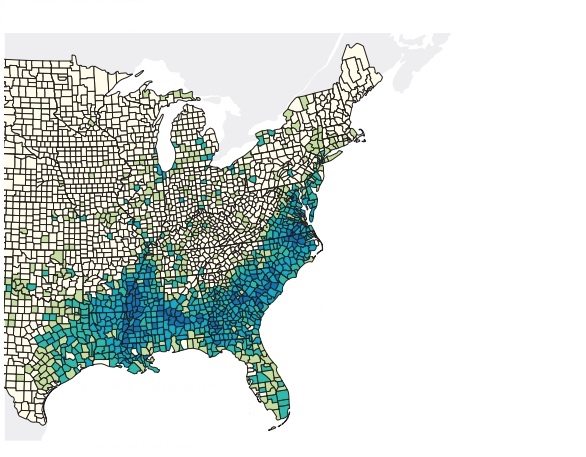

The message of the first report in a planned “As the South Grows” series on giving in the Deep South has been repeated so many times, we figure something has to be getting in the way of its being heard. So, we are going to start with one of its charts, showing the disparity in per capita grantmaking between the Alabama Black Belt and the Mississippi Delta and the rest of the United States.

The National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy (NCRP) and Grantmakers for Southern Progress at the Neighborhood Funders Group (GSP) teamed up to produce As the South Grows: On Fertile Soil. Its premise and overall point is that the Deep South has been neglected by philanthropy, particularly as regards investments in grassroots power-building, the very activity arguably most likely to shift entrenched political dynamics. But, as the report points out, the efforts are there to be funded.

In small towns across the Alabama Black Belt and the Mississippi Delta, movements to establish community control over schools, economic development and political institutions pit grassroots networks against centralized power, which still rests in mostly white, wealthy, male hands. In the decades since the Civil Rights Movement, national foundation interest in the rural South has waxed and waned, and Southern foundations have focused on funding direct service work instead of systemic change strategies with the most potential for long-term progress.

The report, written by Ryan Schlegel and Stephanie Peng, is full of powerful firsthand commentary and stories from Southern activists, including Ivye Allen of the Foundation for the Mid South, which has for decades been supporting those very groups and trying to convince other funders to come to the region with higher and more consistent higher levels of funding.

“People think of the South and think there’s no capacity there. Not true. People have the skill sets; some of them, more than we know, have book knowledge. But they also have a lot of experience, even if they don’t have the technical aspect of it,” explained Allen. “Those leaders are going to continue to be there, whether we are in there investing or not. So how do you help people who don’t look at you as just a handout but look at you as a partner in helping to move their respective communities forward?”

You certainly don’t do so by showing up only periodically. In fact, that is an excellent way to depress capacity in the groups you would otherwise support—if only they had the capacity. (You get the picture.)

The report goes on to say that some foundations and donors “disregard Southern leaders because these individuals seem to lack the educational credentials or formal capacity that grantmakers expect from experienced nonprofit executives. Sometimes foundations and donors defer to existing power structures by working only with established political, business or social sector leaders.”

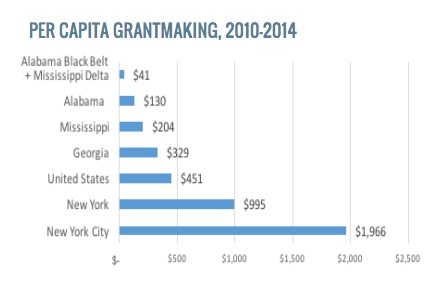

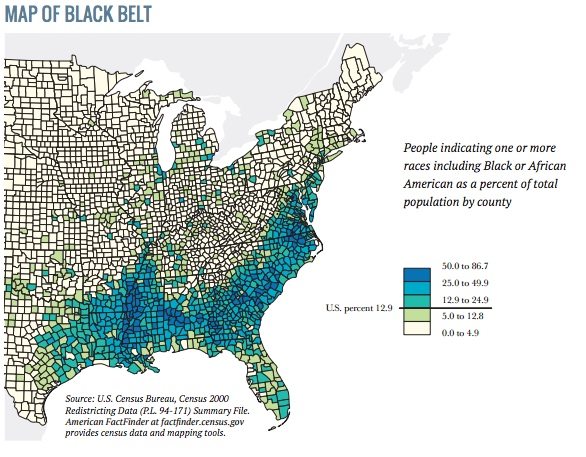

Given the lack of funding for organizing in the area, the availability of groups to fund, and the capacity and history of the struggle for civil rights in the region, here is another chart from the report that, combined with the first chart, should make founders interested in social justice cringe.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

The implication of this is that funders do not invest in homegrown power-building efforts in the Black Belt because they are not drawn in the image of the more-built-up grantees they know well and favor.

