Editors’ note: This article is based on the experiences of two organizations that were in desperate straits. It tells the story, from the perspective of the executives, of what it took to turn the ships so that they were headed back in the right direction. They may not be all the way back in safe port, but who is these days? The circumstances that led to the organizations’ turning point had many elements that were unique to each one. The fact that they took such similar actions provides useful insights.

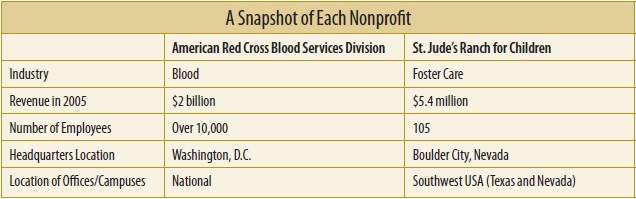

The year was 2006. Two large and important nonprofit organizations faced desperate situations. St. Jude’s Ranch for Children had run through all of its unrestricted reserves and was losing $826,000 a year. The chairman of the board of directors believed they had three months before they would have to declare bankruptcy and close their doors. At the American Red Cross, about two-thirds of the revenues came from the Blood Services Division. In 2005, the Blood Services Division lost approximately $300 million, which caused the Red Cross to run a deficit of more than $100 million. Given its unique charter, the Red Cross was not in danger of going bankrupt, but it was in serious jeopardy of losing its independence as a nonprofit organization and coming under much stricter government oversight.

The financial losses were only one example of the troubles plaguing these two organizations. For example, Christine Spadafor, who would become the new CEO of St. Jude’s Ranch, recalls an employee telling her that he had accumulated several hundred hours of comp time. “Everyone kept track of his or her own hours,” Christine recalled, “and if they worked an extra hour or two one day, they believed they had earned comp time, which they could (and did) use whenever they wanted without notifying their supervisor.”

Today, both of these organizations are financially healthy and providing higher-quality services to their clients. St. Jude’s Ranch has been voted one of the top five charities in Nevada and the ninth best place to work in that state, and the Red Cross Blood Services Division has dramatically improved its operations, as demonstrated by the following metrics:

- 70 percent reduction in laboratory testing issues;

- 52 percent reduction in recalls; and

- 63 percent reduction in storage, shipping, and return issues.

In describing the changes that occurred within the two organizations, we do not want to imply that all their problems were solved; but what happened certainly changed their trajectories and positioned them for sustainability. Jack McGuire, the former CEO of the Blood Services Division, draws an analogy of driving down the road and discovering that you have made a wrong turn. Turning the car around does not mean you will reach your destination, but at least you will now be headed in the right direction. Because both organizations took actions that were surprisingly similar, we believe there are important insights and lessons to share. Both U-turns were difficult and painful. The boards and the senior management teams took dramatic actions in order to change the way the organizations did business. We will focus on the five key areas where both followed a similar script: new leadership; board actions; hiring and firing; financial issues; and cultural change.

Methodology

The primary source of information for this article was interviews. Our research began when we wrote a Harvard Business School–style case study about St. Jude’s Ranch for Children, now taught in the MBA program at the Tuck School of Business. In the course of writing the case, visiting the site, reading through hundreds of pages of documents, and interviewing the key participants, we felt there were important milestones and insights. For the American Red Cross portion of this article, we relied on Jack McGuire, who served as head of the Blood Services Division and also served, for a couple of years, as acting director of the American Red Cross. Jack participated in several in-depth interviews and numerous follow-up discussions. We did not have access to internal Red Cross documents but were able to gain additional supporting information from articles, annual reports, and other public information.

The Problems at the Blood Services Division of the American Red Cross

In 2006, the Blood Services Division was the nation’s largest supplier of blood and blood products, providing about half of the blood used in medical procedures in the United States. In addition to its financial problems, the Blood Services Division was operating under a consent decree with the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), requiring that it fix its problems or its leadership would be jailed.

