January 3, 2017; Chicago Tribune

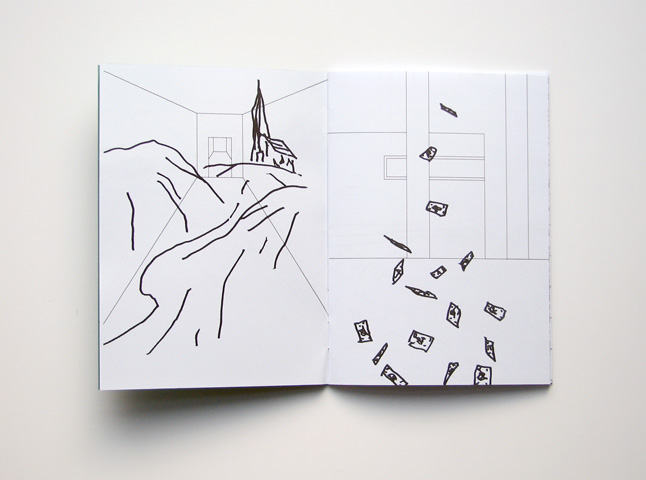

For the universities and social service organizations in Illinois, 2017 isn’t looking like a very good year. As of the stroke of midnight on January 1st, the state once again had no budget and funding was cut off. With state leadership no closer to ending this ongoing political war, the outlook for a quick end to the pain seems very dim.

Illinois was without a budget for an entire year until a stopgap agreement was reached last July. The funding plan guaranteed a full year of funds for public (K-12) schools but committed only six months of funding for colleges, universities, and social service agencies at a level well below “full funding.” When the plan was passed, NPQ observed:

The immediate threat of a government shutdown has passed. State officials can wait until after the November elections to before they again try for a real solution. Those charged with providing essential services have some money to spend but remain without a clear picture of their future and still in need of ways to fund what the state will not for their clients and students.

Underlying the impasse is the dim financial situation in Illinois. Years of shortchanging the state’s pension funds, topped off by the Great Recession’s market crash, left them underfunded by more than $100 billion. Years spent balancing the state’s checkbook by delaying payment of state bills have left it owing more than $11 billion. For Republican Governor Bruce Rauner, solving the impasse requires getting action on his reform agenda, which includes capping property taxes, limiting the bargaining rights of unions, curtailing the state’s workmen’s compensation system, and other elements of the Republican playbook. The Democratic legislative leadership argues that none of these actions will solve the budget crisis, so they should not be part of the budget discussion. They want the governor to propose a spending plan and support an income tax increase. The two sides sit unmoving, waiting for the other to blink, and while they stare at each other, those who do the work of the state are left with an immediate problem.

The year the state went without a budget left many colleges and social service agencies significantly weakened as they scrambled to operate without expected state funding. Those with reserve funds drew them down and now face new challenges with coffers they haven’t been able to refill. Some borrowed funds to tide them over, adding additional cost to their strapped budgets without having received full repayment from state grants. Those without these fiscal safety nets were forced to cut expenses, often shedding important personnel and limiting or ending services. All were left weakened, hoping that a solution for the state’s problems would be found.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

While the interim budget provided some relief it was not a solution. According to the Chicago Tribune,

The situation represents a double whammy for universities and social service providers already operating on shoestring budgets. While the money released under the stopgap budget helped stem some of the losses, much of those funds went to backfill costs racked up during the year they spent waiting on state dollars. As a result, little of the emergency funding was actually used for programs provided during this budget year. Meanwhile, the debts continue to pile up.

Randy Dunn, president of Southern Illinois University, described how dire the situation is for organizations dependent on state funding now that no budget solution appears in sight: “I understand it may be very difficult to see a path by which we get a budget done, possibly even for the next two years. We understand that political reality. What we won’t be able to live with is going that period of time without some sort of stopgap appropriation or more limited spending authority. It’s an untenable situation.”

For Metropolitan Family Services, the budget argument means figuring out whether it’s possible for the organization to keep a program serving the victims of domestic violence going without state funds. The state’s funding commitment to these services had been $600,000. For the first six months of the fiscal year, they received only $54,000, with no more expected due to the budget impasse. According to Karina Ayala-Bermejo, who directs the agency’s Legal Aid Society, “That may seem insignificant, but it’s hugely significant for the work that we do. We are in a bit of a dire situation. This year we have made huge cuts and painful decisions prior to this, and now we’re talking about stripping down even further.”

Similar difficult conversations are taking place in the offices of every organization that does the state’s business. For the political leadership, there appears to be little urgency. No meetings between the two sides are on the calendar and no signs of weakening have emerged. For those whose lives depend on state-funded services, this is a crisis. Can anyone who has the power to fix the problem hear them?—Martin Levine