Working in FrameWorks’ “metaphor kitchen” on the thorny problem of how to convey the ocean’s centrality to environmental health, a team of smart, seasoned social scientists hit on a candidate metaphor: Our planet is like the Internet. Just as the Internet is composed of interdependent components, so, too, is our planet, and the ocean is one of the planet’s key components. If the ocean is unhealthy, it harms the atmosphere, the climate, and the planet more broadly—it takes them “offline.”

The metaphor of The Planet as Internet seemed promising, since the Internet is something we all experience every day, and the web-like nature of the Internet seemed to accurately illustrate the connections among planetary systems. But what looks good inside the kitchen often fails the taste test on the street.

When this metaphor was beta-tested as a communication tool for members of the public, it failed. In interview after interview, participants showed limited knowledge of how the Internet actually works and, as a result, they struggled to connect the idea of the Internet to the planet and the ocean in particular. From these conversations on the street, it was clear that The Planet as Internet was a no-go.

What can nonprofit communicators learn from this? Nonprofits often must communicate about complex issues, like poverty, climate change, and education, that are systemic in nature and involve many interdependent parts. And because of their complexity, they’re challenging to communicate without “dumbing it down.”

Communicators are often advised to use metaphors to simplify and explain social problems in a way that is familiar to people. Metaphors allow people to think about an abstract idea by integrating it into knowledge they already have about something more concrete.1 When a new concept is compared to a more familiar one, the features that they have in common are highlighted, while their differences are masked.

There is a substantial body of scholarship that attests to this. Metaphors are pervasive not only in language, but also in our minds, as George Lakoff and Mark Johnson persuasively argued in 1980. This idea, often referred to as conceptual metaphor theory, has been substantiated by research in a range of fields, such as linguistics and psychology.

Such work has shown that metaphors structure the way we think about concepts as ubiquitous as time, morality, and power. For instance, not only do we talk about the future as “ahead” of us, but we actually think of the future as ahead of us.2

Engaging in creative metaphor development means not only understanding the metaphors that people are using, but also identifying alternatives and evaluating where those new metaphors take them. Effective metaphors can increase understanding of an issue, garner support for policies, and encourage people to see that social change is possible.

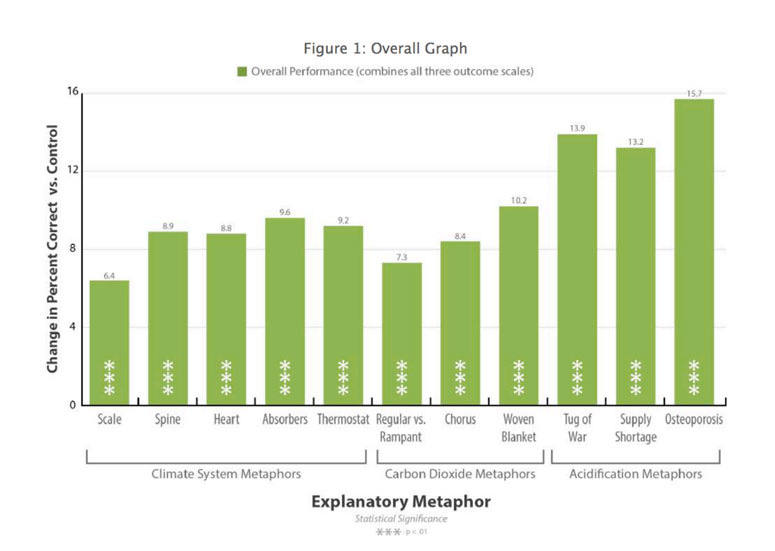

When FrameWorks says a metaphor “works,” it means that the metaphor has, for example, helped people understand why something is a problem and what needs to be done. FrameWorks uses a range of methods to evaluate whether any metaphor accomplishes these tasks, including qualitative analyses and a controlled quantitative experiment. For example, we found that a number of explanatory metaphors increased people’s understanding of the ocean and climate change, as demonstrated by more accurate responses to multiple-choice questions, as shown below.3

