director at Kresge (and fully immersed in the follow-up to the grand bargain), minimize the importance of a DPS solution for Detroit’s future—but they recognize that not every foundation can be at the helm of every possible solution. Kresge’s emphasis, explained Trudeau, is to work on early childhood education issues—deferring to the Skillman Foundation to take the lead on education issues, added Rapson, with Kresge (and presumably others) prepared to “backfill” where Skillman leads.

If Detroit is to revive and, as part of that process, repopulate, it means creating or reviving a school system that can serve existing and future residents with children, as opposed to watching families leave the city when the challenge of schooling nears. In the aftermath of the grand bargain, two competing visions for the schools have emerged—neither one a panacea, and both with complexities and variations that will make the resolution difficult.

The Skillman Foundation was a prime mover behind the Coalition for the Future of Detroit Schoolchildren, whose thirty-page report was not short on controversy as the body deliberated, with the foundation’s CEO Allen serving as one of the Coalition’s five cochairs.23 The Coalition’s report describes a school system in governance chaos—a mix of traditional public schools, charter schools (rubber-stamped by as many as a dozen or so authorizers ranging from the city and the state to Grand Valley State University, Central Michigan University, and even Northern Michigan University—the latter some four hundred miles from Detroit), and twelve of the city’s worst-performing schools, administered by the state through the Education Achievement Authority (EAA). The Coalition recognized that “[w]hen so many are in charge, there is no accountability” (emphasis in the original).24

To recover from this “Wild West” system of school accountability, as the Coalition described it, the report called for an end to emergency management of the public schools and for a transition of the education system back to local control, with an elected school board. The Coalition calls for returning the oversight of the EAA schools back to the city, as well, and putting the charter schools under a regimen that establishes quality controls where little or none currently exist and limits the ability of authorizers to set up charter schools willy-nilly.

Following the Coalition report, Michigan Governor Rick Snyder announced his own plan for Detroit schools, with some elements that adhere to the Coalition recommendations—notably, an elected school board, but overseeing a new school district, the Detroit Community Schools, in charge of all elements and assets of public education but for the debt, which would remain with the old Detroit Public Schools.25 That debt would presumably have to be addressed by the state, so essentially this was asking state legislators in Lansing to vote to help the city that many have long seen as a financial albatross. How the new school district would function to bypass future indebtedness and to deal with the costs of educating a low-income, deprived student body isn’t clear. But, presumably, this structure would allow school fundraisers to address the problems they face in getting public and private support for the schools without having to encounter the cold shoulder they often get when the acronym “DPS” enters the discussion.

“If we can’t fix education, our recovery will be incomplete and short-lived,” the Skillman Foundation’s Allen said. She pointed out that the charter schools, for example, operate independently of the Detroit Public Schools—some presenting and marketing themselves as autonomous. She noted, however, that the current debates are first and foremost governance ones, with approaches to improving and guaranteeing the quality of education for Detroit school pupils not yet taking center stage in the restructuring of the city’s public education. Governance may have to be that necessary first step, because at this point there is no systemwide accountability for educational performance. With some public schools, notably charters, which are in theory parts of public school systems, “we are allowing people with public dollars to act in a private manner and…not for the public good,” Allen said.

Amid the tours of education reformers who have vaulted charter schools in Detroit into a virtual tie with traditional public schools vis-à-vis the number of pupils they have captured, Allen is raising a different issue—one of returning oversight to the people of Detroit who have long been disenfranchised by the school system and by the city government overall. The Coalition report, perhaps reflecting a Skillman Foundation value, proposes to hold all school types and all school management structures to the same standards of financial transparency—something typically resisted by freewheeling charter schools attempting to function as publicly subsidized private schools.

The grand bargain, whatever its strong points and shortcomings, has returned Detroit to a discussion of something that it gave up on long ago: the recognition that the residents of the city are just as capable of self-governance as anyone else. If Detroit is really going to emerge from bankruptcy, it is a bankruptcy of the public fisc and the public trust that must be overcome.

Restoring Democratic Functions

Why such attention to the role of foundations in “saving” Detroit from the depths of a debilitating bankruptcy? Steve Tobocman, former Michigan state representative and current executive director of Global Detroit, indicated that local government’s track record in tackling difficult problems hasn’t quite matched the quality of the philanthropic sector’s. No one in Detroit philanthropy is of the mind that they have had an unblemished track record themselves, but the devolution of Detroit’s governing structures has been a widely recognized issue.

Tobocman indicates that, having reached its nadir with the administration of now-jailed former mayor Kilpatrick, the problem of Detroit’s governance crisis was one of ethics. Who could be entrusted to function professionally, reliably, and ethically in confronting Detroit’s mammoth economic and neighborhood problems? In Tobocman’s opinion, what Detroit needs to do—and in some respects already is doing—as it backs up from collapse, is to rebuild “a new civic infrastructure” at the neighborhood level. He indicated that one step toward that end has been the change in structure of the city council, from at-large to district elections. As that change takes hold in the consciousness of Detroiters, residents will over time begin turning to district council members to press the city to function—and hold the council members accountable when it does not.26

For his part, Mayor Michael Duggan has begun restructuring municipal services to match the district outlines. Coterminous service and governance districts can potentially reenergize Detroiters to take responsibility for a municipal government that has spun centripetally away from their influence. Duggan’s approach is, according to some observers, meant to reconnect neighborhoods with services and local government with nonprofits. The Coalition’s school board recommendations are fundamentally proposals for restoring local control in education—wresting it from the state, from freewheeling charters, and from independent authorizers located across the state. Eventually, with respect to both city hall and the schools, the trajectory of recovery has to involve a revival of local self-governance, else Detroit remain as it has been in its history: a city dominated by corporate interests and their political partners—albeit with a new set of corporate power brokers replacing the automobile-manufacturing elites of the past.

Part of that picture has to be a revival of the nonprofit sector, particularly as regards community-based nonprofits, that includes carrying the voices of communities outside of political processes but to political leaders—for them to listen and learn what the communities want, need, and are prepared to do. What the nonprofit sector is able to do, according to the Michigan Nonprofit Association’s Murray-Brown, is to bring the discussion home of Detroit as a divided city. This can be done by courageous community leaders, backed by an organizational infrastructure, who will pursue solutions addressing racial equity.

