For over 20 years, I have explored how to change financial systems in the United States to promote greater equity and inclusion. This has led me to the conclusion that if we want to close the racial wealth gap, we need to get serious about public banking.

Public banks, owned by state and local governments, are driven by a community-serving mission, Currently, financial systems favor White-owned firms and disfavor firms that are owned by people of color, limiting the wealth-building opportunities available to them. Public banking could help change these dynamics.

Why a Banker Became a Public Banking Advocate

If we want to close the racial wealth gap, we need to get serious about public banking.

How did I come to adopt this position? If you had asked me 20 years ago about public finance, I doubt I could have told you what a public bank was. My journey began far from the financial world. Eventually, I moved from the nonprofit sector to corporate America, working with business leaders who wanted to be more inclusive, and started a business accelerator helping over 30 Black entrepreneurs start businesses, many of which are still thriving over a decade later.

Working with private business, I decided to follow the power and money, and started a consultancy working with financial institutions to change systems within banking. After working with many banks over the years, Berkshire Bank brought me into the bank as a C-suite executive and regional president. This experience helped shape how I understand our economy and why it’s so important for the mainstream banking industry to flow more responsible capital to people of color.

How Finance Currently Reproduces the Racial Wealth Gap

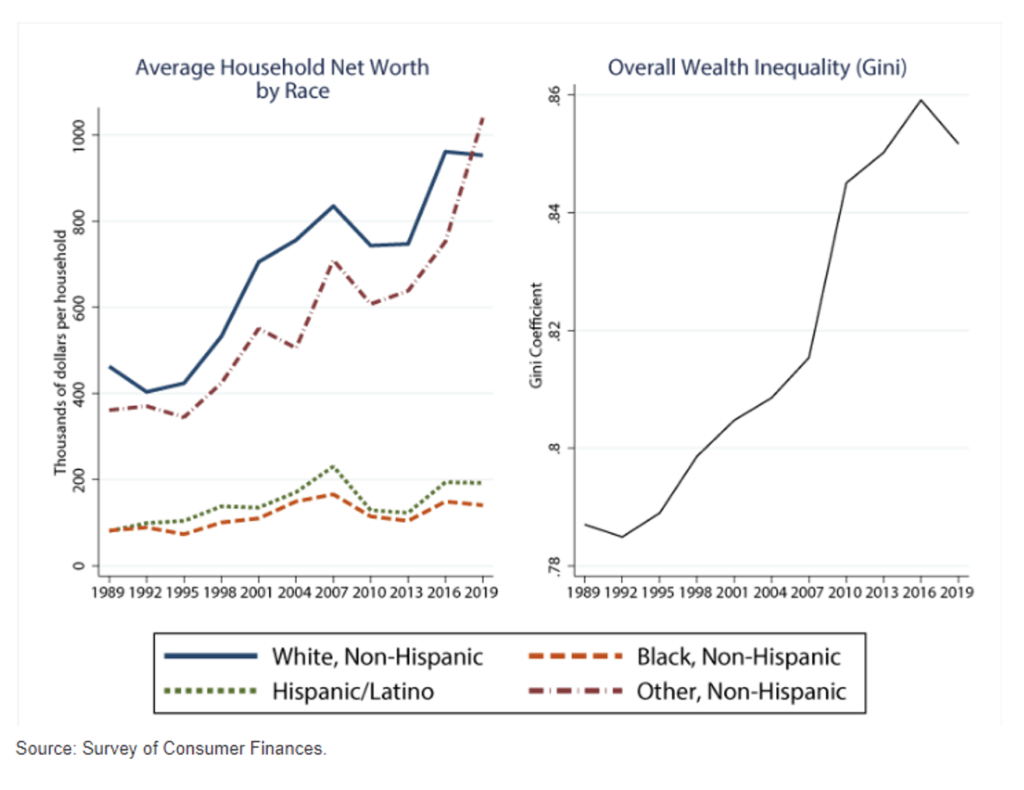

The racial wealth gap is as entrenched as ever—a chasm of earnings power, savings, and investment that threatens to leave behind another generation of Black and Latinx households. According to an analysis by the Federal Reserve’s Board of Governors staff, the average household of color earns about half as much as the average White household and holds only about 15 to 20 percent as much net wealth. An index known as the Gini coefficient—ranging from 0 (representing perfect equality) to 1 (total inequality)—shows a stark contrast.

Over the past few decades, the Gini reading of wealth inequality in the United States has risen from below 0.8 in the late 1980s and early 1990s to 0.85 in 2019, as shown in the graphs below.

In the 2019 Survey of Consumer Finances, the White population in the United States accounted for only 68.1 percent of total households but held 86.8 percent of overall wealth. Black and Latinx households accounted for 15.6 percent and 10.9 percent of the US population but held a disproportionately low fraction of the wealth: only 2.9 percent and 2.8 percent, respectively. “Under racial equality,” the Federal Reserve report states, “Black households would hold over five times the amount of wealth they currently do, and Hispanic households would hold nearly four times as much.”

