Last year in San Diego, 15 nonprofit organizations requested that the City Council adopt six pillars to guide policymaking. These tenets include the right to affordable housing, safety and justice in all neighborhoods, affordable and reliable transportation, an inclusive and accountable democracy, a healthy environment, and the right to prosper and achieve one’s full potential. The organizations asserted that while the details of implementation will require discussion, there should be no issue with the pillars themselves, as they are rooted in the very reason democratic government exists—to promote the well-being of the people.

In the past, nonprofits have often deferred to policymakers. Or, if we do advocate, we focus on a narrowly tailored agenda that connects directly to our own mission. Yet as San Diego and many other communities increasingly recognize, nonprofits need to embrace a broader public voice and role. Otherwise, community needs will continue to play second fiddle to a narrow vision centered on economic growth. And in that economic discourse, expenditures for health, public transit, education, the environment, and quality of life are typically viewed as “costs” rather than investments in developing individual and community capacity.

Defining Success, Measuring What Matters

What can the nonprofit sector do to advance these principles? The time is ripe for widespread adoption of community well-being indicators. As with healthcare, indicators serve as vital signs that monitor life-sustaining functions. These measures translate aspirational visions like the six pillars into actionable goals with metrics to quantify what success looks like for each. The indicators also provide a method by which progress can be tracked over time, signaling when interventions are needed. Globally, many countries use community well-being indicators to guide policymaking, including Canada, Australia, and Bhutan. In the United States, cities such as Santa Monica, San Francisco, Spokane, Pittsburgh, and Rochester have developed indicators to guide community development and policy decisions. Since 1990, the United Nations has calculated annually a human development index, which seeks to assess quality of life using a combination of economic, health and education criteria.

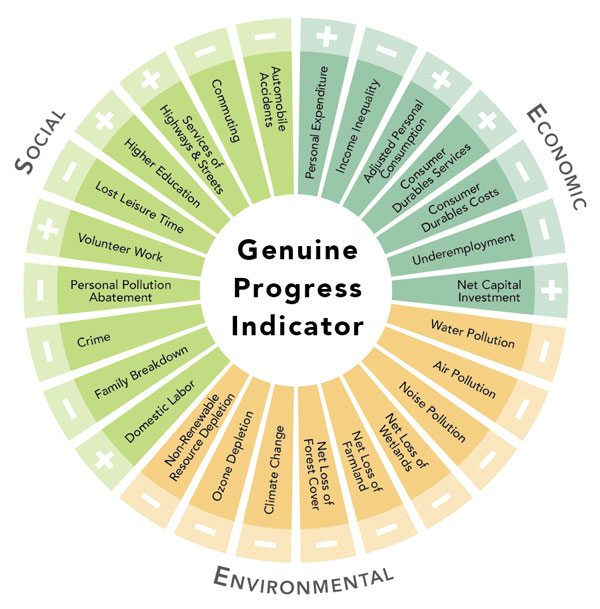

In the nonprofit sector, the Oakland-based nonprofit Redefining Progress has advocated for what it has called a Genuine Progress Indicator (GPI) system since 1995. As the group explains on its website, “The GPI starts with the same personal consumption data that the GDP is based on, but then makes some crucial distinctions. It adjusts for factors such as income distribution, adds factors such as the value of household and volunteer work, and subtracts factors such as the costs of crime and pollution.” Redefining Progress uses dollars as its denominator, which allows for direct comparison with GDP (Gross Domestic Product) numbers. One of the findings: While GDP has continued to rise steadily in the United States since the 1970s; the GPI number has stayed relatively flat. As Redefining Progress puts it, the result of the more complete set of indicators is a “more truthful picture of economic and social progress.”

Of course, no set of indicators is perfect. By definition, indicators are compilations of data about larger systems and concepts that cannot be measured directly (Kim, 2016). For example, the county of Monterey, California measures “health” by aggregating six metrics: residents’ self-reported health, body mass index, life expectancy, high school graduation rate, addiction death rate, and teen pregnancy rates. Coupled with measures from other domains (e.g., transportation, education, housing, environmental quality, safety, equity, and inclusion), these indicators create an index.

The value of a community well-being Index is to measure and track multiple domains of well-being over time. These metrics provide a dynamic, holistic picture of a community’s vital signs. Measures typically cover multiple levels (individual, neighborhood, regional). At the individual level, measures tend to be subjective, asking residents directly about their perceptions, such as how safe do I feel in my neighborhood? At other levels, objective measures tend to use existing data collected for other purposes, such as crime rates, health and education outcomes, and public transit accessibility. This facilitates benchmarking and comparison at the regional, state, and national levels. Government agencies increasingly provide open data sources that make data compilation easier.

