July 10, 2016; New York Times and Salon

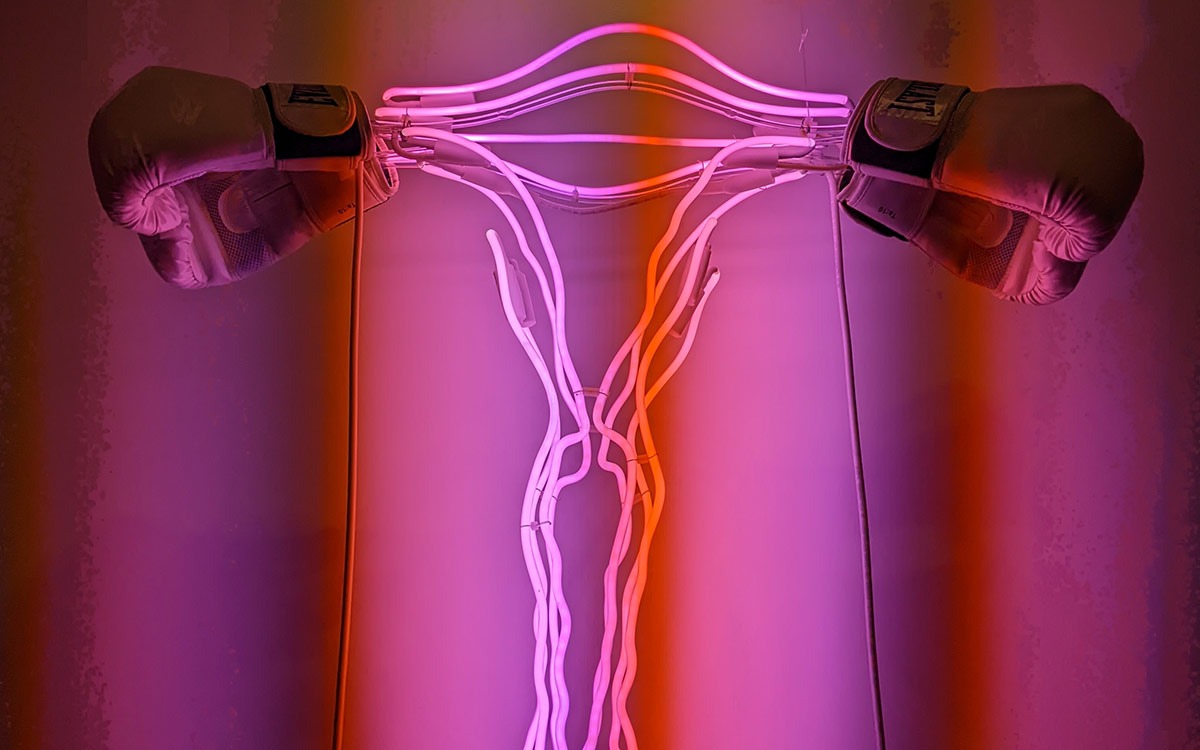

Those who thought the Supreme Court’s ruling striking down Texas’s use of its power to oversee medical practice within its borders as having gone too far because it created an “undue burden” on women ended the battle over women’s right to access the full array of reproductive medical care were wrong. Opponents of abortion see the ruling as a challenge to reframe the issue. By attacking the right to choose from a different angle, they still hope to impose their view on all women.

When the Supreme Court gave states the right to regulate access to abortions in a 1992 ruling modifying Roe v. Wade (Planned Parenthood v. Casey), abortion opponents quickly and effectively shifted their efforts from Washington, D.C. to the fifty state capitals. Hundreds of new laws passed, establishing regulations designed, they said, to protect a women’s health. Since 2011, on average 52 new state laws have been enacted annually. Brick by brick, a higher and higher wall was built that made it increasingly more difficult for a woman to find a clinic prepared to serve them.

The Supreme Court now prohibits states from establishing requirements that place undue burdens upon women to receive the care they need and that state standards must be widely seen as medically necessary by experts. Justice Stephen Breyer stated in his majority opinion that the Texas law did not offer “medical benefits sufficient to justify the burdens upon access that each imposes. Each places a substantial obstacle in the path of women seeking a pre-viability abortion, each constitutes an undue burden on abortion access, and each violates the Federal Constitution.”

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

If focusing on women’s health is too difficult, opponents of abortion now seek to prioritize their efforts on the fetus. Mary Spaulding Balch, the director of state legislation for National Right to Life, sees “The Supreme Court case as focused on the health of the mother, but we take a different approach. Our legislation focuses on the humanity of the unborn child.” Starting from the unproven conviction that the fetus can feel pain and is an independent being, numerous states have passed laws banning any abortion if it comes after the 20-week marker. Specific surgical procedures used in late-term abortions have been banned because opponents have categorized them as “painful to the fetus.”

The success of this refocusing effort will be determined by whether the principles articulated in the recent Texas case are applied to new cases challenging laws framed as protecting the “humanity of the fetus” with little concern for the pregnant woman. Will the Court look to medical and scientific data to help decide whether such laws unduly restrict a women’s right to choose? Or will the image of a suffering fetus cause them to look beyond the available data?

Jennifer Dalven, the director of the Reproductive Freedom Project at the American Civil Liberties Union, told the New York Times, “The court was crystal clear that politicians can no longer rely on flimsy justifications for abortion restrictions. You have to have evidence that it serves a claimed interest, then weigh it against the burden. That has application to virtually any regulation.”

Judging by the predominance of current evidence, there would not seem to be much dispute. Fetuses are not known to be viable until 22 weeks. Fetuses at an earlier stage are not known to feel pain. But as so many current debates have shown us, legislation is influenced by more than mere science. Perhaps this is true of the Supreme Court, as well.—Martin Levine