This article is from the Nonprofit Quarterly’s winter 2015 edition, “When the Show Must Go On: Nonprofits & Adversity.” It was first published online on January 25, 2016.

Big strides have been made recently in the acknowledgment that overhead ratios are poor indicators of an organization’s impact or financial efficiency. Although the movement toward outcomes-based measurement offers a promising alternative to understanding impact, very little has been done to truly shift the sector’s understanding of what it takes—or even means—for nonprofits to be financially efficient and adaptable. The myths and misinterpretations of the true full costs of delivering vital programs have contributed to a chronically fragile social infrastructure for our communities.

Now more than ever, as the call to achieve high standards of outcomes-based measurement grows, we must hold ourselves to an equally high standard of understanding nonprofits’ full costs. This article is meant to encourage nonprofit executives and boards to know and advocate for their full costs, and to urge the philanthropic sector to structure funding with greater consideration for the full context in which its grantees are operating. We look forward to the day when nonprofits and funders have embraced the concept of full costs, which include far more than direct program expenses and so-called “overhead.”

Overhead as a Parental Control

Many foundation leaders now understand that overhead is part of the real, necessary costs of delivering quality programs. Funders large and small have shifted grant strategies to fund overhead. In 2013, Charity Navigator, GuideStar, and the BBB Wise Giving Alliance spoke out against the myth that overhead spending is a meaningful way to evaluate nonprofit performance.1 Even the federal government, at the end of 2014, began requiring federal grants to cover nonprofit overhead costs.

Yet, it seems practice is lagging behind public discourse: In Nonprofit Finance Fund’s Annual State of the Nonprofit Sector Survey 2015, only 7 percent of nonprofits report that foundations always cover the full cost of the projects they fund; while decrying the overhead ratio as a “poor measure of a charity’s performance,” Charity Navigator still includes the overhead ratio as the very first financial performance metric in its evaluation; and the federal government set a pitifully low default overhead reimbursement rate of 10 percent. In other words, funders and watchdogs (and probably even nonprofits themselves) are not “there” yet in recasting overhead as an essential cost of providing services—and we have farther to go than you might think.

Imagine if your personal paycheck were like a restricted grant. Instead of representing your value and level of responsibility in the company, your paycheck is based on a predetermined line-item budget that details exactly how you can spend your earnings. A portion of your paycheck can be used for rent, some for utilities, but most is earmarked for business attire, transportation to work, and coffee to keep you productive throughout the day. The thinking here is that by tying your paycheck to the expenses that contribute to your work, the company is making sure that you will show up on time, appropriately caffeinated, and properly dressed. It’s as if every penny of your paycheck is spent before you cash it.

To some extent, you had a say in your paycheck budget. In fact, you had to present a proposed paycheck budget when you applied for the job. Your friends on the inside said no one who spends more than 20 percent of his or her paycheck on rent has ever been hired. To get the job, you cut your rent line item. That means making do with an efficiency unit above an all-night bowling alley, but it’s better than not having a job at all. Some line items were nonnegotiable from the start: As a policy, your company won’t pay for haircuts; but that’s okay—you can let your hair grow long.

At the end of the year, the company assesses your job performance by comparing your actual spending to the line-item budget. Your spending is carefully scrutinized for fluctuations of 10 percent or more, and your job is in jeopardy if it fluctuates too much. You know this measuring of line-item expenses doesn’t say much about the value you created for the company. You are pretty certain you would be more productive if you could just get a good night’s sleep, but that would mean moving away from the bowling alley, and that would put you over budget and in danger of being fired.

The company doesn’t feel great about measuring your line-item expenses either. They know it’s not a great proxy for your productivity, and the truth is they actually want to pay you based on a true measure of value. Unfortunately, they just aren’t sure how valuable you are. They’ve asked you for the data, but you don’t have a system to track it—not to mention, you tend to show up to work a little worse for the wear. You always seem tired and your hair looks rather unkempt. (Don’t you know someone who will cut your hair for free? The other employees do.)

