Editors’ note: This article was adapted from Meeting the Job Challenges of Nonprofit Leaders: A Fieldbook on Strategies and Actions (Center for Creative Leadership, January 2015), and is from the Nonprofit Quarterly’s spring 2016 edition, “Strategic Nonprofit Management: Frameworks and Scaffolding.” It was first published online on April 18, 2016.

There is nothing like understanding that your decisions and actions will be consequential to reinforce learning. Therefore, learning on the job, with a lot of feedback and reflection, can be a very rich source of leadership and management development. Research reinforces over and over the value of learning through risk taking and reflection, but how exactly do we construct the cycles of consideration in our experiences to encourage continuous and humble but increasingly confident development?

This article addresses some just-in-time leadership development strategies that can provide nonprofit leaders with opportunities to shift their perspective and stretch their current repertoire of practices and competencies. It is a guide to self-coaching on leadership and management issues. The leadership issues revolve around driving change, aligning programs with mission, thinking generatively, creating a desired culture, developing strategic partnerships, and understanding one’s impact on others. The management issues revolve around getting to results, developing tactical solutions, supervising individuals and teams, and managing resources.

At Community Resource Exchange (CRE), our approach is based on the belief, borne of experience, that individuals can make significant changes on their own if equipped with the right tools, which include the following:

- The right questions to ask of themselves;

- Some turnkey practices and tactics; and

- Relevant application tools for specific issues.

Our aim is to provide nonprofit leaders with tools incorporating these elements, so they can self-coach and learn from actions they take while on the job. In that self-coaching they must engage in reframing and “1-2-3” steps.

Reframing. Reframing is a common coaching methodology. The ability to shift one’s perspective or paradigm can unlock a fresh approach to a daunting challenge. A nonprofit leader can learn to develop the art of reframing situations and problems so that new solutions emerge.

“1-2-3” Steps. The idea of “low-hanging fruit” led us to the notion of taking the first few relatively easy actions that one can take to address a given challenge. These steps move a leader from understanding to action and change, and are akin to “application assignments” that are used in coaching and action learning. Some of them contain self-training and self-learning components.

But these actions should be informed by what we call relevant application tools.

You will see this approach reflected in the examples provided over the next pages. The challenges portrayed in those examples are not simple or linear; as is true in the nonprofit leader’s world, they are multidimensional and complex. There is no one solution for these challenges, and certainly no magic bullet to address them. You will note, as well, that some of the strategies we propose dovetail one with the other—and, at times, a strategy can apply to several challenges.

Our hope is to create an avenue for the nonprofit leader to begin addressing those challenges on his or her own and in his or her workplace. There are “low-hanging” developmental opportunities one can find within oneself, within the workplace, and among one’s network of colleagues and friends.

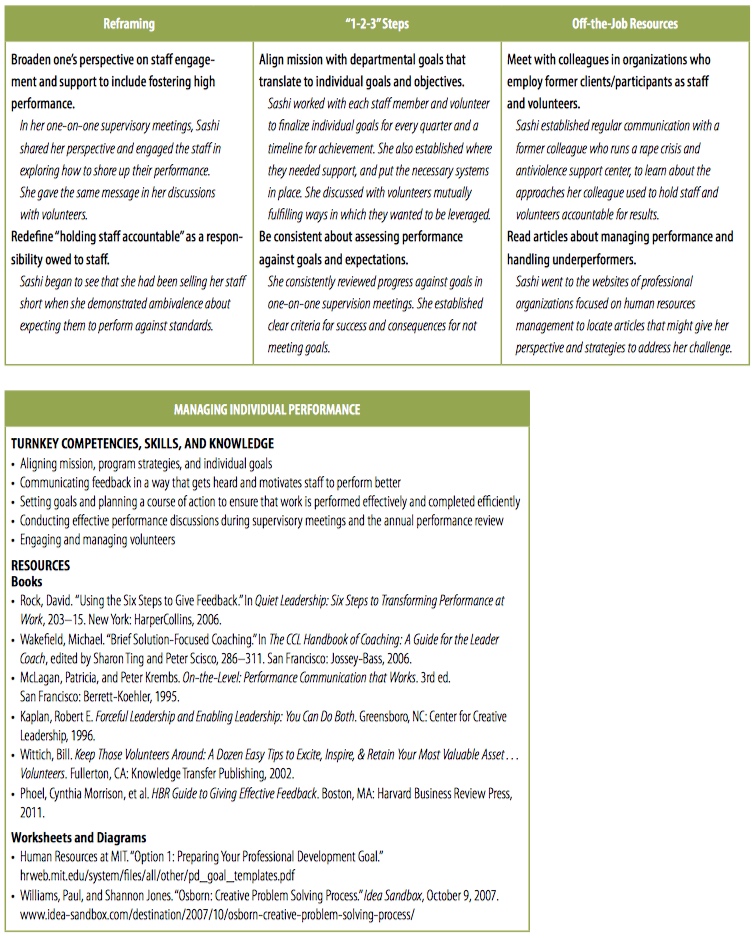

Managing Individual Performance

Issue: Sustaining high performance standards, so that staff members achieve program and organizational goals, can be challenging in organizational cultures where there is a push and pull between getting to results and maintaining an environment where staff feel supported.

