January 13, 2020; New York Times

There seems to be a government obsession with the idea that poor people, especially adults who partake of programs like SNAP, are slackers just looking for a handout. The best way our current leadership has to address this, to move people off welfare, is to cut their benefits and require them to work. The economy is booming and unemployment is low, so jobs should be plentiful. What’s the problem?

From the moment this was proposed (and written about by NPQ and others), the nonprofit community has girded itself for a spike in demand. The state of West Virginia has been a proving ground for the folly of this government theory.

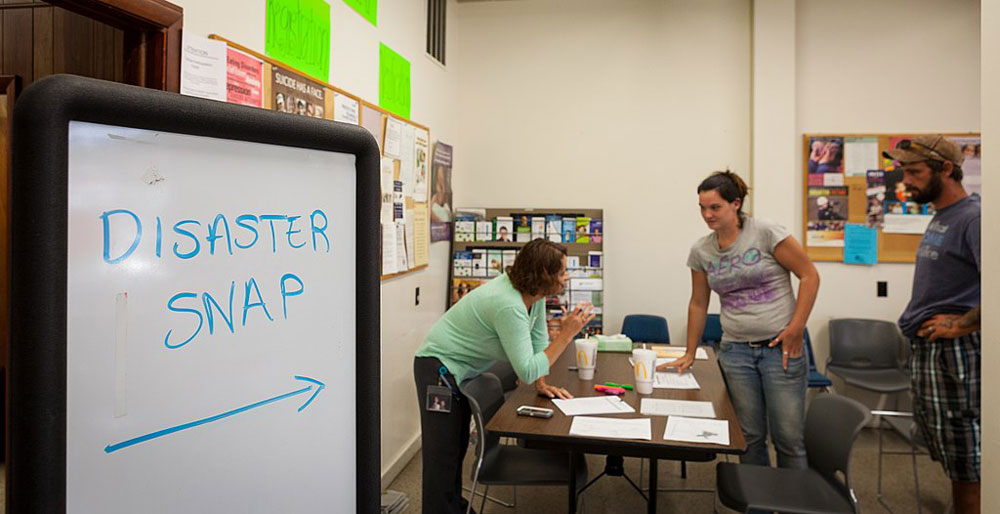

Four years ago, nine counties in West Virginia were caught in a state policy change that demanded proof of work or 20 hours a week of training in order for people to receive food stamps on a consistent basis. As of this April, this policy will apply to all “able-bodied adults without dependents” across the country. As logical and simple as it sounds, when you walk in the shoes of those “able-bodied adults,” a different story emerges—one that’s neither simple, logical, or kind, but speaks to the inequity of the governmental perspective on what it is like to live and work in poverty.

The lives of SNAP recipients often feature daily battles with issues of health or care of family members, with unreliable transportation, erratic work hours (at the whim of hourly employment without regular schedules), and unpredictable living arrangements. Without SNAP, the impact is well known among the nonprofits and faith-based organizations that run food pantries and homeless shelters. West Virginia can attest to this; food banks that used to have slow periods are now busy all the time. Soup kitchen numbers have risen and remained high with no sign of dropping.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Researchers say that changing the work requirement has had no impact on the job market. The West Virginia Center on Budget and Policy, a research group that focuses on social safety-net issues, found little change in the job market in the three years after its implementation. While 5,410 people lost SNAP benefits across those nine counties, the growth in workforce lagged behind there, even as it doubled in the rest of West Virginia. “We can prove it from the data that this does not work,” said Seth DiStefano, policy outreach director at the Center.

While the state Department of Health and Human Resources initially agreed, saying, “Our best data does not indicate that the program has had a significant impact on employment figures,” it later reworded the statement perhaps in hopes of thinly obscuring the policy’s failure. An email message to Campbell Robertson of the New York Times last week from a department spokesperson stated the available data “does not paint a clear picture of the impact” of the changes on employment in the nine counties.

Lawmakers in West Virginia may be bound and determined to see the policy as a winning proposition simply because it fits a common, if senseless, narrative. One of the sponsors of the 2018 bill that restored the work requirement statewide, Tom Fast, considers the law a total policy success due to “significant savings overall” and a low unemployment rate. His attitude to the barriers to work faced by many in the population hit hardest by this law is, “If a person just chooses not to work, which those are the people that were targeted, they’re not going to get a free ride.” Of people who are face concrete obstacles to steady work, like a lack of transportation, he added, “If there’s a will, there’s a way.”

The lure of a strong narrative that paints “others” as lazy and unmotivated is tried and true in this country, despite any facts to the contrary. Meanwhile, the nonprofit sector must address the aftermath. For poor people, food insecurity is never too far away. And when it is seen as a “bootstraps” issue, a matter of moral fortitude one just has to deal with, many will fall.—Carole Levine