Please head here to read the first part of this series, “On Full Philanthropic Engagement.” All set? Great!

Opening the Terrarium: How a Change in Operating Model Can Expand Effectiveness and Impact

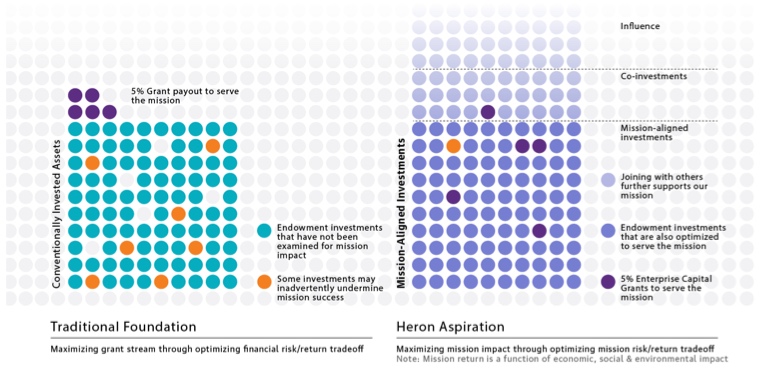

When we set out on Heron’s current journey, we did so with the idea of building incentives into our own operating model that would propel us outside our terrarium—to become not only open to but forcibly engaged with the entire economy. As noted above, we realized that the strict segregation of “giving grants” (program side) and “extracting maximum profits” (investment side) as embodied in most foundations is mirrored in society: poverty is made more searing by economic segregation and the isolation of poor people and of antipoverty work from the economy as a whole. Modeling and replicating that separation within the business model of the foundation might actually be undermining our goals. In Gandhi’s words, a better path was to “be the change” to which we aspired. And we thought that approach should be applied more generally to foundation philanthropy.

With that in mind, we set about to build and test a foundation that might better suit the challenges and opportunities of the 21st century. We asked ourselves, “What kind of operating model might we build if we focus all of our resources on achieving our mission, assuming that we will continue to operate under the regulatory rubric of the private foundation?”

Our first step was to merge our program side and the investing side into a single unit that deploys all the foundation’s capital (financial, social, reputational, intellectual, and moral, etc.) in pursuit of our mission. In this way, we positioned the foundation (along with the rest of the nonprofit sector) as a distinctive part of, rather than as distinct from, the larger economy. Our success is thus defined and measured by the mission and financial success of all of our investees, whether nonprofits or for-profits, beyond our walls. We no longer separate grant-making from investing as if they exist in two different worlds. We aspire to monitor the financial and mission activity of the holdings of the foundation as a whole rather than as two disconnected parts.

As noted above, we believe that this approach is, simply, philanthropy. Philanthropy is, first and foremost, an orientation to life, available to and potentially shared by all, every day; and second, a distinctive part of commerce with a specific role in it, not a special class of operating entities protected from it. As Jim Collins put it in Good to Great and the Social Sectors,1 “The critical distinction is not between business and social, but between great and good.” Heron seeks a portfolio of great organizations that will deliver over time.

Our transition has involved philosophical and culture changes, alongside process and personnel changes. One guiding principle of that transition is our view that “all investing is impact investing, and all enterprises are, essentially, social.” That view comes with these corollaries: that the impact of all our investees and investments may be positive, negative, or even neutral; and that the enterprises we invest in could be intentionally or unintentionally socially positive or negative based on their “net contribution” to the world, and that social performance, broadly construed, varies over time in the same way as financial performance does. In a very real sense, all foundations are already doing “impact investing.” They just don’t know if their impact is positive or negative.

At Heron, we have been on a journey of change for the last three years, and we’re not yet done. We have transformed ourselves from a Docket Model foundation (with the traditional bright line between investing and grant making, notwithstanding a strong track record in impact investing) into a more streamlined and market-facing “Pipeline” model, that tries to tailor capital investment to meet the needs of enterprises, takes a specific financial role (growth capital investor) and injects opportunism into our process. We are now in the early days of building our ultimate “Platform” model, which we anticipate will open our terrarium even wider by looking to broaden our reach and that of our allies both within and outside our sector. Given that foundation endowments comprise less than one percent of assets under management, we must invest to influence others if we are to achieve our goals.

