October 21, 2017; Wired UK

China’s State Council plans to launch a new system for rating its citizens’ “trustworthiness” in 2020. The Chinese government first released its plan for a national “trust score” system on June 14, 2014, in a document titled, “Planning Outline for the Construction of a Social Credit System.” (NPQ first wrote about it last year.) The policy states, “It will forge a public opinion environment where keeping trust is glorious. It will strengthen sincerity in government affairs, commercial sincerity, social sincerity and the construction of judicial credibility.”

The Chinese government says it needs to do something to increase trust. China doesn’t have a credit score system, so the majority of its citizens cannot get credit. Further, micro-corruption is rampant: “According to the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), 63 per cent of all fake goods, from watches to handbags to baby food, originate from China.” In February 2017, China’s Supreme Court revealed that it banned 6.15 million citizens from taking flights over the previous four years and 1.65 million from taking trains for “social misdeeds.”

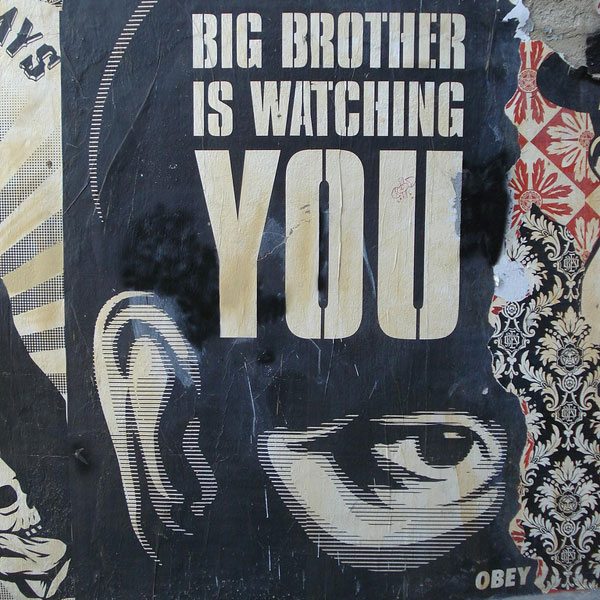

But critics call it “gamified obedience.” According to Rachel Botsman, who excerpted an article for Wired UK from her book, Who Can You Trust? How Technology Brought Us Together and Why It Might Drive Us Apart, this system would monitor and evaluate your daily activities—“what you buy at the shops and online; where you are at any given time; who your friends are and how you interact with them; how many hours you spend watching content or playing video games; and what bills and taxes you pay (or not)”—to create a Citizen Score. Ratings will be compared against the whole population to determine eligibility for social goods. Further, a person’s score is affected by the scores of their online friends; in other words, “if someone they are connected to online posts a negative comment [online], their own score will also be dragged down.”

Participation is currently voluntary but will become mandatory in 2020. Millions of people have already signed up, ostensibly for the perks of a high score. In fact, “higher scores have already become a status symbol.” For example, according to Sesame Credit, one of the two companies conducting social credit pilots,

If their score reaches 600, they can take out a Just Spend loan of up to 5,000 yuan (around £565) to use to shop online, as long as it’s on an Alibaba site. Reach 650 points, they may rent a car without leaving a deposit. They are also entitled to faster check-in at hotels and use of the VIP check-in at Beijing Capital International Airport. Those with more than 666 points can get a cash loan of up to 50,000 yuan (£5,700) … get above 700 and they can apply for Singapore travel without supporting documents such as an employee letter. And at 750, they get fast-tracked application to a coveted pan-European Schengen visa.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

On the other hand,

People with low ratings will have slower internet speeds; restricted access to restaurants, nightclubs or golf courses; and the removal of the right to travel freely abroad with…“restrictive control on consumption within holiday areas or travel businesses.” Scores will influence a person’s rental applications, their ability to get insurance or a loan and even social-security benefits. Citizens with low scores will not be hired by certain employers and will be forbidden from obtaining some jobs, including in the civil service, journalism and legal fields, where of course you must be deemed trustworthy. Low-rating citizens will also be restricted when it comes to enrolling themselves or their children in high-paying private schools.

Alibaba, which runs Sesame Credit through a financial affiliate, generates the social credit score through a secret proprietary algorithm, which takes five factors into account: credit history; fulfillment capacity, or the ability to pay one’s debts; personal characteristics (such as phone number and address); behavior and preferences (shopping habits); and interpersonal relationships (including sharing “positive energy” messages online).

The government documents summarize the social credit system as one that will “allow the trustworthy to roam everywhere under heaven while making it hard for the discredited to take a single step.” Botsman writes, in response, “The new system reflects a cunning paradigm shift…instead of trying to enforce stability or conformity with a big stick and a good dose of top-down fear, the government is attempting to make obedience feel like gaming.”

But, she also notes, “Governments around the world are already in the business of monitoring and rating.” In the US, FICO (credit) scores are used to determine financial decisions, the National Security Agency digitally follows its citizens, and data-collecting giants like Google, Facebook, and Instagram—even FitBit—already collect our behavior and preferences. Last year, an app called Peeple launched that allowed people to assign ratings and reviews of people they know, which adds up to a “Peeple Number.” Once your name is in the system, you cannot opt out. For those familiar with the British sci-fi series Black Mirror, the consequences of such a system play out in the episode titled “Nosedive.”

Botsman concludes that while it may be too late to stop this impending new reality, one thing we can do is make this one-way rating system into a two-way system by rating the raters. Or, as Kevin Kelly writes in his book The Inevitable, our choice is between surveillance and “coveillance.”—Cyndi Suarez