That requires, says Sarida Scott, executive director of the Community Development Advocates of Detroit (CDAD), real, substantive community engagement, not simply sitting at the table to hear and nod. Prior to and during the grand bargain, there were extensive outreach efforts to bring community people to the table, but many community activists, like Scott, don’t appear to be much impressed. Both The Kresge Foundation’s Rapson and Global Detroit’s Tobocman suggested that one shortcoming in the first rounds of community engagement was an overemphasis on the planning process and a corresponding lower level of attention to engagement around implementation. Planning for the Detroit Future City (DFC), according to Kresge’s Trudeau, is now focused on implementation and on establishing DFC as an entity independent of the foundations, and, consequently, more authentically able to emphasize community perspectives and priorities.27

Democratic process is one of the consistent issues that critics of the grand bargain raise. A foundation executive who possesses the same kind of bifurcated identity as Murray-Brown (and like her, with a father who is a pensioner in the city) expressed just that concern about the grand bargain. He cited the oft-repeated charge of Frank Hammer, a former General Motors worker and union activist, that the grand bargain was a “bloodless coup d’état.” Because, despite the election of Michael Duggan as mayor, in the post-bargain governance of Detroit the city’s finances will be overseen by a nine-member Financial Review Commission appointed by Governor Rick Snyder, in addition to two state officials (the state treasurer and the state budget director) and the president of the Detroit City Council.28 A foundation executive who declined to be identified for this article characterized the commission as “not just undemocratic, but plac[ing] the city and residents in a no-win position,” and described community engagement in big foundation-supported initiatives, such as the M-1 light rail line, as an “afterthought.”

Detroit foundation executives like Rapson and Trudeau hardly disagree. While they are admittedly retooling their efforts in community engagement, they are not starry-eyed in the slightest or under the misapprehension that their number counts of people attending Detroit Future City planning meetings constitute a revitalization of democracy in Detroit. Moreover, the challenge in large measure comes down to the ability of the nonprofit sector to ensure that it not only is sitting at the table but also is enabled to plan in partnership with city, state, and foundation leaders. Tobocman suspects that, at least for the moment, foundations have not been adequately informing local nonprofits of their contributions to the grand bargain and that they are tapped out for the kind of support community-based nonprofits need in order to be full partners. Whether that holds for the midterm and long-term future remains to be seen; but, to an extent, the grand bargain may have cemented some support for Detroit-based nonprofits from national foundations such as Ford—the grand bargain’s largest philanthropic contributor—that will continue for some time (especially in Ford’s case, due to the recent revision of its mission to focus on social justice). There could hardly be a more immediate and poignant case for philanthropic investment in social justice progress than the dynamics of post– grand bargain Detroit; nonetheless, the foundations will need to keep their eye on building up Detroit’s tattered nonprofit infrastructure, and the nonprofits will need to be attentive to the foundations’ postbargain grantmaking.

Another problem is the precedent the grand bargain sets regarding the role of foundations in society. Writing for the Detroit News, Daniel Howes, Robert Snell, and David Shepardson asked, “Could foundation leaders, governed by independent boards hewing to individual missions, persuade their boards of directors to participate in what would amount to a private-sector bailout of the city’s pensions? Would the fund drain foundation dollars committed to fighting blight, rebuilding infrastructure and supporting critical social services needs?”29 In his own column, Howes wrote, “Every foundation dollar that goes into a fund designed to protect the DIA by supporting pension obligations for city retirees is a dollar that doesn’t go to support downtown redevelopment; to bankroll construction of the M-1 rail line; to finance blight removal and new public safety equipment; to bolster the DIA’s annual fund, endowment or both.”30 It is a legitimate concern, so long as there is recognition that Detroit’s emergence from bankruptcy must address a deficit of democracy as well as deficits in the city’s and the school system’s operating budgets.

There is always plenty going on to give substance to fears of a “bloodless coup” partnership between corporations, foundations, and the state government. For example, Marti Kopacz, the bankruptcy court’s expert on Detroit’s financial issues (hired to provide a perspective independent of the emergency manager’s and the creditors’) was quoted by Bloomberg Business as having said in an interview, “As a society, we believe in democracy, but there comes a time when the political machinery simply fails…. Once control goes back to the electorate, you are going to run the risk they could elect somebody that is not as capable.”31 No less disturbing to hard-pressed Detroiters has been an element of insouciance in the behavior of the executives and governing body of the Detroit Institute of Arts, which was saved from being sold off piecemeal to pay off the city’s deficits. In October 2014, the DIA awarded its executives pay raises and bonuses (accompanied by justifications that could only have been received as tone-deaf by a bankrupt city occupied by thousands of retirees whose pensions had been shaved).32 Just as confusing to Detroiters was the news that the DIA was considering auctioning (or “de-accessioning”) some paintings—notably, a Vincent van Gogh still life—after the museum had taken the strong position during the bankruptcy proceedings that selling even one piece from its collection in order to satisfy creditors and pensioners would be devastating for the museum’s standing and credibility.33

Remembering True Detroiters in a Regional Context

“Democracy for whom?” might be the appropriate question. Nearly everyone involved one way or another with Detroit’s future echoes some of the concerns of the Reverend Charles Williams II of Detroit’s Historic King Solomon Baptist Church: that the poverty and unemployment of most longtime Detroiters may not be a high priority for many decision makers.34 For some, the issue isn’t poverty per se but the notion that long-term Detroiters do not feel that they have been beneficiaries of the putative revival of the city.