Why it matters: Holding staff accountable for results is key to sustaining organizational effectiveness and achieving outcomes. In addition, it would be a disservice to the staff’s professional growth if the leader failed to do so.

“Deliver or else…???”

Sashi is the executive director of an organization that helps Asian women (primarily of South Asian descent) who are victims of domestic abuse. With a small budget of $300,000, the organization has programs ranging from a transitional home for displaced women and children, counseling services for battered women, a legal initiative that provides free legal clinics to women who cannot otherwise afford counsel, support groups to help women overcome abuse, and a public initiative that educates the broader community and law enforcement personnel on how the cultural norms and social values unique to this community impact women facing domestic abuse.

The organization does a lot with very little, and relies heavily on its staff and volunteers. In addition, staff members are not paid well in comparison with other larger nonprofits that do domestic violence work or state agencies that support this work on a statewide basis. Staff members and volunteers are from the community; some are, themselves, survivors of domestic abuse or have other difficult personal circumstances. While dedicated to the mission, many staff members do not perform at the level necessary to get all the work done. In addition, holding volunteers accountable—given they are unpaid—is challenging. Sashi is acutely aware of this fact, and she feels ambivalent about holding her staff and volunteers to the required performance levels, knowing their personal circumstances and relatively low or nonexistent salaries.

Although Sashi was challenged by the issues of managing individual performance, she made time to focus on applying the following approaches, which paid off for all concerned:

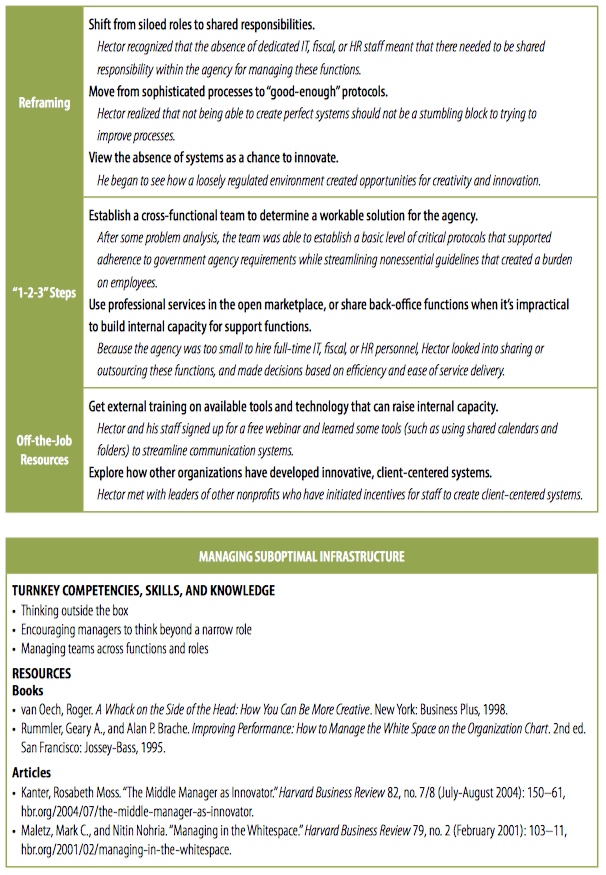

Managing Suboptimal Infrastructure

Issue: Nonprofits often lack resources to invest in systems that improve efficiency in the long run, such as finance, human resources, information technology, and knowledge management; they have to manage these functions on an ad hoc basis.

Why it matters: Nonprofits must get to results and manage program and operations even amid these gaps.

“Sometimes we hold it together with spit and baling wire.”

Hector is the relatively new program director of a small, community-based preventive-services agency providing parent education, counseling, and casework to prevent children going into the foster care system.

