The public remains largely uneducated about the variables of various nonprofit business models, and it is our job to make sure that problem does not persist. Looking at organizations through the lens of their numbers requires understanding what they do and how their work is supported. Each line of revenue has its own transaction costs, and each program type has its own cost requirements. Some nonprofits have a great deal of unrestricted monies, and others have almost none. Because of the diversity of organizational types in the sector, managing these various models can get very complicated.

Last week, I wrote a newswire about an article printed in a local newspaper that purported to address the relative effectiveness of local nonprofits by looking at their overhead ratios. To be fair, the author did not use the word “overhead,” but he asked, “When you contribute to a charity or a nonprofit organization, do you ever wonder how much of your contribution goes to help the beneficiaries of the charity and how much goes to the employees who manage the charity or the professional fund raisers who solicit donations,” which gets to the same principle.

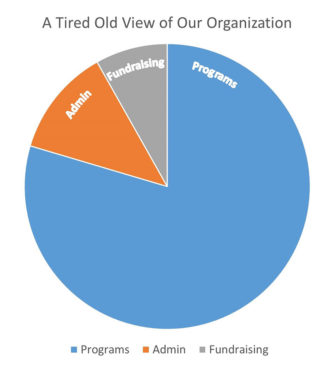

But the numbers we were asked to compare don’t help us get to that for many reasons. Here, as was exhibited in another popular article we published entitled “A Graphic Re-visioning of Nonprofit Overhead,” is how an overhead rate ratio was figured when it was still being used as a standard:

In other words, even if the construct is long outmoded as a proxy for ethical or impactful management, “overhead” is generally understood as the portion of overall expenses devoted to fundraising and administration. If a business journal applied the same performance standards to a low-margin supermarket and a high-margin tech company, it would get raked across the coals, but it’s somehow OK to apply the same standards to all nonprofits.

In the article in question, the ratios were figured on net assets instead of expense budgets and only counted admin as overhead, neglecting to add in fundraising expenses. Then, the article went on to list a standard set of figures for a number of entirely different kinds of nonprofits, as if they could be equivalently compared. The newswire I wrote got a lot of readership, and some readers in their feedback wished I had devoted more space to the deep differences between various business models. So, using the same two examples I used in the last newswire (as drawn from the article) and one additional example also drawn from the article, here is a short revisit of why comparing different business models/organizational types makes little sense.

First, I have to make clear that the figures used in the article were accurate to what was published by the Pennsylvania Secretary of State and reprinted in the article. But I have also taken a look at the 990s for all three organizations—and, in one case, an annual report—to get a clearer understanding of their budgets and enterprise types. As is often the case, since one body may ask for different calculations than another, the numbers do not tie out exactly. Even from this slightly incoherent picture, some patterns of enterprise can be discerned.

Three Different Enterprises

The Third Street Alliance for Women and Children provides a combination of community services, including adult day care, early childcare, and shelter. It is likely that the organization includes in its revenue mix contracts and third-party payments, each of which will require reporting, billing, and, in some cases, accreditation. All of this takes management and revenue development. If the article from which we drew this example had computed the ratio properly, the organization would have shown so-called overhead expenses as $357,000 against $1.7 million, or 21 percent.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

- Gross contributions: $658,000

- Net assets: $3.5 million

- Program services expenses: $1.3 million

- Management and general expenses: $302,000

- Fundraising expenses: $65,000

When you look at the proportionate dollars spent on management versus the dollars spent of fundraising, you can infer that this is a direct service agency, likely more dependent on contracts than donations. On the other hand, the United Way of the Greater Lehigh Valley fundraises most or all of its revenues; it looks like this:

- Gross contributions: $11.6 million

- Net assets: $8.8 million

- Program services expenses: $10.3 million

- Management and general expenses: $850,000

- Fundraising expenses: $1.3 million

Here, you have an organization whose overhead ratio looks like it hovers close to 20 percent and, in this case, invests very heartily in fundraising over management- because it is primarily a fundraising body—that is its raison d’être. But, here’s the thing: Much of the money they raise, which ends up in the program services category, must go on to another nonprofit in order to be spent for community benefit, and that means that it will be subject to another layer of administration and fundraising costs.

Both of the previous cases were listed as having less than 10 percent overhead in the article, by the way, because the author figured the ratio by taking just the management and general expenses—without fundraising costs—and figuring that against net assets.

The article also published the numbers for the ARC of Lehigh and Northampton Counties, tagging it with the comment, “The following charities and nonprofits spent the equivalent of more than 10 percent of their total assets on management and general expenses during the most recent fiscal year of data available.” This, too, is technically true but meaningless.

ARCs, of course, serve people with intellectual and developmental disabilities; their programs are generally highly regulated and almost entirely government-funded, and their margins are often razor-thin. (Think of this as the nonprofit equivalent of that low-margin supermarket.) In this case, according to its most recent annual report, it raised $10,839,360 of $11,217,313 from government contracts, which we know rarely pay full costs. Here is what its numbers were in the fiscal year ending on June 30, 2017:

- Gross contributions: $190,000

- Net assets: $6.6 million

- Program services expenses: $10.5 million

- Management and general expenses: $1 million

- Fundraising expenses: $190,000

If you figure the overhead costs of $1.19 million properly against the $11.7 million that constitutes its budget, it is actually much closer to the 10 percent than either of the prior two organizations, and that is not a comfortable position to be in. It means the agency’s budget is probably being supplemented by human capital—or, more prosaically, below-market wages. And, indeed, when you look at the salary of the executive director at this $13 million organization, according to its 2015 Form 990, you can see that it is listed at $102,000, well below what many might expect at an agency this size. In fact, at the similarly sized ARC Broward in Florida, the president is making around $215,000. At the smaller ARC San Francisco, the CEO is making $185.000. So, if anything, this organization is cutting too close to the bone on overhead and is still managing to balance its budget.

Again, I have not gone deeply into the financials of any of these organizations, and so I’ve inevitably missed some important variables specific to the agencies. But, I am writing this to make three points:

- Stories that misunderstand and attempt to simplify beyond reason the basic financial patterns of nonprofits are not only disrespectful but can be harmful to nonprofits. Does the ARC’s board need to worry about being portrayed in the local paper as relative wastrels when that appears to be far from the case? Will this help build their attractiveness to donors, even when they badly need their support?

- Local nonprofits should educate the local media so their stories don’t keep the public forever confused about this sector’s management accomplishments.

- Nonprofits themselves should become geekier and more communicative about the fascinating world of nonprofit business models, so these misunderstood stepchildren of the larger economy can be seen as the stars and models of great management that they very often are.

Finally, I would like to direct readers to articles on our site that eschew the use of so-called “overhead” in favor of more a sensible and practical understanding of your budgets. One of these is “Why Overhead is not the Real Issue.”