This article is the fourth article in our series—The Promise of Targeted Universalism: Community Leaders Respond—that NPQ is publishing in partnership with the national racial and economic justice nonprofit Prosperity Now. In this series, writers will examine how targeted universalism—a narrative framework that advocates the use of targeted approaches to achieve universal goals—can inform efforts to close the racial wealth gap, community by community.

In 1994, a group of business, nonprofit, and philanthropic leaders came together to form the Enterprise Corporation of the Delta, a loan fund created to improve lives in 55 opportunity-starved counties in the tristate Mississippi Delta region. Today the organization, now known as HOPE, is a full-service financial institution and policy institute that expanded to cover five Deep South states (Alabama, Arkansas, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Tennessee) and still embodies the principles upon which it was founded. One of us (Bill Bynum) was the organization’s founding CEO. The other (Ed Sivak), joined in 2001 and serves as chief policy and communications officer.

At HOPE, financial services are our primary tool for ensuring that factors such as race, gender, and geography do not limit one’s ability to support one’s families and communities. Roughly half of people who have a checking account, home mortgage, or business loan with HOPE were previously unbanked or underbanked. Many had relied on high-cost, often predatory, financial service providers. From the beginning, our efforts to achieve a society where everyone has access to basic banking services.

As john a. powell and his colleagues put it, targeted universalism involves “setting universal goals pursued by targeted processes to achieve those goals…. The strategies developed to achieve those goals are targeted, based upon how different groups are situated within structures, culture, and across geographies to obtain the universal goal.”[1] The concept of “targeted universalism” may be of recent origin, but our work has long been geared towards the ideas embraced by that theory.

Setting the Stage: Understanding the Gaps in Financial Service Access

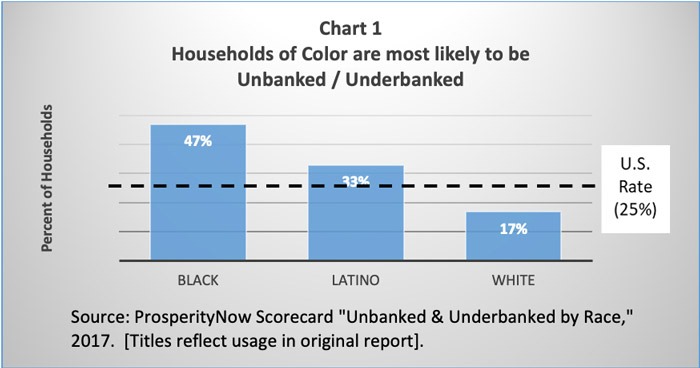

Targeted universalism aspires to establish universal goals and then design targeted approaches to realize those goals. And one cannot understand targeted approaches without a deep appreciation for the communities we serve. In 2020, HOPE made 5,910 loans totaling $160.4 million. At HOPE, 81 percent of our members are Black or Latinx, 74 percent have incomes below $50,000, and 59 percent of our members are women.[2] Chart 1 offers national data that illustrates the enormous gaps in simple access to banking services that remain between white, Latinx, and Black borrowers.

Banking status is vital to building wealth, stabilizing households, and fortifying families against financial headwinds. Low-income families that are banked are more likely to own wealth-building assets (such as homes and businesses) than those who are unbanked.[3] Even with very low balances, the presence of savings can play a major economic security role. Just $250 may be the difference between encountering an eviction or utility shutoff; or being protected from one. Likewise, children from low-income families with savings accounts experience higher college enrollment and graduation rates, relative to families of similar means without savings accounts.[4]

When it comes to buying homes, one out of four Black mortgage applicants and nearly one out of five Latinx applicants have their loan applications denied. For white borrowers, this figure is just 14 percent.[5] In Mississippi, Black mortgage applicants earning over $150,000 a year have their applications denied at a higher rate than white applicants earning between $30,000 and $50,000.[6] Beyond the obvious wealth-building aspects, homeownership has been shown to contribute to better health outcomes,[7] reduced high school dropout rates, and increased civic participation.[8]

Similar patterns persist in small business lending. Only 13 percent of Black-owned and 20 percent of Latinx-owned businesses reported receiving the full share of financing requested from banks, compared to 40 percent for white-owned firms. Not surprisingly, Black firms cited lack of credit access as “the single most important challenge firms expect to face as a result of the pandemic” at a rate 2.5 times higher than for white firms.[9] The disparities are particularly disturbing given the evidence that business ownership both reduces poverty and narrows the racial wealth gap.[10]

Targeting the Response to Address Systemic Gaps

In the US, affluent people rely on private bankers as financial problem-solvers. But few people of color and people with lower incomes have this luxury. HOPE places a priority on being the private banker for those who languish in banking deserts across the Deep South.