If we start to fully fund nonprofits for their day-to-day program and overhead expenses, and abandon overhead measurements as a proxy for mission fulfillment and efficiency, it’s the equivalent of giving nonprofits control over their paycheck. With the flexibility to manage their own funds they can make better spending decisions—like moving away from the bowling alley, not spending so much on business attire, and finally getting a haircut. Despite the fact that they are spending less on items that “directly support the work” (business attire, coffee) and more on “overhead” (rent, haircuts), the nonprofits can make smarter spending decisions that actually let them produce more value. Without a doubt, this arrangement would be a huge improvement over the status quo.

This is where the conversation has generally stopped—as if we had reached the answer: When nonprofits are able to cover their overhead with flexible funding, they do better work for communities; fund overhead, and we will have the healthy, resilient nonprofit sector we need to make real social change. But in our paycheck example, recall that every month, you spend your entire paycheck down to the penny. After you pay all your expenses—including rent for your new apartment and your monthly haircut—your bank account balance is $0. You set aside nothing for emergencies, nothing for retirement, nothing to replace your aging car in a few years. You have no savings. You have no safety net.

Herein lies the danger of the focus on funding overhead: we may think we’ve arrived once nonprofits “gain control of their paycheck,” and forget that resilient nonprofits need a safety net. Nonprofits need to be paid for their full costs.

What Will We Gain When We Stop Talking about Overhead?

This article will never provide a clear definition of overhead. Unfortunately, we can’t. While overhead is most commonly thought of as the expenses presented as management and general and fundraising functions on Form 990s or audited financial statements, the accounting guidance to determine which expenses belong to which function is so vague that reasonable people make wildly different determinations about how to allocate expenses across functions. What ends up classified as overhead is so open to interpretation, even manipulation, that we cannot provide a useful or consistent definition.

McGroarty Arts Center, where I was executive director from 2005 to 2013, provides an excellent example of just how difficult it is to determine which costs are overhead and which are program. Ceramics students at the small Los Angeles center wanted to raise money for new studio equipment. They created the Annual Ceramics Exhibition and Benefit—a volunteer-driven fundraiser that exhibits curated work of emerging ceramic artists. Is the event a fundraising expense? In some years, the Annual Ceramics Exhibition and Benefit barely breaks even—but the event is so highly mission-aligned and impactful that the center was committed to the event whether or not it made money. So is it a program expense? As the event grew in popularity and artistic reputation, the staff devised ways to capitalize on its momentum. Guided gallery tours are arranged for local schools and senior centers, and private receptions are held in the evening for the organization’s most important donors. Fundraising expense?

The accounting guidance does not tell us how to allocate the Annual Ceramics Exhibition and Benefit expenses across functions. The art center struggled to present the event expenses accurately, treating it as a fundraising expense in some years, a program expense in others. Some years, the art center came up with complicated rationales for allocating a portion of expenses across functions. Each year, the center consulted with tax accountants and auditors. Each year, it was told that its allocation was reasonable. The center would have been better served to allocate the entire event to programs and use its limited staff time on something beneficial to the organization. But the center’s leaders desperately wanted to be truthful and abide by the rules.

Nonprofits spend far too many resources attempting to report their functional expenses honestly. Costly time studies and complicated time sheets are used to determine how many hours each staff member spends on programs. Organizations build and maintain complicated accounting structures so every expense can be reported by function. A simple phone bill is recorded in the books as a lengthy journal entry of functional allocations, with back-up detail for the auditor to test at the end of the year. To what end?

The reporting of functional expenses exacerbates the myth that, somehow, nonprofits should be able to operate programs without an administrative structure to manage, measure, and execute. It implies that, by some as-yet-unknown magic, nonprofits should be able to achieve their mission without dedicated and systematic fundraising efforts to pay for it. The attempt to segregate interwoven and complementary expenses according to the function they serve is an exercise in futility. The truth is, all resources spent by a nonprofit are spent in order to successfully deliver on programs (with obvious exceptions made in cases of fraud). Certainly, not all spending in a nonprofit is efficient; but functional expenses tell us nothing about efficiency.