The national press has been focused on the revival of the Midtown area (the stretch of Woodward Avenue north of Detroit, anchored by historic homes plus anchor institutions such as the Detroit Medical Center, Wayne State University, and the Detroit Institute of Arts) and Detroit’s Downtown (where Quicken Loans mogul Dan Gilbert has purchased some eighty office buildings at rock-bottom prices as their headquarters, moved thousands of Quicken Loans employees to the area, and stimulated the growth and expansion of IT business ventures). While everyone acknowledges a sense of street life in Midtown and Downtown that hasn’t been seen in several decades—including an explosion of restaurants and young white professionals walking their children in strollers or jogging after work along Detroit’s broad thoroughfares—everyone is also aware that Midtown and Downtown are a tiny proportion of Detroit’s physical footprint. The hundreds of thousands of residents who still live in the neighborhoods often feel that the Midtown/Downtown dynamic has left them out—and indeed may not have been intended for them in the first place.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

The issue is one of both longtime residents and race, in that Detroit’s longtime population is in large majority black, and the newcomers are not. CDAD’s Scott notes that the Midtown/Downtown revival has sparked a debate over the effects of gentrification and the message it sends to longtime Detroit residents who stayed—some because of a lack of alternatives but others because of their dedication to home and community and a desire to see things through.35 Tobocman views the Downtown and Midtown “environment for the business sector” as “never having been stronger” in his twenty years of working in Detroit; but he says it would be “hard to argue that for the majority of Detroiters who live in low-income neighborhoods there aren’t some significant challenges that exist.”

Both Scott and Tobocman are concerned about divisions among Detroiters—those who are excited by the new commercial and residential development dynamic and those who feel left behind or left out. Scott wonders “how to achieve inclusion and equity without pitting groups against each other—white and black, old and young…the new versus the old.” Despite her position as a community advocate arguing for a modification in the grand bargain dynamic that would not further dispossess and disenfranchise long-term Detroiters, Scott expresses a reluctance to “feed into anything that feeds into more division in Detroit.”

The problem goes back to the multiplicity of plans for neighborhood revival that Detroit has witnessed over the years with little evidence that they have had much or any positive effect—except on Midtown. Having grown up in Detroit, john a. powell, professor at the University of California, Berkeley, and director of the Haas Institute for a Fair & Inclusive Society, knows the challenge and explains it succinctly: “Any sociologist will tell you it is hard being poor. But it’s harder being poor in a poor neighborhood. And harder still being poor in a poor neighborhood in a poor city. And yes, it’s hell to be a poor family, in a poor neighborhood, in a poor city, in a poor state!”36 His recommended framework for Detroit solutions is aimed fundamentally at the needs of longtime Detroiters:

We need to really understand relationships, not just things in isolation. We cannot focus on transportation or housing, but need to look at the relationship between transportation and housing. Or even between transportation, housing, jobs, and schools.

We have to think of the levers that actually move the system and be very deliberate about making sure that these systems actually benefit marginalized communities. To do that you have to make sure that marginalized communities have a voice and an input.

I’m not talking about redistribution or handouts but about bringing folks into the system in a healthy way, so that they contribute to the health of the system. It is crucial to growing and sustaining opportunity for the entire community.37

Such visions may represent the most difficult challenges for Detroit’s community of nonprofits, foundations, and citizen organizations working toward a fair and just revival for the city. powell’s framework is straightforward in its elements but difficult to translate into concrete programs and actions, and many see the Gilbert scenario as repopulating vacant buildings with an outsider workforce of Quicken Loans and other IT-industry employees who ideally would end up as residents. Another idea—taking huge tracts of vacant land in Detroit for reuse as urban farming or other alternative uses—has a similarly outsider feel (even if the activities draw and employ some existing Detroiters), particularly with the visible roles of young white entrepreneurs in these urban innovations.

While it may not be evident to external observers reading about the Downtown and Midtown revival that takes up a good chunk of Detroit’s media attention, most insiders recognize the true need for reviving Detroit by helping and boosting the jobs, incomes, and living conditions of longtime Detroiters. This came up as an issue in a report by Philamplify (an initiative of the National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy [NCRP]) on The Kresge Foundation. A consistent theme in the NCRP recommendations for Kresge addressed a need “to continue recent efforts to forge relationships with neighborhood and nontraditional leaders to develop a more inclusive understanding of potential partners and levers for social change.”38 Understanding the need to reach existing Detroiters is one thing, but the avenues that work are often difficult to discern in the midst of conflicting and sometimes contentious agendas.

Rapson doesn’t dismiss the importance of the Downtown and Midtown revivals, suggesting in fact that they have been “a little kicked around of late” but have created a “street-life vitality” that “sends a different signal to the markets” about the potential of Detroit’s revival. Viewing the challenge of reaching existing Detroiters through the lens of what philanthropy might do, Rapson offers a six-point agenda:

- “[Try] to create an environment that is conducive to investment in the neighborhoods”;

- “Reform…the public education system”;

- “Take the M-1 (light rail) system to the next level (to be a regional system)…to connect Detroiters to jobs”;

- Employ a “suite of mechanisms that help accelerate the conversion of blighted and abandoned land”;

- [Effect] large-scale conversions of blighted and abandoned areas to “mixed-income, mixed-use areas of opportunity…places that will attract new and existing residents”; and

- Revive neighborhood commercial spines that will be places where residents want to live and shop.39

Within those six items, there are two themes that crosscut most of them and may bedevil Detroit’s philanthropic supporters and governmental planners. One is the crafting of specific strategies for the commercial strips of existing neighborhoods that have not been beneficiaries much or at all of the investment into Downtown. Rapson sees evidence for commercial strip revitalization in efforts already underway along Jefferson Avenue, toward the east side of Detroit; in southwest Detroit, where Latino immigrants have regenerated a sense of neighborhood as place; and along Livernois Avenue, in northwest Detroit, where there are efforts to revive the commercial strip, capturing its old identity as the “Avenue of Fashion.”40

It was once somewhat axiomatic that neighborhood development strategies had to focus on the revival of neighborhood housing, after which the lagging dynamics of commercial strip revival would follow. In places such as Detroit and other troubled cities (think Baltimore and Newark), there has been a recognition that the sequence must be reversed—or, if the neighborhoods are to be sustained, the commercial spine must be well supported. Rapson draws on his experience with the Minneapolis Neighborhood Revitalization Program, which made commercial spines essential building blocks of neighborhood plans in areas such as Stevens Square (Nicollet Avenue) and Sheridan (the 13th Avenue corridor). However, the Minneapolis Neighborhood Revitalization Program emerged from a sense of impending decline in Minneapolis’s older, working-class neighborhoods—hardly comparable to the devastation and depopulation of Detroit’s.