Ultimately, the wealth gap is about ownership, specifically who gets to own what.Scrutiny of who holds wealth and why has intensified since the Great Recession, when terms like the privileged one percent and the bottom 99 percent became popular nomenclature. With the COVID-19 pandemic, the wealth gap deepened, exposing the harm caused to minority-owned business enterprises (MBEs) and households of color.

As Sylvia Chi and Sushil Jacob observed in NPQ in 2020, federal policy exacerbated the nation’s “existing racial caste system, pushing Black and Latinx business owners to the back of the line.” The Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) awarded billions of dollars to the nation’s largest banks instead of protecting the most vulnerable small businesses. That dismal track record raised the ire of the US Small Business Administration’s inspector general, who condemned the agency’s failure to prioritize rural and underserved markets as the PPP program was rolled out.

Today, the persistence of the racial wealth gap points to an obvious conclusion: the status quo in banking and financial services falls far short of what is needed to move toward financial equality. Ultimately, the wealth gap is about ownership, specifically who gets to own what—and at what price to finance that ownership. The consistent bias in commercial banks limits who can access capital, which makes closing the wealth gap nearly impossible.

Making matters worse, the banking sector has been consolidating through mergers, from over 10,000 banks in 1990 to about 4,000 today. The six largest—JPMorgan Chase, Bank of America, Citigroup, Wells Fargo, Goldman Sachs, and Morgan Stanley—control more assets than all the others combined. If that sounds like less competition and more concentrated control of capital flows, you’re right.

As Shahid Naeem, a policy analyst at the American Economic Liberties Project, wrote in a recent opinion piece for The Hill: “Merged banks also use their market power to pay lower interest rates on deposits and charge consumers and small businesses higher interest rates on mortgages and commercial loans—not to mention the devastating effects of merger-induced branch closures and job cuts on American communities.”

Despite their best intentions, minority deposit institutions (MDIs) and community development financial institutions (CDFIs), like other small banks, simply lack the capital base to close the racial gap. While these institutions are important within a diverse ecosystem, they cannot go it alone.

Enter Public Banks

As a former bank executive, who continues to work with some of the largest financial institutions, I can attest that public banks can be powerful tools of economic uplift.

Public banks are owned by the government—typically municipal and state authorities or other public actors—with a mandate to promote public policy goals that match community needs. As enterprises under government control, public banks provide banking services to state and local governments and finance credit programs to assist those who suffer the most harm from natural or human-made disasters.

Public banks are not a new concept. In fact, they date back centuries and became more numerous during the Industrial Revolution of the late 1800s. In 1836, Congress did not renew the Second Bank of the United States charter, and states were allowed to start their own banks. Banks wholly owned by state governments were established in Alabama, Kentucky, Illinois, Vermont, Georgia, Tennessee, and South Carolina. State governments held a majority interest in banks in Missouri, Indiana, and Virginia, and owned minority interests in banks in other states. These are no longer in existence, supplanted by the rise of national banking, and, ultimately, the creation of the Federal Reserve in 1913.

But there is one notable exception to this trend. In 1919, to support its agrarian economy, the socialist Nonpartisan League (which had won control of the state legislature) established the Bank of North Dakota. The success of its mandate can be found in more recent history. As the Public Banking Institute has noted:

By early 2009, following the banking crisis of 2008, North Dakota was…the only state sporting a major budget surplus. It had the lowest unemployment, foreclosure, and default rates in the country. It also had the most community banks per capita, confirming that the presence of a state-owned bank has helped rather than hurt its local banking sector.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

This latter point cannot be emphasized enough. Public banks are good for the local economy and the financial sector. The Bank of North Dakota itself touts many economic benefits stemming from its lending, including financing economic development, returning surpluses to the state treasury, serving as a resource for the local banking sector, supporting loans to reduce the cost of homeownership and college education, and providing financing for infrastructure and disaster relief.

How does the public bank in North Dakota accomplish these results? One key strategy behind its ability to preserve small banks is what is known in the field as co-participation. Effectively, this means that if a local bank is too small to make a priority community loan, the public bank can step in and support the small bank by effectively providing a “match” to the small bank’s loan. This strategy increases capital for the local community economy, democratizes banking, and allows smaller banks to grow sustainably rather than get swallowed up by larger banks, as has been the national trend for decades.

Communities benefit in turn, since they get the closer attention that a small community bank provides while also enjoying access to the larger pool of capital made available by the state-backed public bank. The combination of local knowledge and statewide capital is powerful.

As Christie Obenauer, CEO of Union State Bank, which operates three branches in rural North Dakota, explains, the public bank functions as an “extension of who we already are. I’m only a $150 million bank” in an industry where any bank with less than $10 billion in assets is considered small and in which the four leading banks have over $1 trillion in assets.