By abandoning overhead, we free up limited nonprofit capacity to focus on more important measures. With the coming sector-wide shift toward outcomes-based measurement, this capacity is needed now more than ever.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Why We Can’t Live above the Bowling Alley Anymore

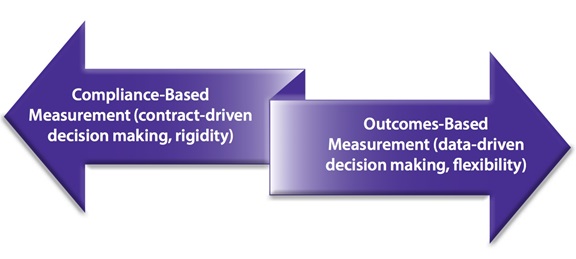

Remember when you couldn’t control your paycheck, so you lived above the bowling alley? It wasn’t ideal, but your housing choice allowed you to keep your job. Yes, you were always tired, and that meant you weren’t as effective in your work as you could have been, but you weren’t measured on your productivity; you were measured on compliance. But what if you were measured on both compliance and productivity? What would you have done? The two measurement standards are at odds with each other. You won’t be in compliance with your paycheck line-item budget if you move away from the bowling alley. But you certainly won’t meet your productivity measures if you can’t sleep well at night. This impossible future is looming for nonprofits—if we don’t head it off first.

As the sector moves toward outcomes-based measurement, we have to move away from compliance measures like overhead ratios and restricted budgets. The nonprofit sector can’t “live above the bowling alley” and be expected to achieve results for its communities. To meet outcomes, organizations must be flexible and make a healthy investment of funds and staff capacity in the systems that allow organizations to track their impact over time. Outcomes-driven decision making requires organizations to pivot and shift quickly as the environment around them moves or as new information becomes available; compliance-driven decision making requires adherence to rigid rules, even in the face of changing needs. The two are incompatible.

More and more funders are expecting the programs they fund to deliver measurable change or impact. The cost associated with developing, testing, maintaining, and, ultimately, reporting outcomes is terribly expensive, and usually underestimated. When you gained control of your paycheck, you were able to make fluid and smart decisions—like moving away from the bowling alley—without worrying about a poor performance review. Let’s be sure nonprofits can do the same.

Full Costs: A Focus on Mission and Outcomes

We’ve been so distracted by the discussion of whether nonprofits should just be able to pay their day-to-day operating expenses (and how)—including overhead—that we’ve mostly ignored the need for nonprofits to generate enough surplus to reinvest in the organization’s immediate and future health. After revenues are used to pay day-to-day operating expenses, surpluses should pay for:

- Cash to meet liquidity needs like paying bills on time (working capital);

- Cash or liquid investments to protect against reasonable risks and take advantage of new opportunities (reserves);

- New furniture, equipment, or buildings (fixed asset additions); and

- Debt principal repayment.

Full costs include day-to-day operating expenses (both program and overhead expenses) plus a range of balance sheet costs for short-term and long-term needs. Let’s use this formula to think about full costs:

Day-to-day operating expenses + working capital + reserves + fixed asset additions + debt principal repayment = full costs

Paying nonprofits their full costs is how we prevent crises and interrupted services for communities and allow leadership to stay focused on mission and outcomes. Anyone who has worked in a cash-constrained nonprofit knows that when a cash-flow crisis hits, mission stops, strategy stops, and all the energies of management and board are diverted to moving up receivables, delaying payables, and securing cash however they can. Appropriate working capital prevents program disruption due to cash flow shortfalls.

