January 7, 2016; USA Today

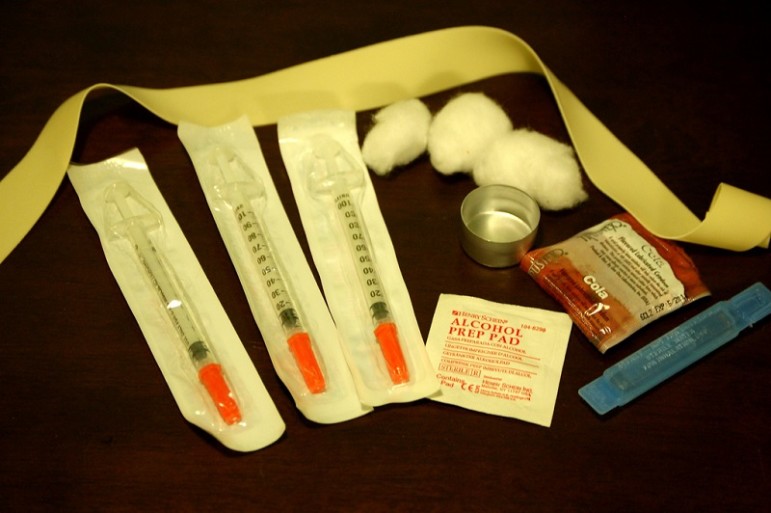

USA Today reports that included in December’s spending package signed into action by President Obama was a federal prevision removing the ban on federal funding for needle exchange programs. Syringe exchange programs allow IV drug users to have access to clean needles, helping prevent the spread of infectious diseases such as HIV/AIDS and Hepatitis C. The first federal ban on funding for syringe exchange programs was enacted in 1988. The ban was lifted in 2009 and reinstated in 2011—despite overwhelming scientific evidence supporting needle-exchanges as an effective method for preventing the spread of disease.

The current law does not allow for funds to be used for the actual syringes. Instead, it offers funding for overhead costs and personnel, which can guide users into treatment programs. In the coming year, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention will identify at-risk areas in the U.S. that will receive allocated funds.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Lifting the ban on federal funding for needle-exchange programs comes on the heels of one of the largest HIV outbreaks in the U.S. Beginning in early February 2015, southeastern Indiana was shaken by the spread of HIV within its IV drug user population. By the end of 2015, new incidences totaled 184 with an estimated cost of treatment totaling more than $100 million. An average needle exchange program operates on a yearly budget of $100,000 to $300,000. The prevention rate for exchange programs can reach upwards of 80 percent, making needle exchange programs both cost saving and effective.

While Kentucky Republicans introduced the spending measure, there will be real and legitimate fears within the harm reduction community of short-lived access to federal funding. Will new funding bring a wave of needle-exchange programs, providing education, access, and prevention only to be shut down with the forthcoming change in political office?

Harm reduction advocates are right to worry; it is likely that rural America will be left out. Access to healthcare in rural America is challenging at best. While the CDC will actively identify pockets of infectious diseases linked to IV drug use, they will be more than likely be centered on urban areas, and the funding will follow. The National Rural Health Association estimates only 10 percent of doctors practice in rural America, where a quarter of the U.S. population lives. Mobile clinics equipped with trained staff and rapid testing kits will be essential in reaching a vulnerable population.

Preventing outbreaks like those in Indiana and Kentucky means harm reduction programs need to be implemented before rates skyrocket and before an infection spreads through highly susceptible communities—not as an aftereffect of devastating consequences, but as an evidence-based prevention and harm reduction method.—Stacey Burton-Alcocer