July 17, 2016; Al Jazeera

The high profile “honor killing” of controversial Pakistani social media celebrity Qandeel Baloch once again aims the spotlight at violence toward women in Pakistan and the advocates fighting against it and the culture that supports it. Baloch was drugged and then strangled by her brother Wazeem Azeem last week because he believed his sister had “dishonored his family” with her contentious Internet personality and posting provocative pictures of herself.

Born Fauzia Azeem, Baloch grew up in the Punjab region of Northeastern Pakistan, where she also died at her parents’ home. Azeem had her own version of homegrown celebrity when she launched a social media enterprise and posted videos that went viral. Juxtaposed with Pakistan’s conservative culture, Baloch’s outspoken personality and daring wardrobe choices made her an easy target—not only for the public, but her family as well. Even after her death, Baloch’s social media pages are filled with misogynistic comments, some arguing she had it coming.

In many ways, Baloch’s public persona and candid profiles were alien to her Pakistani counterparts. While Pakistan is a country where divorce is largely unpracticed and considered to be taboo, Baloch was divorced with a child. Parents still arrange marriages for their children, but Baloch openly talked about sex.

“I am trying to change the typical orthodox mindset of people who don’t wanna come out of their shells of false beliefs and old practices,” wrote Baloch in her final Facebook post on July 4th.

Regardless of how one may feel about her life choices, Baloch was a tour-de-force in pushing the envelope for Pakistani women. “She was the most self-exposed person, and what was different about her is that she was from a poor background,” said Fasi Zaka, a radio host. “She did all this on her own. She is much more than Kim Kardashian; she went against the norms of society—and went on to do what she wanted, on her own terms.”

Women are statistically more likely to be the victims of honor crimes, wherein relatives (such as parents or spouse) kill the subject in the belief she dishonored the family. In Baloch’s case it was due to her online persona, but in other cases young women and girls have been killed for choosing to marry without permission or as the result of a domestic conflict, among other reasons.

According to the Human Rights Commission, there were almost 1,000 reported honor killings of women last year in Pakistan. The figure is believed to be higher due to underreporting, particularly in rural areas. There were also 90 incidents of acid attacks, 72 burnings, 344 rapes or gang rapes, and 268 reported sexual assaults and harassments of women.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Some see Baloch’s death, and honor killings in general, as an indictment of Pakistan’s barbaric response to individuals who defy its conservative culture. “She was killed because she said and did things that made people feel uncomfortable and angry,” said Erum Haider, a Ph.D. student at Georgetown University who is originally from Karachi. “We feel that there is no value to a woman’s life if she doesn’t live in a particular way…in the bounds of what a conservative, patriarchal society expects of you.”

Baloch’s brother voiced no regrets, though her parents are grief-stricken. “I am not embarrassed at all over what I did,” said her brother, whose attitude is common in Pakistan and other parts of the Asian and Middle Eastern world where predominantly conservative Muslim societies are fighting modern social mores.

“[In 2015] violence against women remained rampant as the most pervasive violation of their rights in the country,” wrote the Human Rights Commission (HRC) “Different initiatives taken at the public and private level to address the issue lacked consistency and thus did not yield any meaningful impact.”

Indeed, under Islamic Law in Pakistan, justice is often elusive in honor killings because a murder victim’s family can personally pardon the perpetrator even after they have been convicted of the crime. (Early this morning, the Pakistani government officially forbid the Baloch family from forgiving Azeem in this manner.) According to HRC, in several cases of violence toward women, the culprits are law enforcement officers. Three policemen were arrested for the gang rape of a woman in Nasirabad at the beginning of last year.

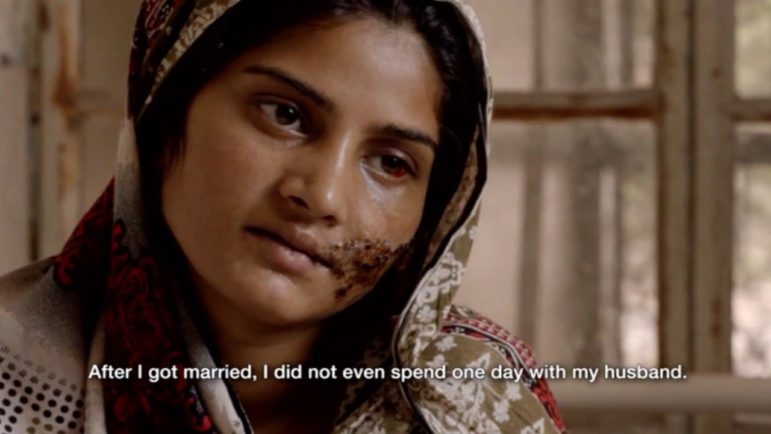

Sharmeen Obaid-Chinoy, the Pakistani filmmaker behind A Girl in the River: The Price of Forgiveness, the Oscar-award-winning documentary on honor killings, said she was disturbed by the story and called for renewed action.

I’m very shaken up today. Activists in Pakistan have been screaming hoarse about honor killings; it is an epidemic, it takes place not only in towns, but in major cities as well. What are we going to do as a nation?

According to Chinoy, the nation’s leaders must pass legislation condemning honor killings. “It’s upon the lawmakers to punish these people. We need to start making examples of people. It appears it is very easy to kill a woman in this country—and you can walk off scot-free.”—Shafaq Hasan