Nonprofits on the Edge: An Introduction to This Series

This is one of three case studies submitted as part of the graduate course “Nonprofit Governance and Management,” taught by Dr. Chao Guo, associate professor and Penn Fellow in the School of Social Policy and Practice at the University of Pennsylvania. The cases represent three different organizations that have come back from the brink of dissolution. Each did it in a different way, and none of them necessarily has an easy road ahead.

With each of these organizations, one could use multiple lenses to analyze what caused them to decline—and it is almost always a combination of factors that impose frailty over time—but in the stories of the comebacks, the levers were clearer. The generators of organizational frailty, however, can outlast an immediate save—hanging around like unwanted spirits waiting to reassert themselves.

In our editors’ commentary on these cases—in this case, found at the end of the article—we have tried to discuss what some of these persistent issues may be. It is important to remember that the symptoms of organizational problems often lie very distant from the problem generator, which may be the organizational culture and belief systems, or the organization’s birth story. In some cases, additionally, the form does not fit the function in the right way, and the function just spits it out.

Understanding organizational dynamics makes for better leadership, and the more curiosity you have about why an organization seems to be in decline, the better. Too many boards and leaders look for the most immediate relief at hand, and this stops a process of inquiry that in the end could create far more enduring strength over time.

Network as the Form: Reconfiguring Architecture for Humanity

This article is from the Nonprofit Quarterly’s winter 2015 edition, “When the Show Must Go On: Nonprofits & Adversity.”

From 1999 to 2014, Architecture for Humanity (AFH) worked in over forty-four countries, built more than two thousand structures, served over two million people, and established nearly sixty chapters of design professionals around the world.1 Amid this success, AFH’s U.S. headquarters filed for Chapter 7 bankruptcy in January 2015. This case study looks at the origins of, and factors that led to, the “death” of the best-known humanitarian architecture organization in the world. However, it will also reveal that AFH is regenerating via its worldwide network of chapters, which it had begun developing around 2004, and which gathered more formally under the name Architecture for Humanity Chapter Network upon AFH’s closure.2

Origins

In the summer of 1999, Cameron Sinclair, architect and writer, and Kate Stohr, digital media producer, observed a need to aid the refugees returning to war-torn Kosovo, following the withdrawal of Slobodan Milosevic’s Serbian forces brought on by NATO’s political pressure and bombing campaign. Refugees were returning to ruins without adequate housing; AFH was conceived with the goal of providing design solutions to the devastated population. The solutions implemented by AFH came from an open design contest that led to the erection of shelters for the refugees. The success of the Kosovo project led to more projects for AFH, both in the United States and abroad.3

From its modest beginning in Sinclair and Stohr’s three-hundred-square-foot New York apartment, AFH grew by 2011 into a business of thirty-six paid employees and numerous volunteers located in downtown San Francisco.4 Its growth as an organization was not limited to its San Francisco office but also included a confederation of chapters based on an “open-source model of business.”5 At the organization’s peak, AFH had over sixty of these chapters—each a volunteer branch office that consisted of dues-paying members, with at least one architect in the mix.

The chapters were independently registered charities that relied upon the corporate entity of AFH for institutional support, which included branding, access to a bank account, online/web support, general liability insurance, and the name recognition of being associated with Architecture for Humanity.6 Although AFH provided support, the chapters functioned as autonomous entities, without much communication between headquarters and fellow chapters.7 AFH had developed the chapters as a way to maintain the organization’s capacity to manage projects around the globe. The chapters were established to identify local problems and design local solutions, as the organization aimed to provide a combination of grassroots-inspired, socially responsible design that used local expertise to realize projects. Membership and chapter growth flourished in the years before AFH filed for bankruptcy—so much so that in 2011 Sinclair stated that AFH had “built an army” of volunteers and professional designers.8

As time progressed, AFH expanded its vision beyond design/build ventures, committing to projects that would function as job stimulation packages for the at-risk communities it served. The organization would send designers to work alongside residents in what AFH considered to be long-term investments of four to five years—compared to the earlier design/build projects of just a few years each. AFH’s efforts in Haiti after the severe 2010 earthquake followed this new vision; in March of that year, AFH headquarters established a field office in the Haitian capital, Port-au-Prince. With this new office, AFH “not only provided architectural services themselves, they also helped to corral the talents of Haitian architects and builders, as well as training and employing hundreds of Haitians to carry out their projects.”9 AFH’s inventiveness in Haiti led to the completion of numerous construction projects between 2010 and 2015 that positively impacted the lives of over a million Haitians.10

Because AFH was expanding the vision and scope of its work, this caused a strain on its finances. Fundraising was not keeping up with the needs of the organization, which would be the cause of its downfall.