Kresge’s Trudeau, and others, cited a broadening appreciation for the need to invest in commercial strips where there is a “critical mass” of activity beginning to emerge—reflected in the visibility of Mayor Duggan’s “Motor City Match,” which awards $500,000 in grants every quarter to a mix of building owners and business owners in the neighborhoods who are bringing forth business opportunities in need of jump-start capital investment.41 The first match grants, ranging from $10,000 to $100,000, were announced in October of 2015.42 (Over a twenty-year period in Minneapolis, from 1991 to 2011, the Minneapolis Neighborhood Revitalization Program invested over $10 million in commercial strip improvements in neighborhood commercial corridors.43 It isn’t really known what it will take to make a critical investment in commercial corridor revival in Detroit’s neighborhoods given that, for most, the conditions and the markets are significantly less stable than were Minneapolis’s a quarter century ago.)

The other crosscutting theme in Rapson’s six-point plan is one of connecting or reconnecting Detroit with the counties of southeast Michigan. The division between the city and the suburbs has been a matter of socioeconomic status and race. It would not be too much of a stretch to suggest that Macomb County, Oakland County, and the parts of Wayne County that are not Detroit may send employees and executives to the General Motors offices at Renaissance Center, but Detroiters have been largely disconnected from jobs in the counties. The breakdown has been symbolically reflected in the structural disconnects between the bus service of the Detroit Department of Transportation (DDOT) and the Suburban Mobility Authority for Regional Transportation.

Critics have dismissed the M-1 light rail line, strongly supported by The Kresge Foundation and by Detroit investor Roger Penske, as a limited kind of streetcar to benefit travelers up and down the Woodward corridor—basically connecting New Center (where the Amtrak station is) to Midtown to Downtown. The connections to the neighborhoods and to the ability of Detroiters to connect to jobs in the suburbs are not immediately evident, giving rise to comparisons of the M-1 system to the relatively little-used Downtown Detroit People Mover (a single-track system reaching a small area of Downtown, originally meant to have some sixty thousand to seventy thousand daily riders—ten times the actual number of users). Rapson and Trudeau are both adamant that if the M-1 is simply a 3.3-mile streetcar, then the plan will have fallen vastly short of what it should do.

The M-1 consortium was able to secure passage of state legislation creating a Regional Transit Authority charged with producing a regional transit plan for Southeast Michigan. Funding for that system must be approved through referenda appearing on the ballots of the region’s four counties. The regional authority has been vested, therefore, with the ability to tax not just Detroiters, who are already always hit, but also residents of the suburban communities. Rapson and Trudeau believe that regional buy-in will be difficult—hardly a slam dunk with the voters.

The regional dimension of Detroit’s recovery may be the untold story, but it is central to the narrative offered by Kevyn Orr, the Jones Day attorney who was appointed by Michigan governor Rick Snyder as Detroit’s emergency manager for the bankruptcy. The region, Orr notes, was created in a way to be divided by what he called “caste, class, and race,” going back to decisions made by Henry Ford to prevent black employees in his factories from living in suburban Dearborn, restricting those who were able to move from Detroit to residences in Inkster. As the epitome of racial segregation from the wealthy white suburban communities, Detroit found itself over time simply unable to rescue itself.44

To Orr, a large part of Detroit’s steps toward recovery has been the strategy of getting the region if not the entire state to commit to Detroit. Among the elements he ticks off as examples of that broader commitment are Governor Snyder’s “all in on Detroit” tactic through the bankruptcy (sometimes against the advice of his advisors and in the face of hostile state legislators) and into the grand bargain, where the state put up a significant sum; the regional water authority being able to build on revenues that are likely to be three-fourths suburban; the M-1 light rail becoming part of a regional system; suburban buy-in to the grand bargain being enabled through the Detroit Institute of Arts; and, notably, participation of private foundations located in the suburbs, like Kresge in Troy, or entirely out of state, as in the case of Ford.

A regional conception of Detroit’s getting through the bankruptcy cements part of the suburban community to Detroit’s future and, as Orr notes, reflects the fact that as southeastern Michigan goes, so goes the state. But maintaining that suburban commitment requires something more than an intellectual appreciation of the symbiotic relationship of city and suburb. Orr outlines a number of factors Detroit needs in order to sustain its revitalization trajectory:

- Leadership. As Detroit declined over the decades, when the city needed (in Orr’s words) “sober, honest, visionary leadership,” it didn’t get it. The sober/honest description is generally the opposite of what happened under now-imprisoned former mayor Kilpatrick. Like Rapson and Trudeau, Orr appears confident in Mayor Michael Duggan, elected as a write-in candidate, who he hopes will bring the kind of sober leadership to Detroit that he believes political leaders brought to Miami after the Liberty City and Overtown disruptions (when many people had written off that city).

- Talent. Orr’s reference to talent partly emphasized the institutions such as Kresge, Ford, and others that were “making a bet on the city” and putting their human resource talent, abetted by capital, at the disposal of the city. But the need is for governing talent, too. Detroit’s city government has been dysfunctional for so long that many city officials had bought into a governing culture of failure, to the point that things not happening was more reliable and comfortable than the risk of trying to make progress. For Detroit to function competently within the region and with the state, it has to display the competence that so many successive city administrations in Detroit have not.

- Transparency. Orr takes pride in having pushed for “telling the public the true state of affairs” when it came to the reasons for Detroit’s slide into bankruptcy and the challenges for clawing a way out. For Detroit residents who have long been fed the fantastical ideas that successive initiatives were “the” answer to the city’s problems, Orr’s approach was just the opposite: explain exactly how bad things are, let that settle into people’s consciousness, and then craft answers that deal with the realities.

- Cooperation. Even within the city, there were multiple bargaining units representing city employees (uncoordinated city agencies and departments), a division between the city council and the mayor’s office, and the obvious disconnect with the region. Without the ability to work through the complexities of the Detroit political and social dynamic, the basis for long-term solutions would be just about impossible.

