January 20, 2016; Christian Science Monitor

NPQ couldn’t be more tired of hearing how nonprofits should be run like businesses, a statement that is still brightly aped as revelatory even decades after it was first introduced. But yesterday, the Christian Science Monitor took on the limitations of such views when applied inappropriately to government—in particular, in the case of the poisoning of 8,500 children in Flint, Michigan via its low-cost water system. A Flint Journal Freedom of Information Act request recently surfaced information suggesting that an outbreak of Legionnaire’s disease that killed 10 people was also connected to the befouled water.

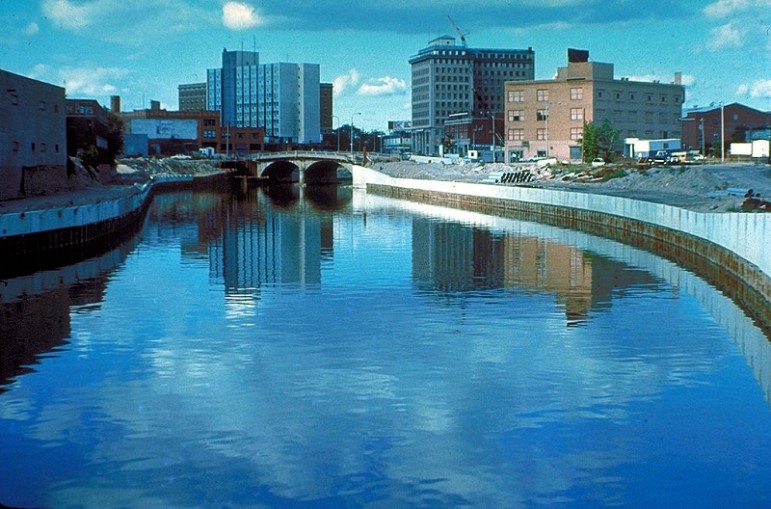

In 2014, as it prepared for a more permanent transition, Flint started to pump its water from the Flint River, which caused lead to leach out of older household pipes in this largely low-income community. What does this have to do with being businesslike? Michigan’s governor, Rick Snyder, openly prides himself on his pragmatic approach, promising to pull Michigan out from its financial tailspin through the use of business practices. But, according to Thad Kousser, a political science professor at the University of California in San Diego, this particular crisis epitomizes the limitations of an entrepreneurial method of governance.

“What this crisis points out is one of the limits in running a government as a business,” says Professor Kousser, commenting that the problem stemmed from what appears to have been a tradeoff between cost-cutting measures and public health.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

“The private marketplace works because of competition, but governments often have monopoly,” he notes. “When Volkswagen screws up, you can buy a Ford. But when lead starts coming out of your tap, you can’t just turn on another tap.

Last week, President Obama issued a federal emergency declaration, pledging $5 million to help the city. This week, he said he is appointing a water czar. Snyder has requested $28.5 million, which will cover only the most immediate needs in Flint; these expenditures are only a peek at the actual long-term costs, and only in financial terms.

Some fault the disconnected hierarchical approach – sans community engagement – to governance that the state imposes on municipalities in financial trouble, as Flint was when the fateful decisions about the water system were made by emergency manager Darnell Earley. Earley is now in charge of reforms to the Detroit School system, which teachers abandoned in a mass sick-out on Wednesday meant to highlight the state of some of the system’s buildings, which include more hazards to children in the form of buckling floors, mold, mildew, and— in some classrooms—a lack of heat. Matt Grossmann, director of the Institute for Public Policy and Social Research, says, “The decisions were made at times when Flint was being managed by [state-appointed] emergency managers. A review of that policy and its implementation here is warranted.”

Of special concern in Flint and now in Detroit is the disregard for the engagement of local residents. That is the bottom line of this situation: the protection of the youngest of the state’s residents from state-sponsored or encouraged health hazards that could very well ruin the rest of their lives and run up long-term costs for us all.—Ruth McCambridge