The Blood Services Division was decentralized and inefficient. It was organized geographically, with each region allowed to set its own prices and sell blood anywhere in the United States. So, if pricing were higher in a different part of the country, one division would sell blood to another division rather than serve the hospitals in its region. Being organized regionally also meant that the Blood Services Division could not take full advantage of economies of scale.

A careful analysis of the Blood Services Division revealed that each region actually operated eight different businesses. For instance, although all the businesses involved blood, collecting blood is a very different business from selling hemoglobin. Each business served different customers, competed with different companies, and was governed by different regulatory agencies. When the Blood Services Division ran into financial problems, rather than focusing on the losses in any particular product line it tried to increase blood prices by 20 to 25 percent. The result was angry customers, reduced market share, and increasing losses.

The Problems at St. Jude’s Ranch for Children

St. Jude’s Ranch for Children is a nonprofit that provides therapeutic residential foster care and related community services. It transforms the lives of abused, at-risk children and homeless young adults and families. St. Jude’s Ranch provides a safe, homelike environment on its three campuses—where children are nurtured, learn life skills, and heal from traumas they have encountered—as well as community homeless and sibling preservation programs. In 2006, in addition to its financial problems, St. Jude’s Ranch faced numerous organizational and operational issues. For example, the State of Texas revoked the contract of one of St. Jude’s facilities and stopped referring new children.

New Leadership

As is typical in many turnaround situations, the first step both boards took was to install new leadership. In hiring a new CEO, both the Blood Services Division and St. Jude’s Ranch selected people who had the same characteristics in three important respects:

- Technical knowledge of the industry;

- Significant experience working with nonprofit organizations; and

- Personal resources.

The American Red Cross hired Jack McGuire as its new CEO for the Blood Services Division. Jack had extensive knowledge of the healthcare sector and the blood industry from his work at Johnson & Johnson and several start-ups. The Blood Services Division had even been his customer at one point, when it purchased his company’s medical devices to help manage its blood supply.

Jack’s background also included serving on the board of a number of nonprofit organizations. His work with nonprofits gave him credibility with the staff at the Red Cross and also made him sensitive to the cultural difference between nonprofit and for-profit organizations—he did not try to turn the Blood Services Division into a clone of a Johnson & Johnson business unit but instead focused on leveraging experience gained from the for-profit world that could benefit the nonprofit world.

Christine Spadafor had extensive experience working with the Boston courts as a pro bono attorney, representing neglected/abused children. Although she had limited experience with foster care, she had direct experience working with the government on public health issues when she was at the U.S. Department of Labor and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. In addition to possessing a Harvard law degree, Christine was a registered nurse, had a master’s degree from the Harvard School of Public Health, and had been the general counsel of a children’s hospital as well as CEO of a mental health facility.

Like Jack, Christine had served on several nonprofit boards, including a biomedical research organization and a nonprofit serving critically ill children and their families. Both Jack and Christine had also previously been involved with organizations that had undergone a turnaround, and so knew what to expect.

Interestingly, neither one was dependent on their new organization to build their career or make money. Jack was nearing retirement and had sufficient financial resources to do so. During the turnaround at the Blood Services Division, he risked getting fired on several occasions because he refused to waver from his team’s vision and plan. “It was much easier to hold firm and ‘walk the talk,’ ” Jack admitted, “knowing that my family and I were financially secure and not dependent on this job.”

Similarly, Christine had been a partner at the Boston Consulting Group and two other international consulting companies, and had established her own successful consulting company. Because she cared about St. Jude’s Ranch and the children it served, she was determined to do what it took to turn it around. But she was confident that if the board did not like what she was doing and fired her, she could go back to running her company.

As CEOs during a turnaround, Christine and Jack aggregated unusual power and responsibility. Most nonprofits make important (and often unimportant) decisions in a collaborative way with lengthy discussions, but during the turnaround, when it came to issues like hiring and firing, Jack and Christine often made unilateral decisions. Similarly, they did their own analysis of what was wrong and what had to change. While both were careful to stay within the vision they had worked out with their boards, they will admit to having been the primary, if not the sole, strategist in setting a new direction.