- “The residents who stuck it out.” Orr’s point returns the narrative to the central issue of providing help and support for the residents who chose not to leave as the city fell apart around them. In part, the answer for longtime Detroiters is the provision of public safety and health services, public works, parks and recreation, planning and zoning functions, and competent revenue-raising and use—all the core functions that the city had allowed to languish and disintegrate.

That still leaves a city of hundreds of thousands of impoverished people who merit more for their dedication to their neighborhoods than simply basic municipal services. Detroit is replete with residents who, in the absence of competent government, mowed the grass on vacant lots, did their best to pick up trash in public parks, and did what they could to take care of each other when public and private authorities proved themselves unable or unwilling to do so. But a strategy that helps those people as much as the city has jump-started activity in Downtown and Midtown remains elusive—even for most of the key players in this city drama.

Some, like Ponsella Hardaway of the Metropolitan Organizing Strategy Enabling Strength (MOSES), also get the regional dynamic at play. Hardaway did some back-of-the-envelope calculations of employment to point out how many Detroiters are not among the 53,000 or so who live and work in the city, and the 150,000 or so who leave the city for their daily jobs: perhaps 80,000 or more, who are simply unemployed and isolated. She contends that there are jobs in the southeastern Michigan region that Detroiters cannot get because of transportation difficulties and racial barriers. In her view, the challenge is finding equitable development strategies that connect Detroiters to jobs in the region and, to the extent that they emerge from major projects, in the city itself.

Hardaway cites a Wayne State University professor, Peter Hammer, who has written some major critiques of shortcomings in the city’s post-bankruptcy “plan of adjustment” that fail to take into consideration issues of race and regionalism. Despite Orr’s contention that the process launched by the grand bargain contains a significant agenda toward regional equity, Hammer wrote, in a critique for the bankruptcy court, “A feasible Plan of Adjustment based on reasonable forecasts and projections must be assessed in light of the City’s history of still unhealed racial conflict and the City’s position within a fractured and segregated regional economy.” He continued:

[A]ny legitimate analysis of the Detroit Bankruptcy and the City’s Plan of Adjustment must be situated in the context of the Three R’s—Race, Regionalism and Reconciliation…. I am deeply disappointed by the neglect of these issues in the Expert Report. The Report is a word-searchable pdf document. Nowhere in the document are the words “race,” “racism,” “discrimination” or “segregation.” While the phrase “white paper” appears twice, the phase[sic] “white flight” does not appear at all. These are the root causes of Detroit’s current financial crisis and yet they are completely absent from the report. The Report looks at the root causes of failures of generic IT Systems, but never once examines the root causes of the fiscal crisis underlying Detroit’s municipal distress….

There is no discussion of an eighty-year history of discrimination, segregation, racial tension and white flight producing a dysfunctional region. There is no discussion of how economic markets nested in a hostile and highly fractured geopolitical space fail to thrive. These are the core forces that produced the Bankruptcy, yet they are not recognized in the Expert Report at all.

One has to try hard not to see the effects of these forces on the physical landscape of Southeast Michigan. Detroit is a city where nearly 40% of the population lives below the federal poverty level, yet it sits in a region that is defined by its relative wealth and prosperity. The Michigan Roundtable and the Kirwan Institute [for the Study] of Race and Ethnicity at Ohio State have conducted “opportunity mapping” of the region. “Opportunity,” defined by a metric reflecting the quality of housing, education, employment, health care, transportation, and civil society, can be assessed and given a colored representation on a map of Southeast Michigan…. What becomes obvious from the map is that there are high levels of opportunity in the region and low levels of opportunity in the region and that these areas are spatially segregated. One can almost see the outlines of the geopolitical boundaries of Detroit and Pontiac as defining the lowest levels of opportunity in the Region. When one overlies spatial mappings of race on top of the mapping of opportunity, one sees that[sic] a region completely segregated in terms of both race and opportunity.…This is the core of what john powell terms “spatial racism” in modern America. Detroit is ground zero for spatial racism.

Detroit remains one of the most racially and economically segregated regions in the country, yet there is no trace of this realization in the Expert Report.45

Hammer’s critique decries the bankruptcy court expert’s (and the city’s) emphasis on buildings and property (including a large commitment to expensive demolitions), and suggests that an investment in human capital is needed: “What would be the economic benefits of investing comparable amounts in people—building human capacity—head start, schools, reducing health disparities, citizen re-entry, job training and economic opportunity?,” he asks. “Even in a narrower economic frame, we need to ask what would be the differential in economic benefits of spending comparable funds in foreclosure relief designed to keep people in their homes, as opposed to demolishing those same homes after the residents have been forced to leave.”46

Many of the residents who haven’t left Detroit are seniors. Vincent Tilford, until recently the executive director of Habitat for Humanity Detroit, and now the executive director of the Luella Hannan Memorial Foundation, speaks with knowledge about older Detroiters because the foundation is an operating one that provides housing and services to seniors in metro Detroit. He explains that many of Detroit’s homeowners are seniors, living in homes showing the wear and tear of deferred maintenance and, as public sector retirees in many cases, now living with less income to repair and upgrade their properties. Many are facing tax foreclosures, which, if the city does foreclose or sells tax notes to third parties, will lead to massive displacement of some of the most dedicated and stable residents of the city. Tilford and others describe the city’s efforts to provide zero-interest repair loans to older homeowners, but their limited incomes make taking loans difficult.

Moreover, Tilford noted, “When I talk to older adults about the M-1 rail line, they say, ‘This wasn’t built for us, it was built for other people moving here.’” Perhaps the M-1 and other initiatives are meant to help longtime Detroiters—but if so, Tilford says, “it has to be communicated better and differently.”47

Both Tilford and the director of the Detroit program of the Local Initiatives Support Corporation, Tahirih Ziegler, observe that there are other dynamics occurring that could further displace rather than help existing Detroit residents. On top of the prospect of a tax foreclosure of tens of thousands of homes, Tilford and Ziegler express concern about rental developments with expiring federal subsidies. If the subsidies are allowed to expire without financial and regulatory intervention by local authorities, “the residents,” in Ziegler’s words, “will have to move.” For a city whose population has been in a free fall for decades, to fail to intervene to stabilize the conditions for those who fought back and stuck it out would be a tragic outcome.