But, besides being the right thing to do, why should progressive funders make more permanent and larger commitments to community-driven activism in the South? The report ventures a guess that the rest of the country could learn a little something:

The South is…home to some of the most vibrant and promising systematic change efforts at work in the country, Our new national reality of unified, reactionary, antidemocratic government has been a reality for Southerners off and on for more than a generation. Therefore, national and non-Southern organizations have much to learn from their Southern counterparts.

Southern nonprofits are dynamic, innovative and resilient. By necessity, they work at the intersections of identity and issue, building on the South’s tradition of mutual aid, relationship-building and radical hospitality to change their communities for the better—often without much in the way of philanthropic resources.

Additionally, lest anyone forget, we are still one country:

The time to invest in Southern equity work is now. With the right investments in sustainable social justice infrastructure, progressive candidates will be able to leverage the demographic changes in the South for long-term, region-wide change. Just as the South birthed a nationwide movement for civil and human rights in the 20th century, Southerners’ potential for transforming their communities and our country in this century is immense.

The report’s authors still believe that the habit of underfunding the Deep South can change. They go on to provide a list of do’s-and-don’ts for those interested in investing in the area and a few resources in the form of foundations that can act as guiding partners. One is the aforementioned Foundation for the Mid South, but local community foundations are also referenced as good potential partners.

Below, we’ve reprinted the steps for positive action; they make enormously good sense.

- DO search for and fund Southern organizational leaders who represent the communities they serve. For example, an organization that purports to serve the African-American community and is led only by white people may not be the most effective way for a grantmaker to invest in a better future for that African-American community. This is not to say that white leaders cannot be advocates for their Black neighbors, nor is it to say that men cannot do so for gender justice work nor heterosexual people for their LGBTQ friends and family. Indeed, they can and they do so in the South. But any Southern funding strategy must reckon with the importance of organizational leadership that is drawn from the communities the organization serves.

- DO prioritize leaders and organizations that have the trust of their community as represented in relationships and the influence to get people to show up and speak out. Organizations without the sufficient trust capital—built with time and hard work—to fill a funder listening session, for example, may not be able to leverage foundation resources effectively. Relationships, often those that go beyond professional transactions and into the territory of personal trust and mutual understanding, are a crucial cultural component of nonprofit work in the South. In fact, without them, sustainable long-term progress will be impossible. This kind of trust capital can be difficult to measure, which is why relationships with nonprofit and community leaders are so important to understanding this dynamic.

- DO support Southern community leaders and organizations that are able to articulate how identity, history and politics combine to suppress the power and prosperity of their communities. Their analysis may not be communicated in ways a foundation program officer is used to hearing from sector thought leaders or academics. But the analysis is there if one listens. How are women, LGBTQ people, people of color, immigrants and poor people excluded from community life? How does a community’s history live on in decisions made today? One doesn’t need an advanced degree in sociology to answer these questions thoughtfully and informatively.

- DO look for networks of collaboration, resource-sharing and co-strategizing that already exist. It took the authors of this report more than six months of conversations with community organizers and nonprofit leaders across the rural Deep South to begin to perceive the breadth and depth of the connections among them across issue and geography. It required the full-time work of more than two staff members and the development of trusting relationships. Often national organizations (which may not have as much time or resources to spend) look for formalized, publicized networks of nonprofits as evidence of power-building infrastructure. But Southern history is fraught with examples of well-meaning organizations provoking detrimental and long-lasting backlash. Funders need to consider the impact of that history on Southern nonprofit infrastructure. Before deciding that no network capacity exists there, ask what you may not be seeing. Southerners themselves understand how to live within, build power without and change unjust systems. And Southerners themselves must lead philanthropic strategy development and execution.

- DO provide flexible, multi-year funding and capacity-building support. Grantees need long-term commitments from foundations and donors to plan for long-term strategies. This doesn’t mean support should come without concrete expectations. Funders can empower Southern organizations by providing capacity-building support that enables them to secure more funding (e.g., setting up a fiscal sponsorship).

One final “do”—do read this report and those that follow, and let’s start to change this decades-long status quo in philanthropy.