Some differences between Jack’s and Christine’s approaches are noteworthy. Jack stressed the importance of being consistent in the message sent to employees, board members, and stakeholders. He knew he was making progress when an FDA commissioner reported that people from every region of the Blood Services Division recited the same six corporate objectives when asked about changes being made in the organization. As Jack saw it, “the CEO’s job is to clearly envision what the new organization needs to look like and then consistently sell it to everyone around him time after time.”

Christine, on the other hand, placed a premium on establishing credibility and stability. As soon as she started, she focused on recertifying the lagging Texas campus with the state foster care system. By achieving this early victory, she gained not only credibility but also momentum, and she gave an early signal of how the new organization would be different.

Board Actions

The boards played a critical role in both situations. The first step was recognizing the full nature and extent of the problem, something most nonprofit (and for-profit) boards tend to underestimate until it is too late. Generally, boards are unwilling or unable to take the drastic steps required. For St. Jude’s Ranch, the wake-up call came when they realized they would be bankrupt in three months. Before she became the CEO, Christine was hired as a consultant to do an organizational assessment. She knew the national board was ready for bold action when they unanimously accepted and fully supported implementation of all the recommendations in her report.

Increasing financial losses, the loss of some major customers, and the worsening relationship with the FDA were the impetus for the Blood Services Division. In desperate times, boards often make the mistake of hiring a “savior” who promises to solve all their problems. These two boards wisely chose experienced leaders who understood that executing a successful turnaround would be demanding, painful, and time consuming. Most importantly, they gave their new CEOs their full support and the freedom to run the organization in a new way.

Finally, both boards had to be fully engaged during the turnarounds. Board attendance and involvement were spotty, especially at St. Jude’s Ranch. To get board members more involved, both Jack and Christine organized board retreats, where they reaffirmed the mission, began a discussion of the new vision, and developed concrete three-year strategic plans. They then updated and reinvigorated the board’s committee structures to foster greater engagement.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Hiring and Firing

Firing people is never a pleasant job, but it is critical in any turnaround. Christine told the national board of St. Jude’s Ranch, “Expect 100 percent turnover the first year, because we are raising the bar.” The actual rate was not that high, but it was substantial, especially with senior managers. Thankfully, some firings actually helped build morale and sent a clear message. When she discovered that one of the people who picked up donations from the Las Vegas casinos was keeping some of the items, Christine immediately fired the employee and transparently announced the reason at the next town hall meeting: “Stealing from the children is never tolerated at St. Jude’s Ranch.”

At the Blood Services Division, Jack also found two people acting unethically, and fired them. By the time firings and layoffs were completed, only two of the thirty-six top people were still with the division, and both had new roles. “When you need to lay off people at a nonprofit,” Jack reflected, “how you do it is very important. I tried to make decisions about who to let go in a completely objective, cold way but implemented it very warmly.” For both organizations, choosing the right people to lay off, and doing it in a transparent, logical way, was critical.

Turnover, firings, and layoffs gave both organizations the opportunity to hire new people with the right skill set and attitude. These hiring decisions were crucial. In some cases, both Jack and Christine found people inside the organization they could promote to fill the new positions. At times, both made mistakes. “The key,” said Christine, “is to recognize your mistake immediately and correct it”—as she did when she terminated a new CFO within months of his having been hired.

Financial Issues

Faced with dire financial circumstances, the boards and senior management at both organizations developed short-term and long-term financial plans. Both organizations resisted the temptation to look for a “silver bullet” or make dramatic cuts in their expenses in order to balance the budget. Instead, they developed business plans designed to put the organization on solid long-term footing while at the same time figuring out ways to get through the immediate crisis.

At St. Jude’s Ranch, most of the operating expenses are related to personnel. Regulatory requirements about child-to-staff ratios, plus the needs of the children, make it very difficult to cut staff. Therefore, operating expenses, even during the first year of the turnaround, went up by about $300,000. The only major line item that was cut was fundraising, which had become bloated and ineffective. On the other hand, new leadership uncovered some great opportunities to increase revenues. By increasing occupancy, St. Jude’s Ranch added $400,000 of revenue in program service fees from state agencies. By doing better-focused fundraising, St. Jude’s Ranch increased contributions by $300,000, grants by $78,000, and special events receipts by $50,000.