Charting a Course

The fact that the Detroit fiscal vortex has left players scrambling with multiple aspirations and plans but challenges in translating them into action shouldn’t be surprising. The expectation that there are easy answers waiting to be discovered goes against logic and history. Societal problem solving is incremental but hopefully moves toward solutions that in their design and implementation lead to systemic changes. On the ground, the observers who think that the grand bargain might have devoted too much attention to the pension bailout and an elite arts institution are sometimes at a loss to offer concrete next steps except for improvements in process—and solutions that are offered for what ought to happen next are often thin and tentative. The problems of Detroit, even as reflected in the hundreds of pages of the Detroit Future City plan, are large and daunting—so big and so deep-seated, so multifaceted and interrelated, that it is difficult to chart an action strategy that moves the city from the edge of collapse and toward sustainable recovery.

Talking to a variety of philanthropic and nonprofit leaders surfaced some clear directions that are often included in official reports but are sometimes hard to discern:

1. Rebuild the civic infrastructure. CDAD’s Scott complains about the loss of democratic process during the grand bargain negotiations and the postbargain follow-up. Even Rapson and Trudeau recognize that the organizing and outreach process during Kresge’s leadership of the Detroit Future City plan and during the grand bargain negotiations needs recalibration. “If the essence [of criticism of the community engagement process] is that over time the community needs to figure out appropriate ways to make its desires known and become involved in a meaningful way in the decision-making process,” Rapson said, “I couldn’t agree more.” The essence of his agreement is that meaningful civic participation has to lead to each “microinitiative” in which the city—and Kresge—are involved, being “infused” by community decision making that is sustainable. Trudeau noted that the next phase of civic engagement in the Detroit Future City effort is the development of an independent entity that is not controlled by or responsible to The Kresge Foundation. They are all struggling with trying to find authentic mechanisms for civic engagement, but the critics feel that community residents—even if included in the multiple meetings convened by the foundations—have been the “objects” rather than “subjects” of the participation process. In terms of the city’s and the foundations’ upcoming engagement processes, Trudeau’s recognition that the next stages have to be “more intentional” is obvious.

Nonetheless, behind committees, task forces, and focus groups that may be created to advise components of the Detroit recovery—even if they are given nominal “independence”—must be support for the indigenous community-based organizations that are governed by and represent Detroit’s neighborhoods. That includes groups like MOSES and other community organizing efforts, as well as local community development corporations and human-service advocacy groups. Were it not for community-organizing groups, the plight of the low-income households that were hit by devastating water bills in 2014 and 2015 might not have been noticed or addressed. Part of the challenge of building and sustaining that infrastructure falls to the foundation community, which needs to keep in mind that its commitment to building a civic infrastructure means providing funding for those community-based organizations; and part falls to intermediary organizations, which need to closely monitor the array of groups that are tackling community problems on their own. Too many groups seem to have struggled because they fell into the trap of investing too much of their program portfolios in housing when the housing market was unbelievably weak, and needed to alter their business models. Others have been too small or have been trying to serve shards of neighborhoods—unable to sustain operations, and compelling mergers with stronger groups. The foundations and intermediaries have to be focused on sustaining indigenous organizations that can survive in the long run.

2. No more funding for Midtown and Downtown. The revival of the Downtown area, largely financed by business moguls like Dan Gilbert, and the investment in Midtown, attracting a young, “hip” population, needs support—but not from the philanthropic sector (at least, no longer). The disinvestment by private and public sources in neighborhoods throughout the city needs to be rebalanced and rectified by a major shift back to the neighborhoods. That means bringing municipal government resources such as the city’s Community Development Block Grant (CDBG) program dollars back to neighborhoods, with an eye toward leveraging private capital from banks and foundations. For example, the use of foundation grants to write down the repair costs of existing homeowners who want to engage in home rehabs is necessary, given the very-low-income population of homeowners and renters. Investors in Midtown and Downtown have access to the private capital markets and to federal subsidies that neighborhood people simply do not. As put by Timothy Thorland of Southwest Housing Solutions, one of the recognized well-run community-based organizations, “the private financing market can take care of the financing needs of Midtown and Downtown. It doesn’t have to be the ultimate priority that it was years ago.” He added, “Whether it’s the mayor, Dan Gilbert, or foundation executives, now is the time to invest in neighborhoods.”48

3. Explore commercial strip and anchor institution development strategies. Rapson’s suggestions for commercial strip revival strategies make sense—not only for neighborhood stabilization but also for business development by Detroiters. Tilford noted that the bulk of the Motor City Match awards did go to businesses created by Detroiters, but the strategy has to expand to include anchor institutions. Think of the Midtown development strategy linked to the presence of anchor institutions such as the Detroit Institute of Arts, Wayne State University, the Henry Ford Hospital, and more. There are anchor institutions that should be seen as nodes for development activity in viable neighborhoods across the city—notably churches and schools. Both schools and churches are important symbols in black communities and should be actively explored as venues for developing critical masses of investment activity in neighborhoods.

4. Negotiate community benefits agreements (CBAs). Hardaway and Scott both point to the possibility of the city’s negotiating “community benefits agreements” for major projects that involve the use of public funds. (Scott’s organization, CDAD, has been an active advocate for a CBA linked to the proposed construction of a new arena for the Detroit Red Wings.49) The argument that the city and developers use is that the market is too fragile to support the imposition of a community benefits agreement. Every city tied to private developers resists exactions, but what would a community benefits agreement require? In a situation like Detroit’s, the likely components might include a “first-source hiring requirement” that obligates the developer to look for local residents to fill construction and permanent jobs, if feasible; to provide job training for potential workers; to set aside a portion of commercial space for local businesses; and to contract for local community-based organizations to work with local residents impacted by the developments. Detroit has had discussions of CBAs potentially attached to large-scale projects with significant subsidies, a concept promoted by Rashida Tlaib, a former Michigan state representative, more recently director of the Sugar Law Center for Economic and Social Justice.50 The Sugar Law Center, operating with support from the Ford Foundation, Local Initiatives Support Corporation (LISC), and the Equal Justice Center, suggests specifically that the following might be the benefits embedded in a CBA:

- Access to job training and job opportunities created by the project;

- For local small businesses, access to service and supplier contracts for the project;

- Environmental protections from health risks created by construction and project activities, such as diesel exhaust, dust, and others;

- Minimized housing and local business displacement;

- Sustainable practices on the project leading to improved quality of life and empowerment of the local community; and

- Other improvements targeted to the goals of the particular project and needs of the involved community.