Leadership Change and Financial Challenges

In the midst of success in Haiti, the AFH cofounders Sinclair (also executive director) and Stohr (also advisor to the board of directors) decided to leave the organization. According to a press release published by Archinect, Stohr and Sinclair were leaving to “explore new ventures.”11 The release went on to state that Stohr planned to resume her career in media production.12 Sinclair further explained why he left the organization in an interview with Dezeen: “I was trained to be an architect, but I was never expected to be an architect—I was just managing people. […] It became less fun and for me creatively it was not fulfilling at all.”13

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Before their departures, in 2013, they worked alongside the board to craft a five-year strategic plan.14 AFH’s leadership articulated the vision that “within five years Architecture for Humanity will plan, design, and build beautiful, sustainable spaces [that] both shelter and inspire—and in doing so, […would] collectively improve the lives of one million people.”15 The vision was aligned with the organization’s mission: “Building a more sustainable future using the power of design through a global network of building professionals Architecture for Humanity brings planning, design and construction services to communities in need.”16

Five strategic priorities were enumerated in the plan by AFH leadership as the next steps to bringing the five-year plan to fruition:

- Ensure design excellence. Because good design builds community equity.

- Establish lasting community presence. So that we can deepen our impact while continuing to work locally.

- Grow general fundraising. In order to in crease strategic flexibility and decrease risk.

- Measure and communicate our impact. So that we may position the organization to better attract capital partners and talent.

- Offer expanded community development services. So that we may better meet the needs of the underserved communities and create more opportunities for great design.17

The priorities demonstrated the desire for AFH to pursue excellent design and community impact into the foreseeable future; but they also illustrated some of the organization’s weaknesses, such as the inadequate fundraising for general operations and the lack of communication between chapters.

The responsibility of fulfilling the vision outlined in the strategic plan went to Eric Cesal, the executive director appointed by the AFH board to succeed Sinclair. Cesal supported the mission and vision of AFH, as he saw providing assistance to troubled communities, education to at-risk communities, and training and mentorship to empower designers to change the world as key tenets of the organization.18 Unfortunately, AFH would file for bankruptcy before the conclusion of Cesal’s first year at the helm. According to an interview with Architectural Record, Cesal stated that he had entered into the directorship of an organization that was $2.1 million in debt. He observed that the organization had been borrowing from its “restricted program dollars to fund unrestricted projects.”19 This internal borrowing created a debt that Cesal and the board saw as insurmountable.

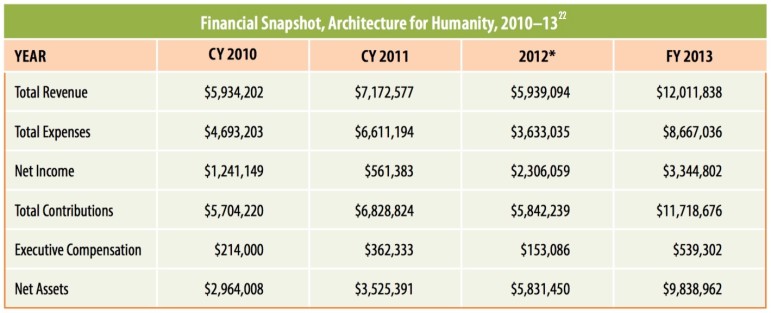

According to AFH’s filings with the IRS, between 2008 and 2013 administrative expenses grew almost fivefold—from $210,888 to $1,080,422. And, over the same timespan, fundraising expenses increased more than tenfold—from $57,492 in 2008 to more than $592,000 in 2013.20 These increases were aimed at supporting the demands of an expanding international outreach. Additionally, given the organization’s successes in Kosovo, Haiti, Japan, and Rwanda, its desire to respond to natural disasters—events that do not allow for long-term financial planning—likely pressured budgets. Clearly, the founders’ passion was for maximizing social impact. However, when analyzing AFH’s growth over its inaugural decade, it is crucial to consider how broadening outreach to global networks—a mission that combined design and socioeconomic factors and a seemingly unending queue of constituents requesting assistance—impacted the financial health of the organization. Only about 30 percent of projects proposed to AFH could be accepted due to high demand and limited resources.21