But the biggest improvement on the revenue side came from in-kind donations. “As our reputation in the community improved, St. Jude’s Ranch was able to apply for more grants, especially in-kind grants,” explained Christine. “We applied for and won a $1 million extreme makeover from HomeAid of Southern Nevada. As part of this in-kind donation, the contractor, Pardee Homes, transformed the dilapidated buildings and dirt yards at the Boulder City campus into attractive buildings with grass yards.” Christine recalls a wide-eyed child asking, “Are we allowed to walk on the grass?”

Although St. Jude’s Ranch has run a surplus every year since fiscal year 2007, it is still highly dependent on grants and contributions. Each year it sets targets for each area of fundraising, closely monitors the grants, and works hard at communicating with donors. Senior staff and the board are also determined to build a more sustainable business model that is less dependent on grants and donations. Early on, Christine realized that reimbursement from the State of Nevada and the State of Texas only covered about half the cost of residential foster care, even when St. Jude’s Ranch had relatively full occupancy. With the current budget problems in these states, it is unlikely that they will increase the reimbursement rate, even if St. Jude’s Ranch provides compelling evidence of being underfunded. So, the staff and board are looking to build or acquire additional, complementary services related to their mission that might be profitable and will reduce their dependence on donations.

The key to the financial turnaround at the Blood Services Division of the American Red Cross was the realization that it was involved in eight distinct businesses. For example, its main business was collecting, processing, and then selling blood to hospitals for transfusions. This business represented about 80 percent of the Blood Services Division’s revenue. The Red Cross was the dominant player in this business, and its competition was mostly other nonprofit organizations. But the Blood Services Division also collected blood and separated out hemoglobin (and other proteins), which it sold to the pharmaceutical branches of hospitals. In this second business, the Blood Services Division competed with companies like Bristol-Myers Squibb, which used its economies of scale, its distribution network, and the latest equipment to gain market share.

A careful cost analysis convinced senior management that six of the eight businesses would never be profitable, and that hospitals were being well served by the existing competition. The deficit of $300 million faced by the Blood Services Division provided the impetus to make changes. Over the next year and a half, the Blood Services Division sold off the six unprofitable businesses. It kept the blood transfusion business and one other specialized business related to reagents. The second business will probably continue to run a small deficit, but since no one else provides this service, the Red Cross believes it should.

By selling off six businesses, the Blood Services Division not only reduced its losses but also was better able to concentrate on its core business of supplying hospitals with blood for transfusions. As a result, within eighteen months the Blood Services Division was generating a positive cash flow.

Implementing Cultural Change

Improving the financial performance of both organizations played an important role in transforming the organizations’ culture, which both Christine and Jack considered their greatest challenge. As Jack observed, “By focusing attention on the financial problems, we created a real sense of urgency and a clear message that things had to change.”

Saint Jude’s Ranch needed to develop a culture with a much higher degree of transparency, professionalism, and accountability. Financial accountability provided a good starting point. Senior management made sure that everyone fully understood the organization’s dire financial condition. Staff members also received updates about operational and financial metrics linked to the three-year strategic plan at monthly town hall meetings conducted by Christine.

To change the culture of St. Jude’s Ranch, senior management created and tracked metrics that clearly demonstrated how the organization was doing. St. Jude’s Ranch tracked overall measures like “For every $1 donated, 88 cents go directly to our children.” And it tracked smaller metrics like “Was a receipt and thank you sent within forty-eight hours of receiving a gift?” One of the first new hires in 2006 was a human resources director, who created job descriptions, personnel policies, and an annual evaluation process, providing structure, fairness, and accountability. Most importantly, senior management continually reinforced the ways in which this heightened accountability benefited the children.