If opportunities for CBAs go by the boards because of city government and private developer fears of market weakness, the community loses. CBAs are one way of making sure that Detroit’s “off the brink” development generates specific, direct benefits for Detroiters, as opposed to counting on indirect multiplier benefits.

5. Protect existing residents. Scott says, “The problem we have in Detroit, people want to use gentrification synonymously with development.” The underlying issue is that some of the revitalization dynamic in Detroit could lead to population turbulence and displacement. Pushing more Detroiters out of the city involuntarily—to join those who voluntarily fled the city because of lack of police and fire protection, trash collection, and streetlights—is exactly the wrong signal to send to the markets and to the American population. The impending municipal tax foreclosure of an estimated twenty-five thousand properties should be halted. It is no exaggeration to suggest that “mass evictions” of homeowners and tenants could ensue if the tax foreclosures proceed.51 The continuing dynamic of mortgage foreclosures needs to be stemmed in part with an agreement with lenders and servicers to keep people in their homes. The rental properties that have expiring federal subsidies such as Low-Income Housing Tax Credits should be recapitalized, as Ziegler and Tilford indicated. More broadly, given the likelihood of a potential gentrification dynamic in various subareas, the city needs to work with community development organizations to generate an antidisplacement strategy that will minimize and mitigate displacement pressures on lower-income tenants and homeowners. The alternative is a population outflow that sends the message that Detroit’s revival will give little or no consideration to the people who have been the courageous mainstays of the community despite their having been let down by dishonest politicians and disinvestment-minded private-sector actors.

6. Double down on regional contributions. Hammer’s analysis that strategies that don’t capture and capitalize on financial support from the region basically let the suburban counties off the hook is quite persuasive. Detroit needs to be thinking about approaching many of its challenges on a regional basis, as opposed to going it alone. That doesn’t absolve Detroit and Detroiters from doing all they can and must do to put the city on the right track, but the mayor and the governor have to be strongly committed to maximizing regional commitments and competition. The pivot has to be to turn the Detroit metro area into “something worth fighting for, rather than fighting over,” to use the words of Bruce Katz and Jennifer Bradley, authors of The Metropolitan Revolution: How Cities and Metros Are Fixing Our Broken Politics and Fragile Economy.52

7. End the messiah complex. From Kwame Kilpatrick to Dan Gilbert to Michael Duggan—there is a sentiment among some in Detroit that emphasizes the need for a heroic leader who will guide the city out of its morass. Hammer’s letter slams the bankruptcy court’s expert for the report’s “indulgence of the ‘great man’ theory of history.” He contends that because the plan that would take the city out of bankruptcy “fails to identify the root structural causes of the crisis and implement necessary structural reforms, one must invent a hero to single-handedly rescue the City from the current crisis, if there is to be any hope.”53 Duggan frequently gets painted into the “great man” role, particularly by the foundation leaders, who have found him a valued collaborator and competent leader after so many decades of disappointing city hall performance and follow-through. He may be a good mayor, but he is a temporary occupant of the office. Detroit’s long-term sustainable trajectory toward recovery isn’t going to be solely Duggan’s success or failure, nor the sole responsibility of Gilbert, Penske, or Michael Ilitch, nor Kresge’s Rapson or the Ford Foundation’s Darren Walker. Where Detroit’s recovery is concerned, there is no magic bullet and no magician possessing all the answers.

…

The current generation of plans—notably the Detroit Future City plan, guided and supported by The Kresge Foundation—is, in the foundation’s own words, a “framework” for Detroit’s future: identifying potential jobs, alternative uses of vacant land, development of parks and other green spaces, and different conceptions of future neighborhoods in the city.54 But, according to Tobocman (with an analysis shared by others), the Detroit Future City process suffered from a “lack of focus on implementation, which has come to haunt them.” When a planning process transitions to implementation, generic agreements reached among diverse parties—even with the extensive outreach mounted by Kresge—fall prey to divisions that might be excited by the potentials and divisions fearful of what might happen to them and their neighbors as a result of forces not under their control.

As Tobocman describes it, “There are 700,000 residents, there are 700,000 Detroit stories—they’re all true and all equally valid.” The one overarching story should be how Detroit’s recovery from decades of misery protects the people most in need. Despite new trendy restaurants, joggers along Woodward Avenue, the “creative class” moving to Midtown, and a young IT workforce taking residence Downtown, if Detroit’s future is one in which the low-income population is displaced due to what might be the nation’s largest municipal tax foreclosure in history, others are penalized with unjustifiably burgeoning water bills, and still others are pushed out by the laissez-faire position that gentrification is an indicator of progress, then Detroit’s turnaround will not be a renaissance story, or even the tale of an historic bargain—that is, unless the bargain were the proverbial pact made with the devil.

*The contributions of Ford, Kresge, Kellogg, Knight, Davidson, Community for Southeast Michigan, Mott, Erb, Hudson-Webber, and McGregor will be administered through a new 501(a)(3) supporting organization called the Foundation for Detroit’s Future.

**Dedicated to offset healthcare cuts for city retirees in the pension aspect of the bankruptcy.

***$5 million of the $10 million is contingent on the Detroit Institute of Arts raising $100 million.

****Dedicated specifically to helping the Detroit Institute of Arts with its transition to nonprofit status.

*****Dedicated specifically to helping the Detroit Institute of Arts with its transition to nonprofit status. (Table does not include all corporate contributors.)