As the organization is funded and subject to review by a government agency, employees are required to meet various protocols and standards, such as maintaining two contact sessions per week for each client, submitting case notes within twenty-four hours, and weekly clinical supervision.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Hector found that his agency’s internal systems and processes, especially IT and HR, were not organized to support the government agency’s protocols, resulting in staff who sought to comply with these requirements feeling overwhelmed by the paperwork and sometimes resigning as a result. In a few cases, he also discovered the troubling practice of staff indicating client contact simply to meet the reporting requirements. Without a full-time HR manager, dealing with personnel and disciplinary challenges became an ongoing headache. At the agency level, they were falling behind on timely and accurate contract deliverables and at risk of losing their contract.

To address the challenge of suboptimal infrastructure, Hector stepped back from the day-to-day minutiae of infrastructure concerns and tried the following approaches, with good results:

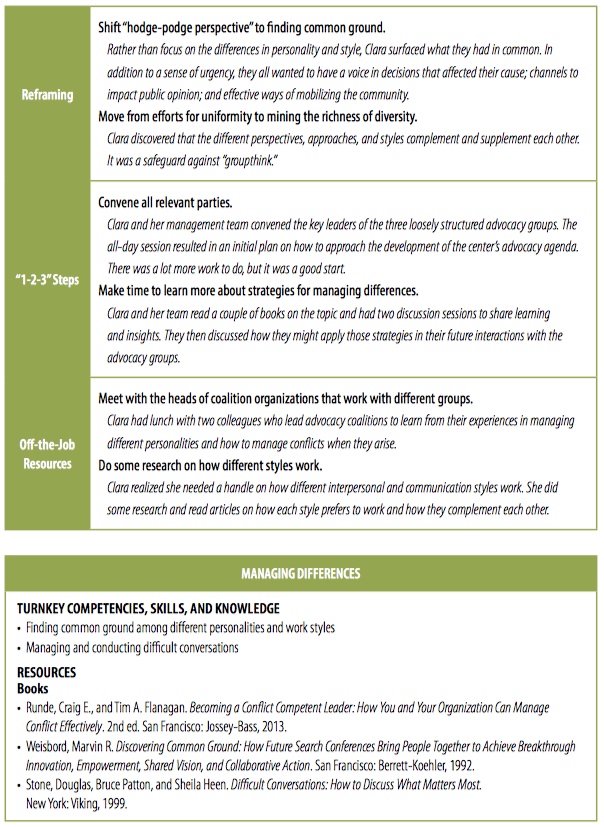

Managing Differences

Issue: Nonprofit leaders partner regularly with a complex mix of stakeholders mentioned earlier. Each of these stakeholder groups has its own goals, concerns, and agendas. Nonprofit leaders must be adept in working with individuals and groups who have diverse personalities and work styles, above and beyond differing agendas, interests, and persuasions.

Why it matters: Nonprofit agendas are often cross-sectoral, requiring collaboration with multiple partners for success. A focus on one set of stakeholder interests over others has the potential to distract leaders from mission-critical activities or from the fundamental goal of client impact. Although managing these personality and style differences may be a challenge, such diversity can also be a rich source of stimulating perspectives and creativity. If one can harness this wealth of diverse ideas and approaches, then so much the better for the sector.

“What a cast of characters!”

Clara is the executive director of a large community center based in a major city. The center is known for housing and advising various start-up groups that are trying to establish themselves and then move on to their own offices, as well as for its generous meeting and program facilities. More recently, the center began to develop an advocacy agenda to support immigration reform. Then, other interest groups voiced their desire to be part of the center’s advocacy agenda—more specifically, for the LGBT community and for environmental justice.

As Clara began meeting with the leaders of these groups, their passion and determination for their specific issues became evident. As discussions progressed, a clash of personalities and styles surfaced. In addition, these leaders represented a range of generations, including millennials, Gen Xers, and baby boomers, who are influenced by their period’s economic, political, and social events—resulting in divergent opinions on almost all issues. Their preferred approaches to advocacy and community organizing for immigration reform, LGBT issues, and environmental justice differed, their perspectives about what might work were not always compatible, and their interpersonal styles varied. “What a cast of characters!” Clara thought at first. However, she realized that these leaders cared deeply about issues that mattered to their constituencies; and one thing they had in common was their sense of urgency about the issues they cared about. If she and her small management team could facilitate those meetings in a way that minimized unproductive exchanges and leveraged the strengths of each leader, then they could find ways to support these advocacy concerns.