The table above shows the growth of AFH’s net assets year-over-year from 2010 through 2013. This data, however, does not detail the internal financial issues that developed and ultimately led to the organization’s bankruptcy and closure. AFH’s financials do not overtly reveal the glaring $2.1 million deficit identified by Cesal, as the overall cash flow hid what appeared to be internal borrowing that hamstrung the organization. Cesal and Sinclair both hinted in separate 2015 interviews that the deficits were the result of unchecked growth that stretched or exhausted resources, leading to this internal borrowing from designated funds. Although Sinclair stated that there hadn’t been a deficit during the first fourteen years of AFH, Cesal identified the presence of financial issues as early as 2011, and noted that the debt grew exponentially over 2012 and 2013.23 Arguably, this debt was the catalyst for the strategic priority of general fundraising identified in the five-year plan.

Reincarnation

The closure of AFH headquarters in January 2015 led to a flurry of e-mails, tweets, phone calls, and digital meetings between chapters caught completely off guard by the sudden action in San Francisco. The chapters interested in continuing the work of AFH organized an “independent congress” in early February 2015, led by Rachel Starboinsky, managing director of the New York chapter, and Garrett Jacobs, a former codirector of projects at AFH headquarters.24 Out of this congress, a quasi-grassroots collaborative, Architecture for Humanity Chapter Network (“Chapter Network”), was organized, with Jacobs serving as acting chair. In an e-mail to Laura Raskin, writing for Architectural Record, Jacobs wrote that Chapter Network was establishing “a transitional steering committee with representatives from every region of the network.”25

This collaborative determined that a more diverse approach to bringing “needs based, participatory design” to communities in need was essential. Identifying the desire to move beyond architecture and increase inclusivity in order to encourage business incubation through “collectively mobilized, collaboratively led” partnerships, Chapter Network articulated its early vision for continuing humanitarian design.26 It should be noted that this approach is not a far cry from Sinclair’s vision for humanitarian design highlighted in his 2011 TEDxVienna talk.27

Alicia Breck, transition coordinator, was hired in June 2015 with funds from a Curry Stone Foundation grant, to shepherd the new organization through its rebirth.28 According to Breck, the similarities between AFH and the reorganized Chapter Network are numerous, with the most significant difference being a focus on domestic projects instead of international ones.29 Although the international projects put AFH in the spotlight, the toll those projects took on the organization over the last five years cost it its existence.30 Chapter Network is still in the planning stage, and Breck indicated that the leadership recognizes that the new mission has to look at “how design impacts people,” while placing the organization within the international “public impact design movement.”31

Collaboration, transparency, and the provision of open-source information are driving the transition process. This activity is aimed at chapters learning from each other with common project experiences and related challenges across the globe, a technique that was uncommon in the previous relationships between AFH headquarters and chapters. This collaborative effort is further enhanced by a steering committee that considers what aspects of the AFH mission to continue while also establishing structures for long-term governance.32

Breck sees the reincarnated AFH as an organization geared for cross-sector collaboration. Multidisciplinary impact requires a greater diversity of leadership growing out of architecture and other areas, including community development, economics, and urban planning. The new organization is in the process of renaming and rebranding as it transitions from AFH’s independent chapters to a more collaborative alliance.33 Chapter Network’s new mission statement, “Foster local grassroots design coalitions to serve communities in need,” defines its direction as a nonprofit focused on impactful design and community development for the public good.34 In an interview for this article, Breck discussed diversifying revenue streams (grants, crowdsourcing, and matched donations) and breaking from relying primarily on project-specific funding (which AFH had been doing before the bankruptcy), in order to meet Chapter Network’s financial needs. She also identified the need for accountability regarding the organization’s overhead costs.

The movement of Chapter Network from the past toward the future is best summed up by Jacobs, in an April 2015 interview with Design Build Network: “I am very proud of the resiliency of the chapters to continue on with virtually no support from the headquarters […] I am also exceedingly impressed with the chapter leaders’ ability to agree on the best path forward. Over the past ten years the chapters have been virtually autonomous, without much contact with one another; now with exuberant energy we are gathering and coming to consensus without much hesitation.”35

Commentary: In the changeover from the industrial era to the knowledge era, networks have become an increasingly favored form of organization—they can spread an approach and learning quickly among communities of practitioners. In the case of Architecture for Humanity, an attractive idea brought people into conversation and common cause globally—and, when the original “hub” of the hub-and-spoke activity began to fail, the network quickly changed to a multihub system that is less frail but will require careful knitting. As Valdis Krebs describes in “Building Adaptive Communities through Network Weaving,” Now that other hubs are emerging in the network, the various weavers begin to connect to each other, creating a multi-hub community. Not only is this topology less fragile, it is also the best design to minimize the average path length throughout the network—remember, the shorter the hops, the better for work flow, information exchange, and knowledge sharing! Information percolates most quickly through a network where the best-connected hubs are all connected to each other. A network with many hubs is also very resilient and cannot be easily dismantled.” But, Krebs cautions, turf or political issues are a real threat to this phase of network development.