Notes

- Donna Murray-Brown, in an interview with the author, October 15, 2015.

- Josh Sanburn, “This is the Poorest Big City in the U.S.,” Time, September 17, 2015; “Detroit, MI Unemployment Rate,” YCharts.com, accessed October 20, 2015; and Keith A. Owens, “Detroit unemployment remains more than twice level of state, nation,” Michigan Chronicle, July 28, 2015.

- Michael J. Rich and Robert P. Stoker, “Governance and Urban Revitalization: Lessons from the Urban Empowerment Zones Initiative” (paper presented at the Conference on a Global Look at Urban and Regional Governance: The State-Market-Civic Nexus, Atlanta, Georgia, January 18–19, 2007).

- Robin Boyle and Peter Eisinger, “The U.S. Empowerment Zone Program: The Evolution of a National Urban Program and the Failure of Local Implementation in Detroit, Michigan” (paper presented at the EURA Conference, Copenhagen, May 2002).

- William J. V. Neill, Urban Planning and Cultural Identity (New York: Routledge, 2004), 199.

- The 4.5 percent reduction is the average. The specific impacts on each retiree will vary depending on a number of factors, so that some retirees could actually experience larger pension reductions and others smaller ones. Retired police and fire personnel, for example, will receive smaller cuts due to their pensions having been better managed.

- “Schuette to Respect Vote by Detroit Pensioners to Waive Constitutional Protections, Support Grand Bargain,” State of Michigan Attorney General Bill Schuette’s website, July 21, 2014.

- Anne VanderMey, “Detroit pensioners approve bankruptcy haircut in landslide,” Fortune, July 22, 2014.

- Editorial staff, “Retire the stereotype of the six-figure public-sector pension, say academics,” Retirement Income Journal, October 20, 2011.

- Khalil AlHajal, “Detroit retirees and workers approve bankruptcy plan, agree to pension cuts,” MLive, July 22, 2014.

- Nathan Bomey, John Gallagher, and Mark Stryker, “How Detroit Was Reborn: The Inside Story of Detroit’s Historic Bankruptcy Case,” Detroit Free Press, accessed November 5, 2015.

- Sam Roberts, “Infamous ‘Drop Dead’ Was Never Said by Ford,” New York Times, December 28, 2006.

- Ada Carr, “Contaminants Found in Flint, Michigan, Drinking Water; City to Reconnect to Detroit Water Supply,” Weather.com, October 9, 2015.

- Source declined to be identified for this article.

- Tonya Allen et al., “Don’t Forget the Motor City: Philanthropy in Detroit” (transcript of panel discussion, Bradley Center for Philanthropy & Civic Renewal at the Hudson Institute, November 6, 2013), 5.

- Ibid., 7.

- This and all other quotes related to Tonya Allen are from an interview with the author, October 16, 2015, unless otherwise noted.

- Allen, “Don’t Forget the Motor City,” 18.

- This and all other quotes related to Emmett Carson are from an interview with the author, July 28, 2015, unless otherwise noted.

- Nathan Bomey, “Pensions, debt obstruct Snyder’s Detroit schools plan,” Detroit Free Press, June 22, 2015. The report of the Coalition for the Future of Detroit Schoolchildren notes that the schools spend $1,120 per pupil on debt service for working capital, not to mention the additional $3,586 per pupil that the district owes in capital debt. See The Choice Is Ours: Road to excellence for troubled Michigan schools begins in Detroit (Detroit, MI: Coalition for the Future of Detroit Schoolchildren, 2015), 19, 20.

- “Darnell Earley named new emergency manager as community discusses future of city’s public education,” Detroitk12.org, January 13, 2015.

- Source declined to be identified for this article.

- Rick Cohen, “The Next Foundation Challenge in Detroit: A Bankrupt Public Education System,” Nonprofit Quarterly, March 30, 2015.

- Coalition for the Future of Detroit Schoolchildren, The Choice Is Ours, 10.

- “The Plan for Detroit Schools,” Reinvention Blog, accessed November 5, 2014.

- This and all other quotes related to Steve Tobocman are from an interview with the author, October 13, 2015, unless otherwise noted.

- This and all other quotes related to Laura Trudeau are from an interview with the author, October 13, 2015, unless otherwise noted.

- Frank Hammer, “A Bloodless Coup d’état in Detroit,” interview by Sharmini Peries, The Real News Network, February 9, 2015, transcript; and Matt Helms, “Snyder appoints review commission for Detroit,” Detroit Free Press, November 10, 2014.

- Daniel Howes, Robert Snell, and David Shepardson, “Donors pitched to aid DIA, pensions: Mediator floats having foundations step up so Chap. 9 stays on course,” Detroit News, November 14, 2013, accessed November 18, 2013, link no longer accessible.

- Daniel Howes, “Way out of Chapter 9 is hardest challenge,” November 15, 2013, accessed November 18, 2013, link no longer accessible.

- Steven Church and Sherri Toub, “Detroit Judge’s Expert Says Voters Pose Recovery Risk,” Bloomberg Business, November 8, 2014.

- Mark Stryker, “DIA pay hikes raise eyebrows, anger politicians,” Detroit Free Press, October 9, 2014.

- Laura Berman, “Van Gogh for sale? DIA tiptoes into art auction market,” Detroit News, May 15, 2015.

- Niraj Warikoo, “Detroit activists say city’s poverty is being ignored,” Detroit Free Press, October 19, 2015.

- This and all other quotes related to Sarida Scott are from an interview with the author, October 15, 2015, unless otherwise noted.

- john a. powell, “john a. powell: Regionalism and Race,” Reimagine!/Race, Poverty and the Environment.

- Ibid.

- Elizabeth Myrick, The Kresge Foundation: Will This Bold Grantmaker Become the Next Great Social Justice Foundation? (Washington, DC: National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy, 2015), 8.

- This and all other quotes related to Rip Rapson are from an interview with the author, October 12, 2015, unless otherwise noted.

- “Livernois Avenue of Fashion,” Avenue of Fashion, accessed December 15, 2015.

- Motor City Match, accessed October 14, 2015.