“The Bank of North Dakota allows us to be bigger than we are,” Obenauer continues, “they just allow us to do big things, even if we’re small.”

The Push for Public Banks

Today, more public banks are being launched and planned. For example, Public Bank Los Angeles (PBLA) was established as a socially and environmentally responsible municipal bank for the City of Los Angeles. PBLA also helped pass AB 1177, the California Public Banking Option Act, known as CalAccount, under which free and penalty-free debit cards will be offered to all Californians, providing basic financial services such as check cashing, deposits, and bill paying.

PBLA states that its goal is “to provide affordable financial services and promote economic growth in California by providing greater access to financial services for Californians, particularly unbanked and underbanked populations.” In addition, PBLA and the California Public Banking Alliance (CPBA) advised Representatives Rashida Tlaib (D-MI) and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-NY) on the 2023 reintroduction of the Public Banking Act, a federal bill that aims to facilitate the establishment of public banks by states and local governments.

Another example is the Illinois Climate Bank. In 2021, the Illinois Climate and Equitable Jobs Act (CEJA) established the Illinois Finance Authority as the Climate Bank. Within 12 months, the bank distributed $265 million in private capital, with 65 percent going to disadvantaged communities to support green initiatives.

The people of Massachusetts are also pushing for a public bank to benefit small businesses and community development. The Massachusetts Public Banking coalition is a statewide group spearheading the effort to establish a public bank in the state. The current legislation, H 975/S 632, builds on the work of longtime advocates for economic opportunity, including the late Mel King.

According to The Boston Foundation’s Boston Indicators, the capital access gap for business owners of color alone is $574 million each year. The Massachusetts Public Bank intends to close the gap by targeting underbanked groups as its main beneficiaries. It focuses on women- and minority-owned businesses, gateway cities, small- and medium-sized farms, coastal communities, affordable housing projects, and climate infrastructure projects.

In addition, the Massachusetts Public Bank would seek to partner with existing banks in the community. Following North Dakota’s model, the mandate for the Massachusetts bank is that it “shall seek to complement and support the operating of” banks in the state. As Massachusetts Public Banking states, “The primary ways this partnership manifests are through participation loans that expand the capacity of existing banks and a limited scope of mission that aims to supplement rather than supplant existing financing opportunities while being responsive to the banking sector’s needs.”

The Pushback Continues

However, the push for public banking is not without pushback—particularly from conservatives and capitalists who want to preserve the status quo. Echoes of this opposition can be heard in the narrative from the Cato Institute of what supposedly happens when “the government owns the banks [and] lending decisions become increasingly driven by politics rather than economics.” The institute also claimed, “Government-owned banks also tend to underprice risk in order to appeal to voters.”

The question to ask ourselves is whether this so-called “underpricing of risk” is that at all. Instead, it reflects the willingness of public banks to introduce relationship banking to people of color and the businesses they own that, otherwise, are systematically excluded from a biased banking system that thrives on credit scores and other subjective measures. As we saw with Silicon Valley Bank, the failure of private banks to plan for risk also costs taxpayers.

Changing the Financial Rules

If we act as if we can close the racial wealth gap with the current banking system, progress will be minimal, at best.As public banks gain footing, financial innovation will facilitate the flow of capital from various sources to underbanked sectors, especially entrepreneurs and consumers of color. One example is Runway, a firm committed to dismantling systemic barriers and reimagining financial policies and practices. The nonprofit seeks to advance resiliency for Black-owned businesses and the communities they serve by building emergent financial practices and infrastructure that close the racial wealth gap for good. In partnership with investors, financial institutions, and the entrepreneurial ecosystem, Runway collaborates as an innovative means to bridge the old economy of extraction to the next economy based on relationship and community regeneration.

Others are also looking at ways to close the wealth gap through increased capital flows, such as to people of color who want to become business owners. For example, the Rockefeller Foundation’s Zero Gap Fund (ZGF) invests in two enterprises—Apis & Heritage Capital Partners (A&H) based in Oakland, CA, and Founders First Capital Partners based in San Diego. These investments are meant to advance racial equity and economic justice through innovative financial tools.

Within this new ecosystem, public banks will be willing partners. We need look no further than the Bank of North Dakota, which established the model of how to address unmet needs in financing while also supporting existing financial institutions. Similarly, the proposed Massachusetts Public Bank aims to work with local financial institutions to “strengthen our local communities, help preserve local businesses, foster new businesses, and create jobs across the state.”

One thing is clear: bankers can’t do the same thing over and again and expect a different result. If we act as if we can close the racial wealth gap with the current banking system, progress will be minimal, at best.

Only by introducing more public banks in states across the United States will capital finally flow to diverse communities in support of individuals, households, and businesses of color. The result will be greater economic opportunity, job creation, and friendly competition that entices banks in all communities to pursue partnerships to explore untapped opportunities.