Notes

- Megan Jett, “Infographic: Architecture for Humanity,” ArchDaily, June 12, 2012; and John King, “Architecture for Humanity shut; nonprofit helped disaster victims,” San Francisco Chronicle, January 17, 2015.

- Architecture for Humanity, ed., Design Like You Give a Damn [2]: Building Change from the Ground Up (New York: Abrams, 2012), 46.

- WGBH Educational Foundation, “A Kosovo Chronology,” Frontline, accessed October 9, 2015; and Jett, “Infographic.”

- Kriston Capps, “Can Architecture Save Humanity,” Architect, September 8, 2011.

- Cameron Sinclair, “My wish: A call for open-source architecture,” TED Prize talk, February 2006.

- Shaunacy Ferro, “What’s Next For Architecture For Humanity? Where The Architecture Nonprofit Went Wrong, And Where Volunteers Hope To Take It Now,” Fast Company, January 22, 2015.

- Chris Lo, “Architecture for Humanity: A new chapter,” Design Build Network, April 27, 2015.

- Cameron Sinclair, “Architecture for Humanity (Evolution, Not Revolution),” TEDxVienna talk, November 12, 2011.

- Rory Stott, “Architecture for Humanity Announces Completion of Haiti Initiatives,” ArchDaily, November 9, 2014.

- Ibid.

- “Cameron Sinclair and Kate Stohr, co-founders of Architecture for Humanity, to step down and help form a five-year strategic vision,” Archinect News, September 9, 2013.

- Ibid.

- Dan Howarth, “‘When I said architects should get involved in humanitarian issues, people laughed at me,’” Dezeen, August 27, 2015.

- Cameron Sinclair, “New Strategic Plan Announced: Co-Founders to Transition and Launch Founders Fund,” September 4, 2013, architectureforhumanity.org, accessed via web.archive.org.

- Architecture for Humanity, 5 Year Strategic Plan: Year 15 to 20—Moving from Organization to Institution, September 4, 2013.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Vanessa Quirk, “Architecture for Humanity Turns Fifteen, Names New Executive Director,” ArchDaily, June 10, 2014.

- Laura Raskin, “Architecture for Humanity Closes, But Chapters Go On,” Architectural Record, February 12, 2015.

- “Money Woes Close Architecture for Humanity,” Chronicle of Philanthropy, January 20, 2015; and data retrieved from “Form 990: Return of Organization Exempt from Income Tax,” CY 2008, Architecture for Humanity, Inc., September 8, 2009, org.

- Ferro, “What’s Next For Architecture For Humanity?”

- Data retrieved from “Form 990: Return of Organization Exempt from Income Tax,” FY 2011, 2012, 2013, Architecture for Humanity, Inc., accessed October 12, 2015, charitynavigator.org; and data retrieved from “Form 990: Return of Organization Exempt from Income Tax,” CY 2010, Architecture for Humanity, Inc., accessed November 10, 2015, 990s.foundationcenter.org.

- Ibid.; and Ruth McCambridge, “Architecture for Humanity Closes Soon after Founders Leave,” Nonprofit Quarterly, January 20, 2015.

- Raskin, “Architecture for Humanity Closes, But Chapters Go On”; and Lo, “Architecture for Humanity.”

- Ibid.

- “Why We’re Rebranding,” afhnetwork (blog), August 8, 2015.

- Sinclair, “Architecture for Humanity (Evolution, Not Revolution).”

- Lo, “Architecture for Humanity.”

- Alicia Breck, in an interview with the authors, October 15, 2015.

- McCambridge, “Architecture for Humanity Closes Soon after Founders Leave.”

- Breck, interview.

- Ibid.

- Sabrina Santos, “Help Shape Architecture for Humanity’s Rebranding,” ArchDaily, September 7, 2015.

- As phrased by Alicia Breck, in e-mail correspondence with the authors, October 27, 2015.

- Lo, “Architecture for Humanity.”