October 30th, 2017; New York Times, Native News Online

“We had reached a point in history where we could not tolerate the abuse any longer, where mothers could not tolerate the mistreatment that goes on the reservations any longer.”

Dennis Banks, 1974

Dennis Banks, an Ojibwe co-founder of the American Indian Movement (AIM), died at the age of 80 last Sunday of complications from pneumonia following open-heart surgery. Banks lived on Ojibwe land at Leech Lake, where he was born and grew up, in northern Minnesota.

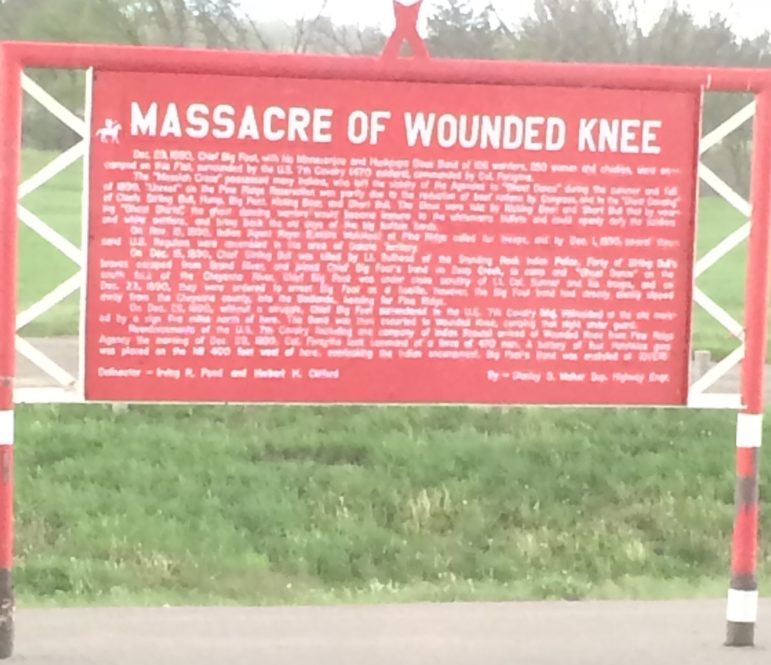

Banks is best known for his role in AIM, which he cofounded in 1968. A year later, AIM staged an 19-month occupation of Alcatraz in San Francisco Bay. Other key events, where Banks participated directly, include a six-day takeover of the Bureau of Indian Affairs in Washington in 1972 and an armed 71-day occupation of Wounded Knee, South Dakota, on Lakota land at Pine Ridge the following year. Wounded Knee was the scene of the last major US military action in the so-called American Indian Wars, in which US troops massacred 350 Lakota men, women and children.

Regarding the 1973 standoff at Wounded Knee, National Public Radio’s Emily Chertoff recalled:

Federal marshals and National Guard traded heavy fire daily with the native activists. To break the siege, they cut off electricity and water to the town, and attempted to prevent food and ammunition from being passed to the occupiers. Bill Zimmerman, a sympathetic activist and pilot from Boston, agreed to carry out a 2,000-pound food drop on the 50th day of the siege. When the occupiers ran out of the buildings where they had been sheltering to grab the supplies, agents opened fire on them. The first member of the occupation to die, a Cherokee, was shot by a bullet that flew through the wall of a church.

To many observers, the standoff resembled the Wounded Knee Massacre of 1890 itself — when a U.S. cavalry detachment slaughtered a group of Lakota warriors who refused to disarm. Some of the protesters also had a more current conflict in mind. As one former member of AIM told PBS, “They were shooting machine gun fire at us, tracers coming at us at nighttime just like a war zone. We had some Vietnam vets with us, and they said, ‘Man, this is just like Vietnam.’ “

After the 1973 standoff ended, Levi Rickert at Native News Online writes:

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Banks was indicted for 10 felony counts … After an eight-month trial, Judge Fred Nichol, citing misconduct by the government, dismissed the case and Banks was free.

However, Banks still faced charges of inciting a riot and assault charges … In 1975, Banks was convicted of the charges. He fled South Dakota and became a fugitive. One of his attorneys, William Kunstler, presented then-Governor Jerry Brown a petition—in pre-internet days—with over 1.4 million signatures to grant Banks amnesty. Brown refused to extradite Banks to South Dakota and granted him amnesty. Banks remained there throughout Brown’s administration and later found protection on the Onondaga Nation near Syracuse, New York after Brown left office.

In 1984, Banks turned himself in to authorities. He said, “I don’t know if you can feel discrimination, Judge. I don’t know if you can feel racism. But I do.” Banks received a three-year sentence, but was released on parole after 14 months. Banks remained an activist to the end of his life and spoke against the Dakota Access Pipeline at Standing Rock earlier this year. Banks also wrote an autobiography in 2005 titled Ojibwa Warrior.

The Times’ obituary ungenerously comments that while the “protests won some government concessions and drew national attention and wide sympathy for the deplorable social and economic conditions of American Indians, Mr. Banks achieved few real improvements in the daily lives of millions of Native Americans, who live on reservations and in major cities and lag behind most fellow citizens in jobs, housing and education.”

This seems less than fair. Of course, no one would deny the challenges American Indians face, but so many achievements are missed, including the 1978 Indian Welfare Child Act, which ending the practice of boarding schools that took children away from their families, and the American Indian Religious Freedom Act of the same year, which ended federal interference with American Indians practicing their religious traditions. The rise of American Indians casinos since the late 1980s only benefits a minority of American Indians, but it did generate $31.2 billion in revenue last year. The development of a national network of tribal colleges is also significant. Today, these institutions enroll 88,000 students.

And, if one looks, it is easy to see signs of rebuilding. In Nebraska and Iowa, for example, the Winnebago Nation’s Ho Chunk Inc. economic development corporation generates $230 million in revenue and “employs more than 1,000 people in 26 subsidiaries across the United States and abroad. Its diverse portfolio includes information technology, construction, government contracting, green energy, retail, wholesale distribution, marketing, media and transportation.”

Meanwhile, at Pine Ridge, the scene of both the 1890 massacre and the 1973 conflict and among the poorest communities in the US, a Lakota cultural revival is under way. A Lakota nonprofit incorporated a decade ago, the Thunder Valley Community Development Corporation, is leading a $60-million project to build a sustainable community. The group also teaches both Lakota youth and their parents the Lakota language, which only three percent of Lakota speak fluently.

Nick Tilsen, the group’s executive director, is son of Mark Tilsen and Joann Toll, who met in 1973 at Wounded Knee. The group, notes Sarah Sunshine Manning in Indian Country Today, “seeks to address the many interrelated challenges of the Pine Ridge community…complete with solar powered ‘green’ buildings, sprawling designs of master-planned and indigenized communities, workforce development programs, youth leadership, and food sovereignty practices, all of which are carefully blended with traditional Lakota value systems.”

The group began its work with a challenge: “When are you going to make a way for your people, are you not warriors? It’s time to stop talking and start doing.” Tilsen says the question reflects an awareness of a “disconnect in what was taught in ceremonies, and what was happening out in our communities.” Meeting this challenge is not easy, however. “Our vision,” Tilson observes, “has to be as big as the challenges we are faced with.”—Steve Dubb