On the x-axis, the graph shows the range of different metaphors that were designed to communicate the role of the ocean in the climate system and the harmful effects of excess carbon dioxide for the ocean and climate more broadly. The y-axis shows how much more accurate participants who read one of these metaphors were on questions that probed knowledge about the impacts of carbon dioxide, ocean acidification, and the climate system than participants who did not read an explanatory metaphor. Thus, the graph demonstrates that all of the candidate metaphors boosted understanding of these environmental concepts. It also shows that some metaphors (like “osteoporosis of the sea”) were more successful than others. Collectively, though, we see that a number of different metaphors can be used to broaden understanding.

On the x-axis, the graph shows the range of different metaphors that were designed to communicate the role of the ocean in the climate system and the harmful effects of excess carbon dioxide for the ocean and climate more broadly. The y-axis shows how much more accurate participants who read one of these metaphors were on questions that probed knowledge about the impacts of carbon dioxide, ocean acidification, and the climate system than participants who did not read an explanatory metaphor. Thus, the graph demonstrates that all of the candidate metaphors boosted understanding of these environmental concepts. It also shows that some metaphors (like “osteoporosis of the sea”) were more successful than others. Collectively, though, we see that a number of different metaphors can be used to broaden understanding.

Since its inception, FrameWorks has embraced metaphors as powerful explanatory tools, with an important caveat: Not all metaphors are created equal. This should serve as an important caution. The wrong metaphor can backfire. You may not have the opportunity to test your new metaphor on the streets, as we did with the Planet as Internet idea, but there are evidence-based best practices you can leverage when designing metaphors for social change.

Use a relatable concept when describing a more complex, abstract idea—but carefully test your preconceived ideas of what people know.

Good metaphors are inherently democratizing: they rely on objects and actions that are familiar to everyone. This way, people can use their knowledge of the well-known concept to make sense of the less familiar one. It’s important to note, however, that it’s challenging to always know which topics are familiar to people and which aren’t. (Recall the Planet as Internet example, which taught the FrameWorks researchers that even though the Internet is ubiquitous in our daily lives, it is not necessarily something people truly understand.)

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Here is another precautionary tale from FrameWorks’ experience: When designing frames for communicating about education, FrameWorks research yielded a useful familiar explanatory metaphor for overcoming the narrow perception that teachers, parents, and students were the only players in educational outcomes. The educational orchestra contains many players with different jobs who must work together for the best outcomes.

Ironically, we had pushback from some partners about whether an orchestra really was familiar, or whether it was too elite to serve as a conceptual foundation for many people. It turns out that most Americans have robust understandings, rich in imagery, of orchestras, and many of these concepts promote useful ideas of practice, harmony, synchronization, and teamwork. So, finding out what really is familiar, rather than what appears to be a common concept, is worth the extra effort.

Use metaphors that convey new ideas.

Metaphors that are somewhat surprising lead people to pause and think more deeply about an issue than canned phrases or tired clichés. Our brains actually have to exert more effort to understand novel, unconventional metaphors than otherwise similar conventional metaphors.4

For example, talking about children as being “shaped” or “molded” by parents and teachers is so commonplace that this metaphor hardly even strikes us as metaphorical at all. As a result, it doesn’t lead to new insights for thinking about what children need for healthy development.

By contrast, FrameWorks research has repeatedly demonstrated that the more novel metaphor of “brain architecture”5 (the structure of a child’s brain, which needs to be built sequentially, starting early in life) is more informative and conducive to thinking about key ideas from the science of child development.6 Brain architecture is a more novel way of talking about development. Novelty is surprising, and this surprise factor encourages people to reconsider their current way of thinking about child development.

Use metaphors that shine light on solutions, not those that solely depict a problem.

The best metaphors help people think productively about ways to address a problem; otherwise, they are likely to leave people thinking that the issue is inevitable and unsolvable, even though they may understand the problem better.