Closing banking gaps requires being accessible. Of HOPE’s 24 branches, 20 are located in majority Black counties or parishes, and seven are in rural communities with fewer than 10,000 people. The median poverty rate in our communities is 33 percent, and in many places, HOPE is the only depository with a local branch. HOPE’s staff, management and governance also reflect a commitment to the people and places we serve. Roughly 68 percent of HOPE’s employees are people of color and 72 percent are women. Sixty percent of management positions are filled by people of color and 62 percent by women. The majority of HOPE’s board members are people of color.

Access is also created by offering products and services designed to mitigate the social, economic, and systemic barriers facing those we serve. With Black family wealth being one tenth of white family wealth,[11] Black households must overcome the absence of available cash. In response, HOPE structures programs that offer assistance with down-payments, covers closing costs, and finances up to 100 percent of the home value.

Access is also achieved through the credit decision-making process. Bias within automated underwriting algorithms, particularly for mortgage loans, is well documented.[12] While algorithms speed decision-making, the efficiencies are drawn from data that reflect ongoing discrimination, as well as the long period when housing discrimination was codified in law.

Given the limitations of automated underwriting, HOPE manually underwrites every mortgage. During the review process, special consideration is given to medical debt, which falls disproportionately on people of color.[13] HOPE considers non-traditional sources of credit information—such as rent, utility, and mobile phone payment histories—in lieu of traditional credit scores. For those who are not yet ready to take on a mortgage, HOPE offers credit-building products and financial advisory services. This approach enables HOPE to originate over 80 percent of its mortgages to people of color, over five times the rate of other Mississippi banks and credit unions.

All of these strategies are anchored in on-the-ground feedback and data. HOPE takes seriously its accountability to the credit union’s member-owners. The members elect directors and serve on local advisory councils that inform product and service design and outreach strategy. Through the HOPE Community Partnership, HOPE works with local stakeholders to identify community priorities and develop strategic plans for improving local conditions. For example, residents of Drew, Mississippi, population 1,927, used this forum to develop plans to repurpose an abandoned armory to expand access to healthy, nutritious food. As a result, the facility has been converted into a food distribution center with cold storage that also provides health screenings, nutrition education, cooking classes, meal planning, and budgeting. In other communities, new affordable housing, parks, lighting projects, and murals are some of the projects that came to fruition through this process.

CDFIs—a Targeted Approach to Achieving Universal Access to Finance

Far too often, the financial sector views people of color as liabilities to be managed rather than assets to be developed. Large gaps in financial service access, persisting over generations, bear out the consequences of government and private sector policies and practices that perpetuate this outcome.

As COVID-19 upended lives and the economy, it quickly became clear that federal responses like the US Small Business Administration Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) were not designed to meet the needs of Black, Indigenous, and other business owners of color. Not only did PPP rely on traditional banks as the delivery system, but sole proprietorships, which account for more than 90 percent of all Black businesses were ineligible in the program’s initial phase.[14] These structural inequities devastated already undercapitalized entrepreneurs of color, and they suffered an initial closure rate of 40 percent compared to 17 percent for white-owned businesses as a result.[15]

HOPE was one of several community development financial institutions (CDFIs) and minority financial institutions (MFIs) that stepped into the breach,[16] successfully advocating to open the program to sole proprietors, and processing 5,216 PPP loans—89 percent of which went to borrowers of color and 50 percent to women. The average amount of these forgivable loans was a modest $26,814, over $40,000 less than the program average nationwide.[17]

The PPP experience, combined with ongoing economic and social justice upheaval, have prompted federal policy makers to make unprecedented funding available to equip CDFIs and MFIs to fill gaps in the banking system. This year, HOPE was among hundreds of such institutions that shared $1.75 billion in grants from the CDFI Fund. And we are awaiting decisions on the distribution of $9 billion in equity from the Emergency Capital Investment Program, administered by the Treasury Department. The outsized contributions of CDFIs and MFIs to an inclusive recovery underscores the importance of increased and targeted investment by banks, private industry, philanthropy, and government to fortify this vital segment of the financial system.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