The existing culture at the Blood Services Division was one of serving and helping. Employees were attracted to the Red Cross because of a desire to work for an organization that saved lives. As a disaster relief organization, people were used to acting first and hoping that donations would be sufficient to cover the costs. It was also a decentralized organization in which each local chapter had a great deal of autonomy in the way it did business.

To transform the culture, senior management needed to get everyone focused on the same set of goals. “My job was to take the plan and sell it,” Jack explained. “I needed to be more than a manager. I needed to be a cheerleader, a coach, and a good listener.” In transforming the culture, senior management made sure everyone understood and “shared” the problem. The most important question that helped transform the organization was not “What should we do?” but “What happens if we cease to exist?” The idea that the Blood Services Division might fold and that people would no longer have access to an adequate blood supply was a powerful motivator. It got employees to think about revenues and expenses and do business differently.

Conclusion to the Two Tales

The story of these two organizations carries important lessons. Faced with a desperate turnaround situation, many organizations become overwhelmed and do not know where to begin. These two organizations narrowed their focus to five essential areas: new leadership, board actions, hiring and firing, financial issues, and cultural change. In so doing, St. Jude’s Ranch and the Blood Services Division of the American Red Cross climbed out of a deep hole and survived.

Both organizations continue to face major challenges. For St. Jude’s Ranch, the challenge is to create a sustainable business plan that is less dependent on donations and limited state reimbursement. The Blood Services Division continues to operate under a consent decree with the FDA. In a press release issued on June 17, 2010, the FDA wrote: “Since 2003, the American Red Cross has made progress addressing some of its quality issues, including standardizing procedures, upgrading its National Testing Laboratories, and increasing oversight of the organization. However, to fully comply with federal regulations and consent decree provisions, the American Red Cross must make swift, additional progress on all of the issues the FDA has identified.” Developing a customized and highly sophisticated software system is one of a number of these complicated challenges.

In advising an organization trying to dig its way out of trouble, Jack’s advice is “be consistent.” When an organization is reeling, it is especially difficult and terribly important for the leader to be consistent in his or her message and actions. Christine is a strong believer in engaging the entire organization to collectively achieve and measure outcomes. She strongly advises all organizations, but particularly those going through a turnaround, that “the system that analyzes areas for improvement must equally measure success.” To measure outcomes requires gathering objective data, which, in a time of crisis, can seem like a poor use of resources. However, without targets and the data to measure progress, it is impossible to change the culture or know if you are achieving your strategic goals and successfully transforming the organization.

Putting These Stories in Context

Nonprofit turnarounds have become a hot topic. Most of the literature we read about turnarounds was based on specific case studies. It generally emphasized the importance of improving, reinvigorating, or even re-creating the board of directors. In many instances, especially with those organizations that declared bankruptcy, the board played an even more significant and hands-on role than was the case with the Blood Services Division or St. Jude’s Ranch. The literature is clear: the board must recognize when a turnaround is needed, and then fully support the tough decisions that have to be made by the executive leadership.

Another common feature of the literature is the importance of having the organization’s leadership deal directly with customers and midlevel managers. (Jack traveled the country to deliver his message about how the Red Cross Blood Services Division was changing.) Finally, all the literature stressed the importance of reevaluating the strategy of the organization in light of the mission and core values. Many organizations did something similar to what Christine did at St. Jude’s Ranch, and held an offsite retreat for the board where they reaffirmed their mission and developed strategies.

In two respects, our article provides a different perspective from what we found in the literature. First, in selecting turnaround leaders, both organizations selected people who did not need the job financially nor were looking to build a career. Second, our article clearly articulates the fact that even a successful turnaround in which the organization’s culture improves and its financial condition becomes stable does not fully insulate the organization from its past. Turning around a nonprofit is always a work in progress.

John H. Vogel Jr. is adjunct professor at the Tuck School of Business at Dartmouth; Kelly L. Winquist is a current MPA candidate at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government; and Christine J. Spadafor is CEO of St. Jude’s Ranch for Children, in Boulder City, Nevada.

To comment on this article, write to us at feedback@npqmag.org. Order reprints from https://store.dev-npq-site.pantheonsite.io, using code 190208.