Why Indicators?

An indicators approach to community development offers many benefits. On a conceptual level, these multi-dimensional measures reflect the interconnectedness among individuals, communities, businesses, and public policy choices over time. Unlike the Gross Domestic Product, which tracks only a single dimension of the economy (financial), community well-being indicators track the fundamental components that make a society that promotes human flourishing possible. They employ what economist Amartya Sen calls a capability approach, focusing on attainable opportunities for individuals to do and be what they value in ways that simultaneously advance collective well-being. Further, the transparency of this civic engagement approach illuminates the underlying (and often ignored) issue of competing values. Such transparency and dialogue are essential to prevent situations like the Flint water crisis, where financial considerations were clandestinely prioritized over public health.

Well-being indicators also focus attention and align effort. In this regard, they’re similar in intent to the metrics that guide philanthropy’s collective impact initiatives. Yet because these simply prescribe collective goals without determining the manner of achieving those goals, they avoid many of the criticisms that observers have made of the more prescriptive collective impact approach. Ideally, community well-being indicators include goals for policy and promote institutional thinking around designing change in systems that enable communities to more effectively address social justice and the drivers of structural inequality (e.g., racism, homophobia, sexism). They also facilitate inclusiveness, public input, and meaningful engagement of community members from different power levels. An essential component (not always realized) is active buy-in and leadership from the public sector. Many index initiatives have languished due to a lack of public integration. Data are ineffectual without the political will and resourcing to implement needed policy changes and action.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

What Gets Measured Gets Done

What can nonprofit organizations do to promote the adoption of regional community well-being indicators? First, think about what quality of life means to you and your stakeholders. How does your organization promote well-being for individuals and the community, and how do you measure that? Then, research what indicators, if any, are being used in your region now. Who is measuring quality of life, sustainability, and collective impact? Call those organizations with your current partners to act jointly. Coalitions often have more success in gaining the attention of government leaders.

Next, build on lessons learned from other initiatives (Warner & Kern, 2013). Identify existing data in your community that can inform development of comprehensive indicators. How will the voice of diverse residents be heard? A participatory action research approach promotes inclusiveness, ongoing reflection, and stakeholder engagement. Sketch out a strawman framework (imperfect metrics are OK). Start meeting with government agencies and officials to get their input and buy-in. This step is crucial. Without a broad, vocal, and persistent effort that promotes co-creation of the metrics, public officials are unlikely to invest the time, energy, or resources necessary for robust implementation. Framing will be key—how will implementing a community well-being index make their lives easier and inform public decisions? What issues keep them up at night, and how could a comprehensive index help address those problems?

Finally, build processes to keep the measures front-and-center within your organization, your collaborations, public policy meetings, and the media. Speak to your board, staff, and constituents about the ways your organization can support and publicize those collective goals. Simple, visually appealing dashboards can be helpful here. Creative use of technology and social media can also assist with data collection and build public support for a community index. In partnership with your funders, elevate the profile of community well-being indicators by discussing them at regional, state, and national convenings. Create a multi-sector network of people and organizations committed to putting community well-being at the forefront of action and policymaking.

Regional adoption of community well-being indicators is one of the most powerful interventions the nonprofit sector can make at this critical juncture in our history. They showcase who we are and who we want to become, says Tyler Norris, who today directs a $100-million Well Being Trust funded by Providence St. Joseph’s Health (Norris, 2014). By creating a comprehensive, measurable agenda through transparent and inclusive processes, communities can drive systemic change on multiple levels simultaneously—individual, organizational, community, national, and global. A community well-being index invites a new understanding of economics by shining a light on the nourishing elements that make an economy that truly works for all possible. Just as a brain can function only when it is nourished by the heart and lungs, so too does economic success depend on thriving people and neighborhoods. It’s time to raise the profile of the vital signs that make this success possible.

References

Kim, Y. (2016). “Community wellbeing indicators and the history of Beyond GDP.” Ithaca, NY: Cornell University.

Norris, T. (2014). “Healthy communities at Twenty-Five: Participatory democracy and the prospect for American renewal.” National Civic Review, 102(4), 4-9.

Warner, K. & Kern, M. (2013). “A city of wellbeing: The what, why, and how of measuring community wellbeing.” Santa Monica, CA: City of Santa Monica Office of Wellbeing.

Resources

- Community Indicators Index. Community well-being measurement resources, including sample indicators and a searchable database of indicator projects throughout the United States and Canada.

- Community Indicators Victoria.

- Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (2011). Compendium for OECD Well-being Indicators

- Toolkit for building and sustaining coalitions

- 2016 Distressed Communities Index: An analysis of community well-being across the United States. Economic Innovation Group.