For example, carbon emissions are frequently referred to as greenhouse gases. But when FrameWorks conducted research on climate change in the US and Canada, it quickly became apparent that not only are people unfamiliar with how greenhouses actually work, but the metaphor also fails to shed light on whether solutions are needed, and if so, what those solutions might be. After all, aren’t greenhouses good things that allow plants to flourish? By this reasoning, not only are solutions invisible, but they actually seem unnecessary. For this reason, the greenhouse gases metaphor backfires, as it is counterproductive for thinking about effective responses to climate change.

By contrast, FrameWorks research shows that talking about carbon emissions as contributing to a heat-trapping blanket is more effective: We are all familiar with blankets, and when they trap too much heat, we know to toss the blanket off. This understanding that humans can act to stop the heat-trapping blanket makes it easier to see that we can also act to reduce climate change—specifically, we can reduce carbon emissions.7

Keep it simple.

One of the greatest advantages of metaphors is that they can be shared orally. For this reason, they should be succinct and easy to pass from one person to others. It may be tempting to craft a complicated metaphor, one that needs to be explained in detail for people to fully grasp it. But long and convoluted metaphors are hard to remember and are therefore hard to pass on. If metaphors aren’t passed on, from neighbor to co-worker, they can’t contribute to the long-term social change they were designed for. When FrameWorks tests metaphors, we play a game of “telephone,” where we teach a metaphor to a pair of research participants and then ask them to teach it to another pair, and they explain it to another pair, and so on. Researchers watch how well the metaphor holds up, especially when it is “dropped” along the way—the best metaphors “bounce back,” as people can use their own knowledge of something to fill in the missing information.

One of our favorite examples of a concise and “sticky” metaphor likens young children’s executive function skills to air traffic control at a busy airport.8 Like air traffic control, executive function skills regulate the flow of information and the focus on tasks, create priorities, and keep the system flexible and on time. This metaphor works because it’s concise and easy to visualize, which in turn make it easier to pass on.

Metaphors are powerful tools for communicating about complex and abstract ideas. They set forth new ways of talking about concepts that in turn set forth new ways of thinking. Metaphors can shine light, open doors, and elevate ideas in ways that can help the nonprofit sector change the conversation about social issues, a critical step toward creating lasting social change.

As researchers, we believe the best metaphors are those that have been tested. But even if you don’t have the benefit of our metaphor kitchen, you can avoid the Planet as Internet problem by trying out your ideas at the water cooler, over coffee and in social conversations with as many people from disparate backgrounds as possible. When you see the metaphor being picked up and used again and again, and when it helps people see the kinds of solutions you hope to promote, then you are on to something.

Notes

- Thibodeau, P.H., Hendricks, R.K., & Boroditsky, L. (2017). “How Linguistic Metaphor Scaffolds Reasoning.” Trends in Cognitive Sciences. Thibodeau, P.H. & Boroditsky, L. (2011). “Metaphors We Think With: The role of metaphor in reasoning.” PLoS ONE.

- g., Rinaldi, L., Locati, F., Parolin, L., Bernardi, N. F., & Girelli, L. (2016). “Walking on a mental time line: Temporal processing affects step movements along the sagittal space.” Cortex, 78, 170–173.

- Getting to the Heart of the Matter: Using Metaphorical and Causal Explanation to Increase Public Understanding of Climate and Ocean Change.

- Lai, V.T., Curran, T., & Menn, L. (2009). “Comprehending conventional and novel metaphors: An ERP study.” Brain Research, 1284, 145-155.

- Talking Early Child Development and Exploring the Consequences of Frame Choices: A FrameWorks Message Memo.

- Framing Early Child Development: Message Brief.

- How to Talk about Climate Change and the Ocean: A FrameWorks Message Memo.

- Air Traffic Control for Your Brain: Translating the Science of Executive Function Using a Simplifying Model.