Revenue streams in the nonprofit sector can be unpredictable, even fickle. An organization should not have to pass up an amazing opening to move its mission forward because it can’t secure the upfront cash quickly enough. The loss of a major funder should not trigger the immediate, irresponsible shutdown of essential programs. Appropriate reserves allow organizations to respond to opportunities and risks in a strategic and thoughtful way that protects their communities and moves their mission forward. (For any funders worried about an organization becoming dependent on your support, think about whether it has the reserves to reposition itself in the absence of your funding.)

An organization with aging technology loses valuable staff time—and sometimes irreplaceable data—struggling with frustrating work-arounds and inefficiencies. A facility-owning organization with a plumbing emergency will experience significant staff distraction and may have to temporarily suspend activity while the cash can be found to hire the plumbers to make the repairs. It’s a safe bet that when the toilets aren’t working, neither are the programs.

Used wisely, debt can help an organization fund a capital project or bridge receivables. An organization that falls behind on debt repayment will distract leadership from mission and will struggle to advance its work in the community. An organization can even fold under the weight of its debt, leaving communities without services. Without full cost funding to cover debt principal repayment, an organization cannot keep a long-term commitment to the people it serves.

Communities pay the price when full costs are not met.

The “Doom Loop” of Underfunded Full Costs

Why have so few nonprofits and funders been talking about full costs? Perhaps because many don’t know the price tag for their own or their grantees’ full costs.

Nonprofit financial capacity—staff time, expertise, and systems—is extremely limited. Overly burdensome reporting requirements use up limited nonprofit financial capacity to manage compliance vis-à-vis: the specific line items the funder requests in the budget; splitting up phone bills according to the amount of time fundraising staff are thought to have spent on calls; checking and rechecking invoices to government funders that will be rejected if they contain even a one dollar rounding error. Nonprofits barely have the bandwidth to manage financial compliance, let alone foresighted financial management issues like full cost. And who can blame them? The stakes are high. A compliance error can mean delayed payments or rejected grants. That means people don’t get paid. That means communities don’t get served.

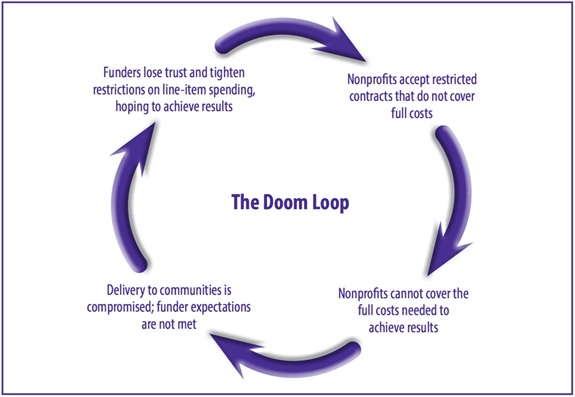

Existing dynamics in our sector actually discourage transparent reporting of full costs. When it comes to competitive contracting, nonprofits fear they will not be selected for funding if they reveal how expensive it truly is to deliver their intervention, and as a result shy away from asking for full costs. Grants and contracts frequently lock organizations into budgets that were built months or years ago, often with little or no wiggle room to adjust to new opportunities or more efficient ways of operating. The time, energy, and reputation risk to apply for a budget modification isn’t worth it. Claw-back clauses, which prohibit organizations from generating surpluses that contribute to balance sheet needs, are common and often accompanied by explicit refusal to pay for budget overruns. Nonprofits can’t set aside savings in case of budget overruns, but no one else will pay for them, either. Nonprofits can’t win. Dynamics like these mean that only the luckiest organizations cover their day-to-day operating expenses, and all organizations are denied the opportunity to safeguard their communities by paying for balance-sheet needs. They are incentivized to report costs in such a way as to maximize short-term resources for their community, and not in a way that maximizes transparency and feeds longer-term sustainability for the service provider.

The failure to fund full costs has resulted in a cycle of distrust between nonprofits and funders and, ultimately, puts at risk program delivery to communities: The “Doom Loop” of underfunded full costs.