After some discussions with her management team about the challenge of managing differences, Clara tried the following approaches, and was pleased with the results:

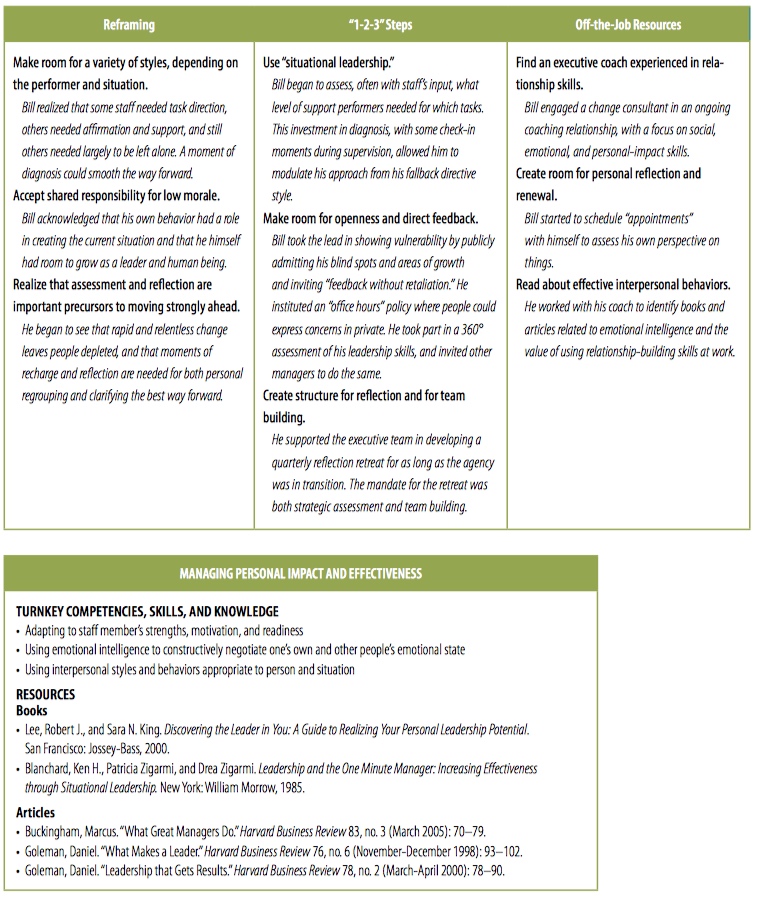

Managing Personal Impact and Effectiveness

Issue: Nonprofit leaders tend not to make the time to pause and reflect on their own leadership and management style and to consider how this impacts their relationships with clients, colleagues, partners, and other stakeholders.

Why it matters: Experience as well as research show that leaders who are more “behaviorally complex”—that is, those who have greater self-awareness of their own behavior and have built an adaptive style—are more effective in leading others to decisions, sustaining long-term relationships, and getting to results.

“Take me or leave me.”

Bill was hired to be the turnaround artist at a settlement house that was losing programs and revenue under a popular but ineffective outgoing leader. He spent a year leading the board and executive team in identifying the agency’s core lines of business, consolidating programs, and rebuilding funder relationships. Clear performance benchmarks were set for staff at all levels, and those who did not meet expectations were transitioned to different roles or let go.

While performance and revenue began to rebound after a year, morale took a nosedive. When interviewed by a consultant, even high-performing staff complained of Bill’s authoritarian and overly directive style, and of not being listened to when they had good ideas to share. Staff said they were staying because they had a commitment to mission, but several were actively engaged in a job search or updating their resumes. When the consultant shared these results with Bill, his first response was annoyance: “Do they realize what it took to turn this ship around? If they don’t like strong leadership, they are free to work elsewhere.”

On further reflection, and after several discussions with the consultant and his board chair, Bill decided to address the challenge of personal impact and effectiveness. He tried the following approaches, with good results:

Managing Burnout

Issue: All the challenges that come with functioning in a high-demand, low-resource environment exacerbate the nonprofit leader’s level of stress. Additionally, lack of time for self-care impacts the ability to cope with stress.

Why it matters: Sustained high levels of stress have a direct impact on productivity, effectiveness, and the ability to “stay in the game” for the long haul—a combination of symptoms referred to as burnout.

“I feel like I’m in a 24/7 spin cycle.”

Brian always prided himself on his stamina for work. As a classic achiever, he thrived on accomplishment; however, after a year of being a new executive director at a grassroots advocacy group, he began to notice some changes in his mood and energy. He wasn’t able to sleep well, home and family commitments began to be neglected, and, even in “leisure moments,” he found himself thinking about uncompleted tasks and imminent deadlines. Friends told him he looked and sounded anxious, which only added to his stress level. As someone deeply motivated by the mission of his chosen organization, he was surprised to find himself having fantasies about quitting and doing something completely different with his life. After speaking with his mentor about some of his feelings and behavior, Brian realized that he needed to address and manage stress in his life.

Addressing the challenge of burnout was a real struggle for Brian, but after much reflection he gathered his energies toward the following approaches, which he later found rewarding.