November 3, 2016; Brookings Institution

The truism that “all politics is local” looks quite different when it comes to poverty. Contrast the ability of a very divided federal government to overcome their differences and agree on a national education strategy with their complete lack of action when it comes to a national anti-poverty strategy, and you might conclude that many in Congress represent districts with few poor voters. A new report compiled by the Brookings Institution tells us that the gridlock on economic policy does not reflect the local reality that U.S. representatives face.

Although the poverty rate is higher in districts represented by Democrats, most poor people in the United States live in a community represented by a Republican. Taken together, the poverty rate in districts represented by Democrats in 2016 (“blue” districts) was 17.1 percent in 2010-14 compared with 14.4 percent in those represented by Republicans (“red” districts). But Republican districts have more poor residents overall: 25.1 million poor people lived in red districts in 2010-14 compared with 22.7 million in blue districts.

[…]

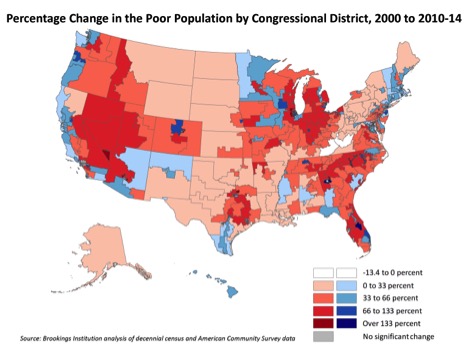

Between 2000 and 2010-14, 96 percent of congressional districts (245 Republican and 175 Democratic districts) registered a significant increase in the number of people living below the poverty line.…Thirty-five districts saw the poor population more than double during that time, and most of those districts (28) were Republican (including House Speaker Ryan’s district, which registered an increase of 102 percent).

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Perhaps, in some districts, the poor are so spread out that they have become invisible. Brookings’ analysis found that “86 percent of districts (213 Republican and 163 Democratic) were home to at least one neighborhood with a poverty rate of at least 40 percent—the threshold that historically demarcates areas of concentrated urban poverty.”

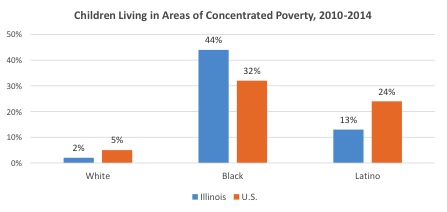

What this means is that a significant portion of the constituency of every member of Congress is poor. Yet many representatives seem to remain unaware or unconcerned. One obvious answer is that this is emblematic of our nation’s entrenched racial bias. Because people of color make up a larger proportion of the poor, they are easy to ignore in many parts of the country.

But we should also not ignore long-term efforts by some to shrink government in favor of a market-based society. Sociologist Arlie Russell Hochschild spent five years trying to understand why the poor were of so little concern to so many of our leaders in her study of “Tea Party America.” In Strangers In Their Own Land: Anger and Mourning on the American Right, she suggests that the tendency of the local body politic to ignore poverty nurtures feelings of being left behind and passed over, feelings that isolate and demonize the poor, people of color, and immigrants. The inability of government to move forward and solve problems for all elements of our society suggest to them that government is more a part of the problem than the solution. Constituents who believe this turn out to support politicians who look to shrink government, limit programs that might improve the life of the poor, and allow market forces play out as they will.

The national stalemate on responding to poverty does not reflect reality, and our new president and Congress will have to face it. The stridency of the current campaign holds few signs that help for the poor is on the way.—Martin Levine