Four Things Nonprofits can Do Right Now

- Know your full costs. Set aside some of your limited time to analyze your true costs of operating. Throw compliance out the window for this exercise, and think through the operating realities of your organization. What are your day-to-day expenses? How much cash do you need in the bank at the worst times of the year to pay your bills on time? What funds should you have that can be set aside to maintain your facility, upgrade your technology, or invest in new systems? What risks do you see coming down the road, and what would it take to meet those risks? What opportunities should you take, and how much money would you need to take them? Do you have any debt to repay, and what is your plan for repayment?

- Ask for your full costs. Update your communication and your fundraising pitches to reflect what it truly costs to deliver your interventions and sustain your work over the long term. Change doesn’t come cheap. Don’t undercut your mission and put your community at risk by asking for less and promising more. Think carefully before accepting contracts with unfunded mandates—those that do not fully pay for themselves. Consider whether adequate flexible funding from other sources will be available to fill in the gap. Avoid borrowing from the future.

- Banish the overhead ratio. Don’t use low overhead as a fundraising tool (i.e., no more pitches that $0.90 of every $1.00 is spent directly on programs). Don’t use it as a management tool. Don’t use it as a proxy for efficiency or effectiveness.

- Practice new ways to talk about overhead. The reality is, most overhead costs are people costs—educated employees who contribute to mission by making sure the organization runs smoothly. Talk about what they do in compelling, specific detail, and how it contributes to mission: “Our counselors do their best work with survivors of domestic violence when they can give each client their full time and attention. That’s why the work of our professional HR team is so important. By attracting and retaining effective staff members, ensuring payroll is accurate and on time, managing benefits, and handling proof of counselor qualifications and required training, our HR team lets counselors spend more time with our clients. This results in more clients served and stronger relationships between clients and counselors.”

Four Things Foundations Can Do Right Now

- Pay for full costs. Even if you do not provide general operating grants, it is important to recognize that programs draw their fair share of organizational infrastructure. Be sure to fully pay for the costs your grant may impose on nonprofits—including data collection and reporting, convenings and trainings, and a reasonable surplus for liquidity and to address the unexpected. Include a line item in your grant budgets for indirect costs—those costs that are necessary to running the organization and the program but don’t increase or decrease in direct relation to the program. Allow grantees to tell you what a reasonable indirect cost is for their organizations; don’t prescribe a set percentage.

- Create a safe space for nonprofits to ask for their full costs. You probably have grantees who don’t really know their full costs. Nonprofits have a history of underpricing their programs. When they truly unpack the full costs of delivering on mission, they may hesitate to share the information with you for fear of sending you into sticker shock. Communicate openly with your grantees. Give them the opportunity to reset their costs of doing business in the full-cost mindset without losing funding or being perceived as greedy or disingenuous. Provide cover for those nonprofits that are ready to reexamine cost. Publicly announce that your foundation seeks requests that articulate full costs. Open a dialogue if nonprofits come to you with a low number, and make sure they are not undercutting themselves for fear they will not be funded if their overhead is too high. One conversation is not enough. Continue to reinforce the importance of full costs.

- Banish the overhead ratio. Do not include the overhead ratio in your grantmaking decisions or due diligence process.

- Directly support full costs through flexible funding or enterprise-level support. Remove claw-back clauses from your contracting, and allow nonprofits to keep unspent funds as general operating support. Instead of restricting dollar inputs, measure what the organization achieved by spending grant funds. Provide unrestricted general operating support that allows nonprofits to cover their full costs.

Note

- Charity Navigator, GuideStar, and the BBB Wise Giving Alliance, “The Overhead Myth: Moving toward an Overhead Solution,” 2013, Open Letter.

Nonprofit Finance Fund thanks the Weingart Foundation and the California Association of Nonprofits for their assistance with this article. For additional information, see the Nonprofit Overhead Project.