“More than 150,000 Floridians had their voting rights restored during former Gov. Charlie Crist’s four years in office. In the seven years since then, current Gov. Rick Scott has approved restoring voting rights to just over 3,000 people,” notes Greg Allen for NPR.

Allen adds, “Across the US, most states restore voting rights to felons after they’ve completed their sentences. Some wait for probation and parole to be complete.” For a brief period under former governor Charlie Christ, this was true in Florida too. Current governor Rick Scott rolled back those laws, and Florida felons can forfeit their right to vote in perpetuity.

Universal suffrage, it should be noted, is widely seen as the minimal condition necessary for democracy. A few years ago, Arend Lijphart, former president of the American Political Science Association and a leading international scholar of democratic institutions, observed,

We need to establish a threshold below which a country cannot be regarded as democratic. For instance, an essential condition for democracy—a necessary, although obviously not sufficient condition—is universal suffrage. This basic fact is often disregarded, for instance, when in his 1993 inaugural address, President Bill Clinton called the United States “the world’s oldest democracy,” although universal suffrage was not firmly established until the passage of the Voting Rights Act in 1965.

Lijphart adds that in his own earlier work, “I must confess to having been rather lenient, and perhaps too lenient,” in labeling the United States as a stable democracy from 1945 on, given that “many blacks in pre-1965 America did not have the right to vote.”

Even after the Voting Rights Act finally allowed for near-universal adult suffrage to take hold in the US, there was an exception—states can still deny the right to vote to those convicted of felony, even after their release.

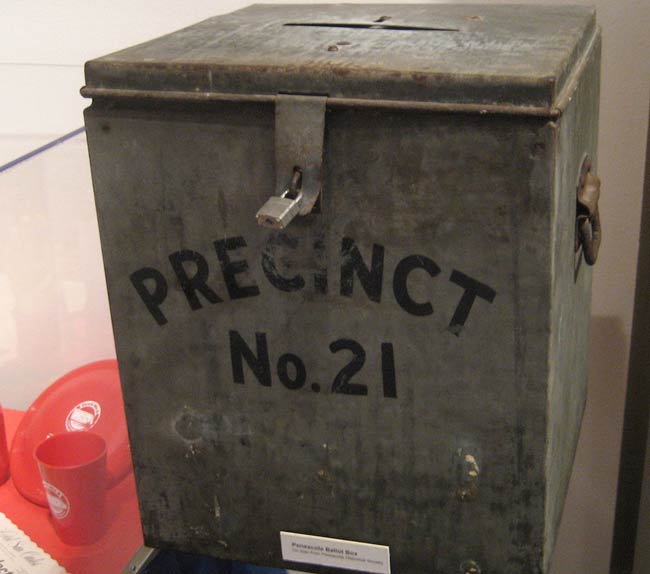

As Allen explains, “In Florida, more than 10 percent of the adult population is prohibited from voting because they’ve had felony convictions. Under a law that dates back to the Reconstruction era, Florida bars felons from voting, unless officials approve a request to have those rights restored. That means nearly 1.5 million people in Florida can’t vote, even though their sentences are complete.”

Other states in the South with similar rules are Alabama, Mississippi, Tennessee, and Kentucky. Five states outside the South offer similar restrictions: Delaware, Wyoming, Iowa, Nevada, and Arizona.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

It is notable that of 44 surveyed countries outside the US, only three—Armenia, Belgium, and Chile—ban post-release voting by felons. By contrast, nearly half (21 of 44), including Canada and Germany, guarantee the right to vote in prison (a practice also adopted by two US states—Maine and Vermont).

Of course, disenfranchisement follows racial lines. In Florida, Erika Wood, a former law professor, notes, “Nearly one-third of those who have lost the right to vote for life in Florida are Black, although African Americans make up just 16 percent of the state’s population. Florida’s law disenfranchises 21 percent of its total African American voting-age population.”

Conor Friedersdorf of the Atlantic adds, “Disenfranchisement echoes across communities and generations: Some eligible voters are less likely to vote when their friends and neighbors are staying home; children who never see their parents vote grow[ing] up are less likely to cast ballots themselves.”

Meanwhile, for former Florida felons seeking voting rights, a strange charade plays out. Allen writes: “In Tallahassee, four times a year, dozens of anxious people gather to hear a decision that will affect the rest of their lives. Felons whose sentences and probation are complete stand before the governor and other Cabinet members to ask for clemency and the restoration of their right to vote.”

Most requests are denied. At a 2016 hearing, Allen reports Scott’s attempt to explain to one man why he was denying his request to have his rights restored.

“Clemency is—there’s no standard. We can do whatever we want,” said Scott. “But it’s…tied to remorse. And…understanding that we all want to live in a law-abiding society.”

Jon Sherman of the Fair Elections Legal Network represents ex-felons who are suing the state. One plaintiff, Allen says, “is Yraida Guanipa. She served 11 years on a drug trafficking conviction before being released in 2007. Since then, she’s gone back to college, earned a bachelor’s and a master’s degree, and started a business in Miami. Her probation ended in 2012, but Florida’s law requires her to wait an additional seven years before applying to have her rights restored.”

“The seven years is not up until next year,” Guanipa says. “And after that, I have to get into the line of the backlog, of maybe 10 years. I probably would be dead.”

Another group, the , has qualified a constitutional amendment for the November ballot that would enable former felons to vote. Polls show two-thirds in favor, but passage will require at least 60 percent “yes” votes on election day.—Steve Dubb