As we continue to evolve, some operating imperatives have already emerged. The most universal principle, exemplified by removing the mission and finance divide, is that integrating mission and finance creates the best possible menu of outcomes.

An integrated investment policy: mission & finance together

If “all enterprises are social enterprises,” and “all investing is impact investing,” our governing documents and operating structure must reflect this reality. Our 2014 Investment Policy Statement notes:

“All enterprises, regardless of tax status, produce both social and financial results, on a spectrum from positive to negative, including ‘neutral.’ Their financial and social performance is measureable and varies over time. The conscientious investor takes note of both.”

Even if the IRS has divided the world into “charitable” and “non-charitable” assets, these distinctions are an artificial construct created for tax compliance, not a reflection of the realities of our missions or markets. The distinction is relevant and important for good legal compliance, but it is in no way a business model requirement or a strategic imperative. Our corporate governance documents reflect this policy, including full compliance with a philanthropic institution’s fiduciary duties of loyalty, care, and obedience to mission, which apply to the deployment of all our assets, including grants.

A single philanthropic staff

With one unifying investment thesis, and a market that includes all kinds of enterprises and asset types, it’s confusing to maintain two segregated staffs with separate missions, skill sets, and worldviews. Heron eliminated the distinction, and now has one staff dedicated to deploying the foundation’s assets for mission. While each member of our team arrives with a different level of expertise in finance and investing across asset classes (and including grants), all are expected to move up the learning curve. Though colleagues have asked good questions about the availability of talent, we have not to date had a problem attracting good people. Generally, specific skill sets are less important than judgment and temperament: comfort with experimentation, uncertainty, change and, most importantly, operating in an environment that welcomes the challenge of persuasion and influence outside the foundation—with no direct control over outcomes.

Knowledge of what we own: Full examination of all our holdings at the enterprise level

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

As a philanthropic institution, we have a fiduciary duty of obedience to mission, and that requires that we track impact of all our assets on society, and make decisions in light of that knowledge. All holdings perform both positively and negatively on social as well as financial dimensions. Performance variation applies to all kinds of enterprises. Nonprofits aren’t always “good” and for-profits “bad”: both have an impact on the value foundations are meant to foster, and their performance varies over time. While our accounting ambitions now outstrip the scope of available data, we have examined all our investments to discover at a high level their base performance, financial and “social.”

A challenge in fully examining our holdings for mission was to gain visibility into the enterprise view, that is, to see through the “top-down” asset classes to the underlying enterprises that give those assets value. These enterprises are the level at which “impact” occurs and foundations can foster value, both financial and social. At the end of the day, we’re looking for greatness.

The ability to measure, with integrity, positive and negative financial and social performance across enterprises and asset classes over time

We recognize that knowing what we own is a first step. Given that all assets are mission assets and can perform on both financial and social dimensions positively or negatively, we must track our market performance accordingly, across all legal forms of business (nonprofits, for-profits, cooperatives, partnerships, public companies, governments, and more) and benchmark them against peers, outside our own walls. While management intent is important, it is not determinative; and while due diligence can be helpful, it measures only a single segment of time. Our operating response has been to fully examine all holdings in our portfolio (as noted above), and to contribute to the development of the infrastructure needed to track and benchmark all our holdings in real time. For our direct investments, we do not keep any special reports inside the foundation, but instead we direct reporting to an outside data warehouse called CoMetrics. For our indirect investments, we partner with managers capable of providing financial and social performance data, and look to developed data capacity from providers such as Bloomberg, MSCI, and similar.

Collaborative, cooperative, outward-looking routines

Given a much-too-large pipeline of deals (all capital across all asset classes) with a range of projected financial and social returns and liquidity characteristics, we cannot be blind to the importance of the wide world of co-investors and fellow customers to achieve our goals. We have a powerful incentive to share underwriting and follow trusted partners into deals. Collaboration, syndication, and the use of funds and managers are not merely desirable for program reasons but mandatory for financial reasons given a relatively small operation. We therefore are developing, with others, data infrastructure, comparable performance analyses, certification protocols, investment vehicles, standard documentation, cross-mission financial vehicles, and the like, to stimulate and enable influence and co-investment and reduce transaction costs. Some specific projects include:

Common data standards and cohorts

If Heron (or any foundation) requires specialized data reported to it alone, it creates an expensive world apart for its own purposes (with the costs borne mainly by its grantees and investees). I am not aware of any foundation that requires specialized reporting from its conventional investment holdings—hedge funds or for-profit corporations, for example. The investment side of foundations depends on standard reports on investment positions, and can find data to compare its performance, and that of its managers to peers. We aspire to extend that capacity to all of our holdings, including grants. We avoid distinctive forms of measurement, customized data or keeping specialized internal databases of financial or social metrics on our direct investments (typically nonprofits, small for-profits, and cooperatives). Instead we are working with sources that provide current, comparable data on financial and, where possible, social performance across asset classes, and look to make the social finance market simpler and more standardized.

Extensive standardized financial data are available from publicly listed companies, but environmental, social and governance data (known as ESG) are neither consistently reported nor standardized. With an enterprise capital grant to the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB), we are participating in an effort to build that capacity into the DNA of public and private company reporting, connecting for-profits to social performance consistently and comparably. While ratings and analysts’ reports encompassing ESG data will become key to investment decisions, it is paramount that the basis on which those reports are developed, like the basic elements of financial reports, rely on consistently reported data, in exactly the same way as is required by the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB). With an equity investment in CoMetrics, we are working to build the same kind of comparability—financial and social performance data—for nonprofits and privately held businesses as well. We acknowledge that this will take time and money.

A transition from a “docket” culture (inwardly driven) to a platform/network culture (responsive to external opportunities and conditions)

Our operations and operating routines are continuing to evolve. We are looking for ways to not only carry out business in two-party transactions (where we expect social and financial return from enterprises), but with groups of affiliated customers, investors and enterprises who seek success systemically.

In addition to working on developing the internal and external infrastructure to extend this style of investing beyond Heron and beyond philanthropy, we are developing knowledge and communications as a strategic imperative, bringing financial and non-financial impact to bear—with the goal that an economy that expands the number and contentment of its participants becomes standard.

Looking Forward

One of the distinctive duties of social sector nonprofits is to push to the margins—that is, to work toward a world where we are no longer needed, exiting businesses where the mainstream economy is working well and where problems are episodic (and readily treated by charities), not endemic. Especially in areas such as health, anti-poverty, environment and social justice, our goal is to make ourselves superfluous.

For Heron, that means looking forward to the day when our goal of helping people and communities help themselves out of poverty is met. That would be the day when the current market failures end and the mainstream economy reliably provides jobs, livelihood and opportunity; when poverty is rare and marginal rather than growing and structural; and when philanthropic resources are directed toward market failures that exist where economic value is unknown and unknowable: basic research in science, the arts, spirituality and similar—while “return” tends to be outsized and widely shared.

For us, this means a focus on making the market and the economy work for and include all of us. Given Heron’s core business of investing, it means deploying all assets to achieve our mission, so the mainstream economy works for more and more people. Today and in the future, we will be constantly working to improve the standard of investing more broadly, and all along the way, to assure quality and integrity in our portfolio. Beyond that, and the ultimate test of the platform business model, will be our ability to recruit (and join with) as many additional aligned investors (including donors and investors of non-financial capital) as is possible. To fulfill our fiduciary duty of obedience to mission and public purpose, we are working toward the day when the investors who are deemed to be out of step with the market and society are those who fail to examine, vet, and optimize their investments for social as well as financial results.

Notes

- Collins, Jim. Good to Great and the Social Sectors: Why business thinking is not the answer: a monograph to accompany Good to Great. Boulder, Colorado: Harper Collins, 2005.

Appendix A: How we are Evolving, Docket to Pipeline to Platform/Network

Model |

Docket > Modified Docket |

Pipeline > Modified Pipeline |

Pipeline > Network |

| Investment Thesis |

|

|

|

| Time Horizon |

|

|

|

| Leading Question(s) |

|

|

|

| Transparency |

|

|

|

| Key Systems & Routines |

|

|

|

| Transaction Size |

|

|

|

| Staff Structure |

|

|

|

| Staff Skills |

|

|

|

| Reporting & Data |

|

|

|

| Planning Model |

|

|

|

| Market |

|

|

|

| Communication and influence |

|

|

|