At the same time, along with increased resources and opportunities, come new levels of complexity. As CDFIs and MFIs position themselves to deploy exponentially more capital, they must be steadfast in prioritizing a commitment to community development, over the countervailing forces of maximizing efficiencies and profit that characterize traditional banks. Similarly, investors must be circumspect in making their decisions. Because, just as the billions of dollars in capital flowing into this sector has the potential to dramatically close opportunity gaps, the reverse is also true. Evidence of this can be found in Mississippi, the state with the most CDFIs in the nation—a status achieved when community banks in the state tapped into record amounts of federal CDFI funding after the 2008 financial crisis. However, a 2021 analysis showed that the rate of mortgage lending to Black borrowers by CDFI banks in Mississippi is less than 13 percent, lower than the 17 percent rate of all mortgage lenders that report Home Mortgage Disclosure Act data—in a state where the Black population is nearly 40 percent.[18]

As people of color become America’s emerging majority, universal banking is in the nation’s collective interest. A recent McKinsey study found that closing the racial wealth gap could increase US gross domestic product (GDP) between $1 and $1.5 trillion by 2028.[19] Sustained and targeted investment in CDFIs and MFIs with demonstrated a commitment to serving people of color is a proven solution for setting the nation on a path toward inclusive economic prosperity.

Notes

[1] john a. powell, Stephen Menendian, and Wendy Ake, Targeted Universalism, Policy & Practice, Haas Institute for a Fair and Inclusive Society, University of California, Berkeley, May 2019. Quote on page 5

[2] HOPE, From Moments to a Movement: 2020 Impact Report, 2021.

[3] Jeanne M. Hogarth and Kevin H. O’ Donnell, “Banking Relationships of Lower-Income Families and the Governmental Trend toward Electronic Payment,” Federal Reserve Bulletin (July 1999): 459–73.

[4] Signe-Mary McKernan, Caroline Ratcliffe, Breno Braga, Emma Cancian Kalish, “Thriving Residents, Thriving Cities: Family Financial Security Matters for Cities,” Urban Institute (April 2016). Ezra Levin. “Children’s Savings Accounts Expand Opportunity,” Prosperity Now (January 2014).

[5] PolicyMap, Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council (FFIEC): Home Mortgage Disclosure Act (HMDA) Summaries. “Percent of Home Loan Applications from Black / Hispanic / Non- Hispanic White Applicants That Were Denied.” (2019).

[6] “2019 State of Mississippi Analysis of Impediments to Fair Housing Choice.” (Dec. 31, 2019). Table VI.7, page 135.

[7] Sims et al. “Importance of Housing and Cardiovascular Health and Well-Being: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association.” Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes. Vol 13, Issue 8. 2020.

[8] William J. Bynum, Diana Elliott, Edward Sivak, “Opening Mobility Pathways by Closing the Financial Services Gap,” US Partnership on Mobility from Poverty.” (February 2018).

[9] “Small Business Credit Survey. 2021 Report on Employer Firms,” Federal Reserve Banks of Atlanta, Boston, Chicago, Cleveland, Dallas, Kansas City, Minneapolis, New York, Philadelphia, Richmond, St. Louis, San Francisco

[10]“Income Patching among Microentrepreneurs,” Field Trendline Series, Issue 4 (Aspen, CO: Aspen Institute, 2013). Association for Enterprise Opportunity, The Tapestry of Black Business Ownership in America, March 2019.

[11] McIntosh, Kriston, Emily Moss, Ryan Nunn and Jay Shambaugh. Examining the Black-white wealth gap. Brookings Institution. February 2020.

[12] James A. Allen, “The Color of Algorithms: An Analysis and Proposed Research Agenda for Deterring Algorithmic Redlining,” 46 Fordham Urb. L.J. 219 (2019).

[13] Neil Bennett, Jonathan Eggleston, Laryssa Mykta and Briana Sullivan, “Who Had Medical Debt in the United States?.” US Census Bureau (April 2021).

[14] Perry, Andre M. Tynesia Boyeaa-Robinson and Carl Romer. How Black-owned businesses can make the most out of the Biden infrastructure plan. Brookings Institution. April 2021.

[15] Fairlie, Robert W. “The Impact of COVID-19 on Small Business Owners: Evidence of Early-Stage Losses From The April 2020 Current Population Survey.” National Bureau of Economic Research. w27309.pdf (nber.org). June 2020.

[16] HOPE, From Moments to a Movement: 2020 Impact Report, 2021.

[17] Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) Report: Approvals through 05/31/2021 (sba.gov)

[18] Testimony of William J. (Bill) Bynum before the United States Senate Committee on Banking, Housing and Urban Affairs. “An Economy that Works For Everyone: Investing in Rural Communities.” Senate-Banking-Committee-Bynum-Written-Testimony-042021.pdf (hopepolicy.org) April, 2021.

[19] The economic impact of closing the racial wealth gap | McKinsey August 2019.