October 11, 2017; Next City

Increasingly, especially for eastern and Midwestern cities, land banks are part of the landscape of city government. But this is a very recent development. Just a decade ago, fewer than a dozen land banks existed in the United States. Now, there are well over 100, with land banks especially prevalent in the states of Michigan, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and New York.

Philadelphia has had a land bank agency since 2013, but it only just hired an executive director last month. The person hired, Angel Rodriguez, hails from the Asociación de Puertorriqueños en Marcha, a north Philadelphia community development corporation that has operated as a community-based advocate for Philadelphia’s Puerto Rican community since 1970. Rodriguez’s community background could be important, because, when it comes to land, things can often get heated, even when there is positive intent and the best of democratic structures.

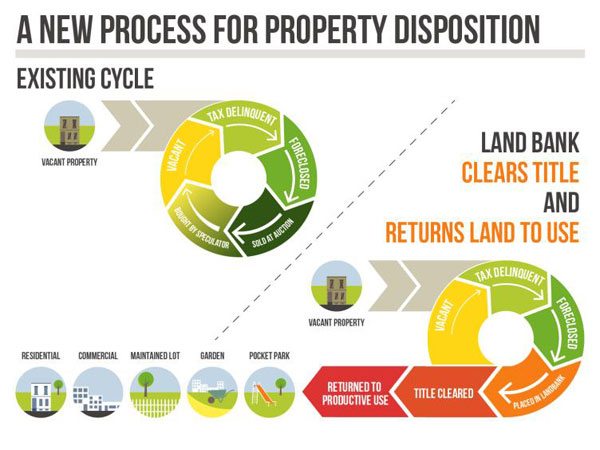

Philadelphia is a city of contrasts. Some sections of the city are thriving, but there are still 43,000 abandoned or vacant lots, reports Next City contributor Cassie Owens. The land bank, it is hoped, can help ensure that public planning oversees the reintegration of thousands of vacant lots into the city’s social fabric in a way that corresponds to city goals, such as finding ways to place the land back into productive use while also ensuring that affordable housing is made available for city residents.

In considering the land bank in Philadelphia, some history is helpful. As Dan Kildee, the one-time county treasurer and present congressman from Flint, Michigan, points out, before land banks were common, land ownership, particularly in cities suffering from high levels of vacant property like Flint, could be wildly chaotic. Kildee says that as of 1999, there were exactly four land banks in the country. Many cities, including his hometown, would find foreclosed properties advertised for sale at bargain-basement prices on infomercials.

“It had become a system that was really a bonanza for out-of-state speculators,” Representative Kildee recalls.

In Flint (Genesee County), Kildee says that the vision behind their land bank “was based on the belief that just quickly selling property to whoever is in line is not the best solution. It’s to sell the property to the responsible property owner.” By ending the auctions and keeping tax lien foreclosures off the market and under public ownership, Kildee and Flint were able to regain control of the planning process. In the first decade after the Genesee County land bank started in 2004, the land bank was able to rehabilitate and sell over 5,000 residential and commercial properties, dispose of another 1,662 vacant lots, and demolish nearly 5,000 dilapidated buildings.

The land bank, of course, did not solve all of Flint’s problems by a long shot. And it certainly didn’t protect the city from lead poisoning in its water. But the land bank did help stabilize the land market and restore public control to land use planning. Other communities took notice—which is why today there are well over 100 land banks in the United States.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

That said, land banks are not without their challenges. A land bank, after all, is a government agency subject to pressure from developer interests. In Pittsburgh, such concerns led community activists to oppose the chartering of a land bank until the resolution creating the land bank was modified to broaden community input and expand the governing board.

Rodriguez, in taking charge of Philadelphia’s land bank, is well aware of these challenges and is proceeding cautiously in his new position. Rodriguez says:

We have to be that agency that really is doing the checks and balances and culling through the sheriff’s sales to make sure that identified properties do not go up for auction. Also, making sure that this agency has an awareness of all of our critical strategic partners in the community. That’s not just our elected officials, but local nonprofits and civic agencies.

Frank Alexander, an Emory law professor and co-founder of the national nonprofit Center for Community Progress, which provides technical assistance to land banks, as well as author of the leading book in the field on land banks, notes that:

The ability to be strategic is key. […] The biggest mistake a land bank can make…is to take in a whole lot of land when it doesn’t know what it’s going to do with it. I don’t recommend that any land bank build up a staff, then figure out what to do with that staff. A land bank should build operational capacity in accordance with the inventory that it’s bringing in.

As Owens notes, however, Philadelphia’s goals are ambitious. The land bank authority’s board, of which Rodriguez was a member before becoming executive director, has set five-year targets that forecast adding 7,727 publicly owned parcels to its holdings and another 1,650 tax-delinquent properties. Owens adds, “The agency also has outlined a mix of types of properties for its disposition process. Sixty-five percent of land returned for active use will be for housing, and in an effort to ensure affordability, only 25 percent of that won’t be restricted by income brackets.”

Between managing these high expectations and balancing community and city government interests, Rodriguez and his land bank authority colleagues are sure to have their hands full. In his first week on the job, Rodriguez observed: “I feel like I’ve been here two weeks…[but] I realized last night that it was only three days.”—Steve Dubb